Ukrainians are once again facing the question: what is the essence of Ukrainian identity? In other words, what characteristics can one use to understand whether an individual is Ukrainian. Are these conventional elements, such as language, traditions or symbols? Or are these elements no longer enough, especially after the Revolution of Dignity and the war in Eastern Ukraine have made other criteria important? Having some external characteristics is no longer sufficient. What defines Ukrainianness is how an individual perceives Ukraine, how he or she acts towards Ukraine and its citizens. Ukrainian identity should not be perceived as something homogenous. There are several concepts of what it means to be Ukrainian in society today, and they morph constantly. What are these transformations?

The question of Ukrainian identity has become especially important with the start of the war in Eastern Ukraine. Earlier, too, there were debates on whether Russian-speakers in Ukraine can be identified as Ukrainians, and what the pantheon of the Ukrainian nation’s heroes should look like. But they were often fed by politicians trying to use this for political dividends and a victory in yet another election. Overall, Ukrainian society had not been too concerned with identity as more pressing issues dominated the agenda. Russia’s aggression suddenly showed that “who are Ukrainians?” is a vital question. Who is one of your own, and who is not? Are Ukrainian Russian-speakers Russians, and do they entitle Russia to “protect” them? Is language the only factor of Ukrainianness?

Hrushevsky’s question

Ironically, Ukrainian society faced the same question exactly a century ago. In 1917, historian and statesman Mykhailo Hrushevsky published a bulletin titled “Who are Ukrainians and what they want” explaining the origins of Ukrainians, the essence of Ukrainian identity and the tasks of the national movement in the context of building new relations with Russia to the residents of Ukraine and the supporters of the Ukrainian movement. The declaration of independence in 1991 seemed to eliminate Hrushevsky’s question. But the Revolution of Dignity and the war in the Donbas showed that Ukrainians need to seek an answer once again. This answer may define the future of Ukraine.

A correct answer can only come from a correct question. This means looking at the concepts of personal and collective identity separately. Identity is oneness, similarity of two objects. The Polish language defines it with the word tożsamość, or sameness. It has travelled into Ukrainian as tozhsamist. In personal identity, the individual is the two objects in different timeframes. In other words, personal identity ensures awareness of its continuity and answers the following question: am I of today the same person as I was several years ago? This identity enables us to change and be aware of that change while preserving our integrity.

RELATED ARTICLE: The problem with Irish

Collective identity helps recognize similarity with other people and build a social group with them. We are similar, so we are a group. Collective identity thus covers two processes. Firstly, an individual has to be aware of his or her similarity with a certain group of people. Secondly, this individual has to act as a “typical representative” of this group to confirm that he or she is part of it. Importantly, this “typical representative” is a stereotype, a concept of what a member of the group should be. A discussion of Ukrainian identity is thus about collective identity, i.e. the awareness of belonging to a certain social group. An individual can have many collective identities, including national, religious, professional, family and more. Sometimes they clash and affect personal identity. For instance, a neophyte will build a completely new identity after conversion, so some collective identities important in the past will be replaced by others.

Ethnic nation vs political nation

How do individuals become aware of belonging to a certain nation? Obviously, they need some criteria on which basis they can say that they have certain characteristics, therefore they belong to a certain nation. Overall, these characteristics fall into two groups based on the type of nations – ethnicor culturaland politicalor territorial models of national identity. The key characteristics of ethnic or cultural identity are ethnic. This includes culture and origin. An individual proves his or her national identity through the language of a certain ethnic group, the knowledge of its culture, and the respective ethnic origin. The key characteristics of a political nation include civil loyalty to a national state. An individual with a certain citizenship can be considered representative of a certain nation.

