What Ukrainians, their politicians and experts think about the reintegration of occupied Donbas is broadly known. The latter two groups have free access to media spaces and are happy to use them, while the mood of ordinary Ukrainians is constantly tracked by sociologists. But when it comes to attitudes on the other side of the line of contact, that’s a question that’s much harder to answer. Rallies, flash mobs, group petitions and other public events take place in ORDiLO exclusively on orders from those in charge of the two pseudo-republics. In short, they are no indicator of anything.

When it comes to opinion polls, however, the situation is much more difficult in occupied Donbas. Not long ago, Serhiy Syvokho, an advisor to the NSC Secretary, confirmed that the Zelenskiy team had commissioned a survey of the voter mood in ORDiLO and that the president was confident in the reliability of the outcome of such a survey. Syvokho did not say what the numbers were or who carried out the survey, but that such a survey is taking place is no news. Despite everything going on there, pollsters, including Ukrainian and international ones, really do work in the occupied zone. The question is how much their results can be taken at face value. Probably not much, although not only political commentators but also officials who are responsible for formulating the government’s strategy towards the Donbas trust them.

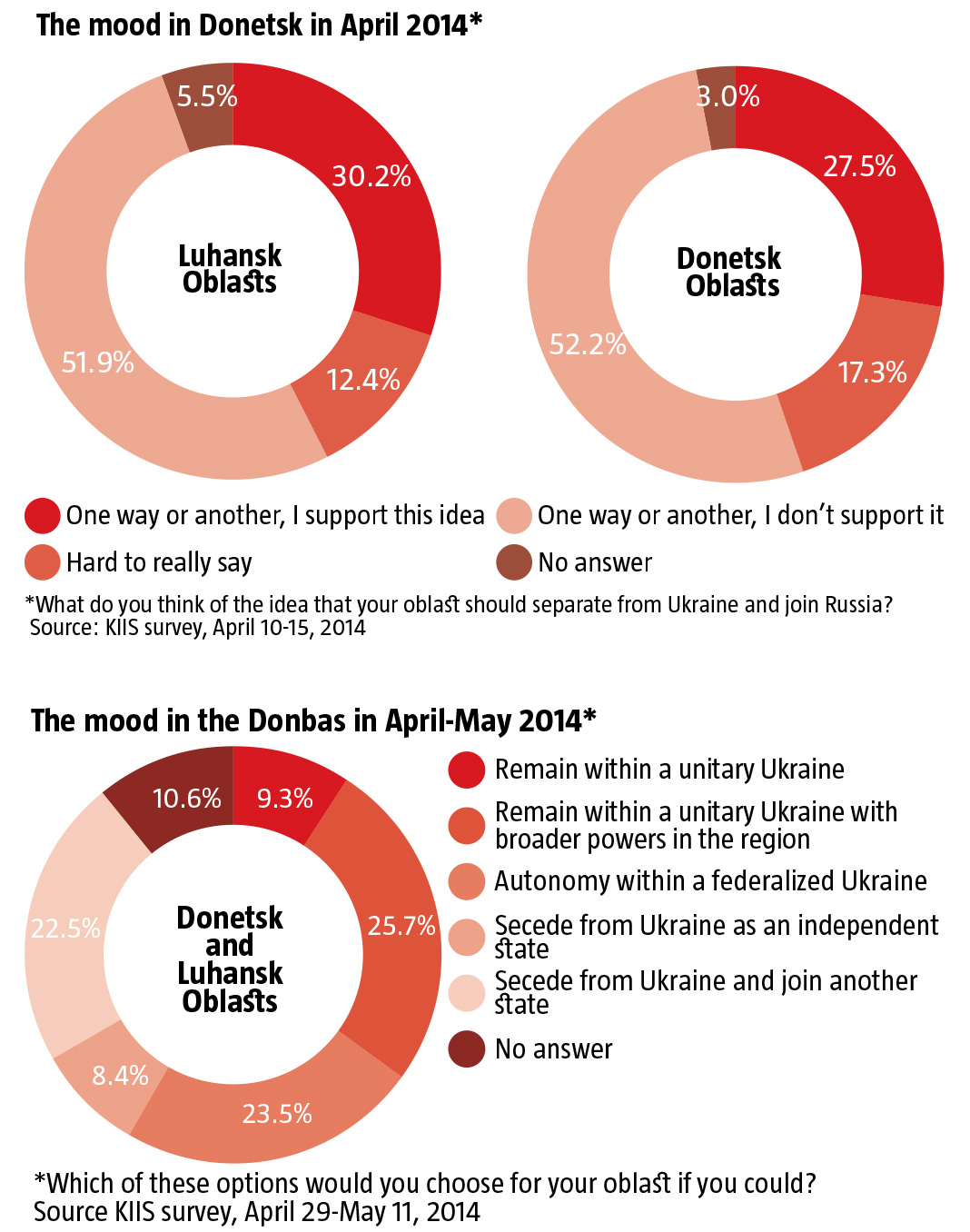

One of the last surveys to cover all of the Donbas was in April-May 2014, carried out by the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology. It showed that 8.4% supported independence for the region while 22.5% favored joining Russia (see The mood in the Donbas in April-May 2014). At the same time, KIIS undertook another survey that yielded similar results: 27.5% of residents in Donetsk Oblast supported joining Russia, while 30.3% of residents in Luhansk Oblast did (see The mood in Donetsk in April 2014). This shows that the separatists among locals in the Donbas represented less than one third of the population. Over 2015–2016, KIIS carried out some more surveys that partly or fully encompassed the occupied territories. The poll was done in the form of a personal interview, which is considered the most reliable. However, under the conditions at the time, it was also the most risky. Moreover, residents of the two “republics” were asked not just about their daily humanitarian needs but also what they thought of the situation in the Donbas, attitudes towards Ukrainian parties and politicians, about their confidence in social institutions and about whether they thought there was a war between Ukraine and Russia.