For a long time, these two models have been perceived as polar and mutually excluding. They were even linked with two nations in Europe. German identity classically qualified as the ethnic model, while French identity was perceived as political. There was no unified German state between the late 18th and early 19th centuries, but the Germans were aware of their national identity because they belonged to one culture. By contrast, the French Revolution ultimately shaped the unitary French state, with French citizenship as the criterion of Frenchness regardless of the individual’s ethnic origin. The French and the German models spread to other countries. Nation building in Central and Eastern Europe mostly followed the German model, while Western Europe followed the French one. Apart from France, Switzerland is often mentioned as a model of a country with four official languages and one national identity. But the next wave of historical research revealed that purely political nations do not exist because they are always rooted in an ethnic nation. Switzerland was initially exclusively comprised of German-speaking cantons. French- and Italian-speaking ones joined later. The Swiss identity had built on ethnic foundation before it transformed into a political nation. The nation France built was, too, far from political. Just recall the struggle against patois, the local dialects which one literary French language had to replace. Up until the early 20th century, a belief was strong in France that only someone of French ethnic origin and Catholic faith could be truly French. This triggered a discussion about the two Frances of a political and an ethnic nation.

Acquire or win?

Another counterproductive element of contrasting ethnic and political models of a nation is its failure to take into account an individual’s proactiveness aimed at acquiring or confirming their national identity. Criteria, such as ethnic origin or citizenship, are antagonists to this model. None of them comes through proactiveness: an individual receives ethnic origin without taking any effort to that end. Citizenship mostly follows the same pattern as something given at birth. Moreover, these two criteria can merge because there is no logical contradiction between them. One can perfectly demand the issuance of citizenship to individuals of “proper” ethnic origin. In some cases, obtaining citizenship means integrating with an ethnic culture. The procedure of acquiring citizenship in the US provides a good illustration with its requirements, such as the knowledge of English and American history.

Another situation is possible where ethnic and political criteria of identity intertwine. For example, an individual learns a language intentionally because he or she believes that it’s impossible to be a decent citizen without it. Or an individual has a proactive civic position in addition to merely remembering his or her citizenship. In both cases, individuals have to demonstrate their proactiveness in order to confirm their national identity. Whether this proactiveness refers to ethnic or political component is less relevant.

How does an individual obtain identity? Does this happen effortlessly and unintentionally? Is identity a product of intentional choice and activity? Sociology uses two terms, ascriptive and acquired, to define these polar notions. Ascriptive is a social status obtained regardless of personal will and activity. Sex is an ascriptive feature as we are born with a certain sex. Acquired are characteristics that require will or certain actions. The difference between them is quite obscure. An ascriptive feature can become acquired, and an acquired one can turn ascriptive with time. But this distinction helps better understand the Ukrainian situation.

Ascriptive characteristics of its identity include the following ones:

1) being born in Ukraine;

2) having Ukrainian citizenship;

3) living most of one’s life in Ukraine; and

4) being Ukrainian by nationality.

Acquired characteristics are as follows:

1) respecting Ukrainian laws and form of government;

2) identifying oneself as Ukrainian;

3) feeling responsible for Ukraine; and

4) being a Christian believer.

Both groups include ethnic and political components.

An attentive reader will note that that the list does not include the knowledge of Ukrainian. This feature can be both ascriptive and acquired. For someone raised in a Ukrainian-speaking environment the knowledge of Ukrainian is an ascriptive feature as the learning was not an intentional choice. For someone raised in an environment speaking a different language, the knowledge of Ukrainian is a result of intentional activity, i.e. an acquired feature.

Types of Ukrainian identity

For now, these look like hypotheses. But sociologists have been studying identity in Ukraine since the declaration of independence in 1991. In a slew of surveys, respondents were asked to rank certain criteria of being Ukrainian by importance. The list described above is from a nationwide survey of 2006 held by the Sociology Institute of the National Academy of Sciences in Ukraine. Similar methodology was used in 2013 and 2015 studies by the Region, Nation and Beyond project by the University of St. Gallen in Switzerland.

I have used mutlidimensional statistical analysis to explore that the characteristics of identity fall into two big categories that fit within ascriptive/acquired rather than ethnic/political. This pattern shows in the data from 2006, 2013 and 2015.