RELATED ARTICLE: The evolution of homo sovieticus

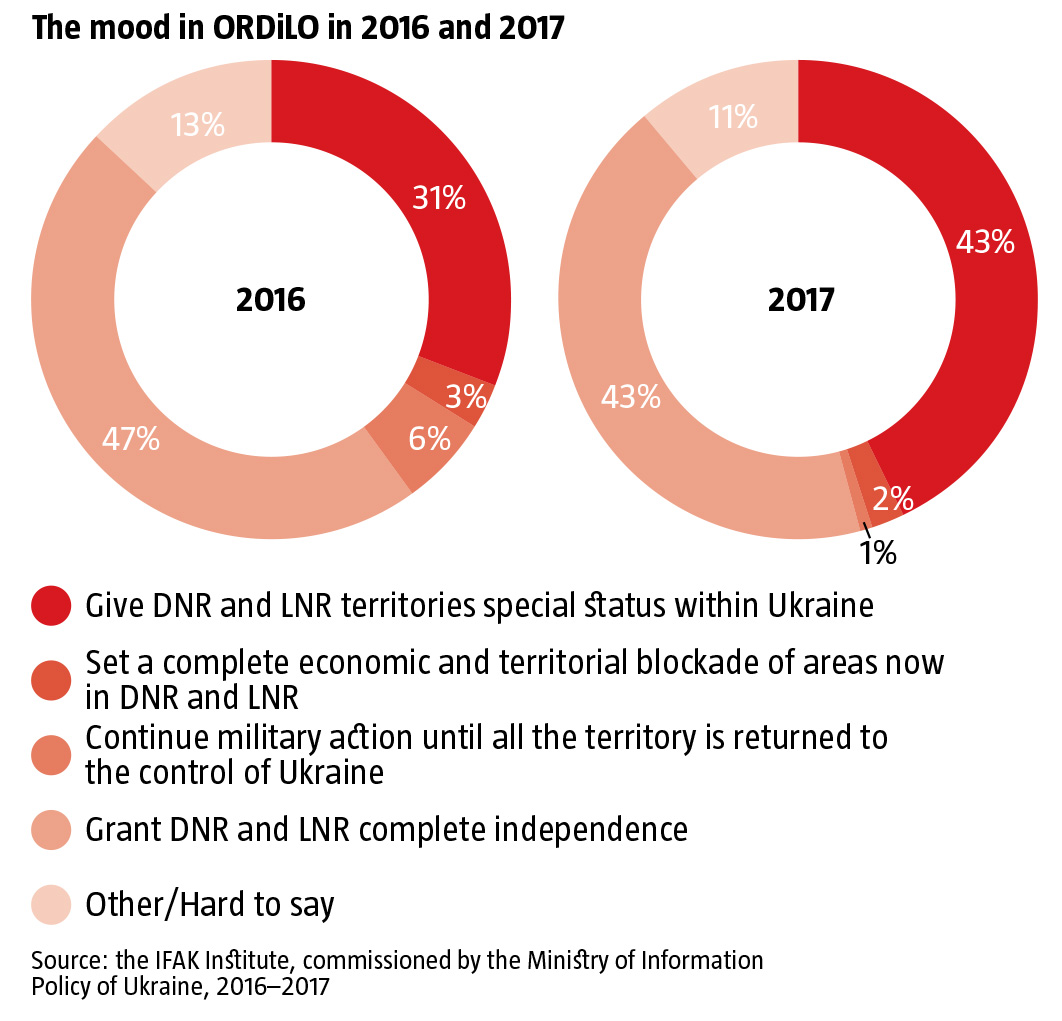

In 2016–2017, the Ministry of Information Policy also attempted to test the mood in ORDiLO, commissioning the IFAK International Research Agency. IFAK ran two polls in both the Ukrainian and Russian proxy side of the line of contact, also using personal interview methodology. The survey touched on a series of politically sensitive issues. According to the published results, in 2017, 43% of the residents of ORDiLO wanted to see their “republics” granted special status within Ukraine while the same proportion, 43% wanted the territory to become independent (see The mood in ORDiLO in 2016 and 2017). Unfortunately, the results of these two surveys raise serious doubts because of the company that carried them out. For instance, IFAK presented the option of returning ORDiLO to a unitary Ukraine, unlike the other options, exclusively by force. Moreover, among the options respondents were offered was “a complete economic and territorial blockade” of ORDiLO itself. This kind of questioning must be laid at the feet of the authors of the survey.

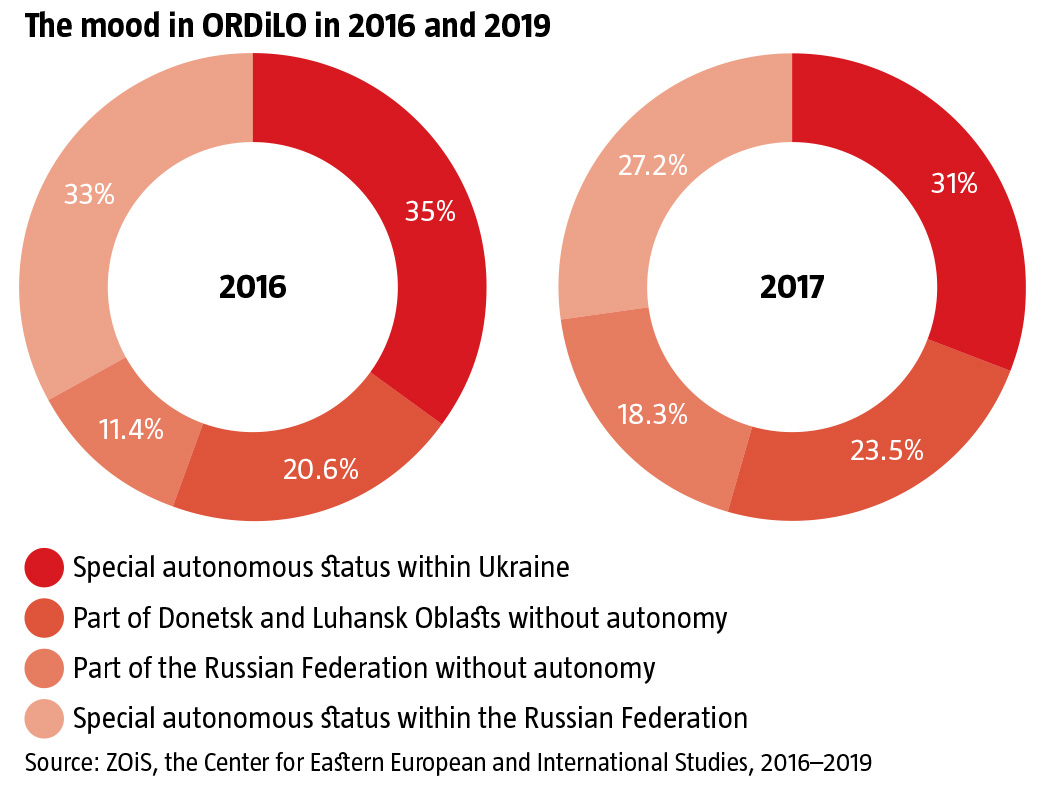

Among the opinion polls carried out in ORDiLO by international organizations, the best-known survey was the Center for Eastern European and International Studies, which ran two waves, in 2016 and 2019. The results for 2016 showed that 35% of ORDiLO residents supported the idea of returning to Ukraine as an autonomous entity, while 20.6% favored returning without autonomy. 33.1% wanted autonomy within Russia and another 11.4% wanted to join Russia without autonomy. There were no significant shifts in 2019: the share of those who wanted to return to Ukraine or Russia was 54.5% and 44.5%, compared to 55.5% and 44.5% in 2016 (see The mood in ORDiLO in 2016 and 2019). Still the surveys mentioned here are only a small fraction of the dozens of studies that have been carried out in the years of occupation –possibly even hundreds at this point. In short, Syvokho’s statements about the absence of numbers coming from the occupied territories should not be believed. In any case, there’s nothing extraordinary in these measurements. It’s another question entirely to what extent these results can be trusted.

Debate over the reliability and point of surveys in ORDiLO began to circulate in sociological circles in Ukraine back in 2014. One of the most open discussions among experts from top polling organizations in Ukraine took place in May 2015 at Shevchenko National University in Kyiv. Some researchers, including KIIS General Manager Volodymyr Paniotto, insisted on the purpose and feasibility of such surveys. Another group, including Democratic Initiative Fund (DIF) Director Iryna Bekeshkina, noted that there were methodological problems that would affect the quality of the results obtained.

In the first place, there were organizational issues for pollsters. In order to survey using personal interviews, a network of trained interviewers had to be in place locally, but this was often difficult because of ongoing military action. A necessary phase of a sociological study is quality control over the work of the interviewers, a selection process that typically involves telephone calls to potential respondents. Unfortunately, this is impossible to do under the circumstances. In short, cooperation with groups of interviewers in ORDiLO is based purely on trust. Meanwhile, the interviewers’ work presents serious risks to the lives of these individuals, because those who interview residents of the “republics” at the behest of a Ukrainian organization can very easily find themselves being interrogated in some basement. Given the spy-mania that has been cultivated by the occupying administration, this kind of outcome is entirely possible. How much this affects the quality of the research is impossible to determine.

Telephone interview methodology is far safer for both the interviewers and interviewees, as it is not done face-to-face. This is how the Center for Eastern European and International Studies undertook its survey. Marketing specialists actually prefer the low cost and convenience of telephone surveys, but professional sociologists are fairly critical of the method. Firstly, they require an abbreviated format and a slew of thematic restrictions. Talking to people over the phone about political views when the respondents are in the epicenter of a war and under foreign occupation is not the best approach. Secondly, the landline network is sharply in decline in an era of widespread mobile communications. In ORDiLO, especially in smaller towns and villages, such networks may have been simply destroyed or be out of commission altogether.

But what affects the results of such surveys far more is the state of the respondents themselves. Firstly, residents in the occupied territories are understandably much more suspicious because of fear for their own lives. As a February 2018 DIF survey illustrated, residents of ORDiLO with whom respondents were in contact generally avoided discussing anything political, especially over the phone. Nor is this surprising, given that the occupation administration has engaged in political persecution on a very wide scale since Day One. These “investigations” too often end up with show trials in a kangaroo court and severe sentences. Moreover, people haven’t forgotten the chaotic massacres of 2014-15, when thousands if not tens of thousands of locals found themselves being interrogated in basements or were killed outright for their “wrong” and “seditious” political positions.

At the same time, residents of ORDiLO are afraid of Ukraine as a result of relentless propaganda and scaremongering about the “secret prisons of the SBU” and “filtration camps” – the latter which are a modern Russian invention. And so, expecting natural trust towards strangers who present themselves as interviewers is quite pointless, even ridiculous. In practice, this distrust results in massive refusals to participate in surveys and insincere responses. Of course, the silence of a respondent can also speak volumes, but it’s rarely possible to interpret such silences unambiguously.

RELATED ARTICLE: Dead Souls: The people’s census

And so, it’s worth treating any sociological data from ORDiLO with caution, even if it has been collected by a reputable organization using the most reliable methodology. However, this doesn’t remove the need to study public opinion in the occupied territories. In a situation where hybrid warfare is being waged, not to mention the prospect of reintegrating ORDiLO, such information is definitely useful intelligence, but still unreliable, based on the circumstances under which it has been gained. Another point is that public opinion in the occupied territories has been distorted by severe pressure from propaganda compounded by informational isolation. That means that even the most honest responses will continue to be the responses of individuals who have been bombarded with disinformation, terrorized and turned against Ukraine.

In short, it makes no sense at all for Ukraine to base its policies towards the region or to develop strategies for deoccupying and reintegrating ORDiLO on the opinions of locals. In order to know what the people there really think, they first have to be liberated, from the physical and informational violence they have suffered under Russia’s proxies.

Translated by Lidia Wolanskyj

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook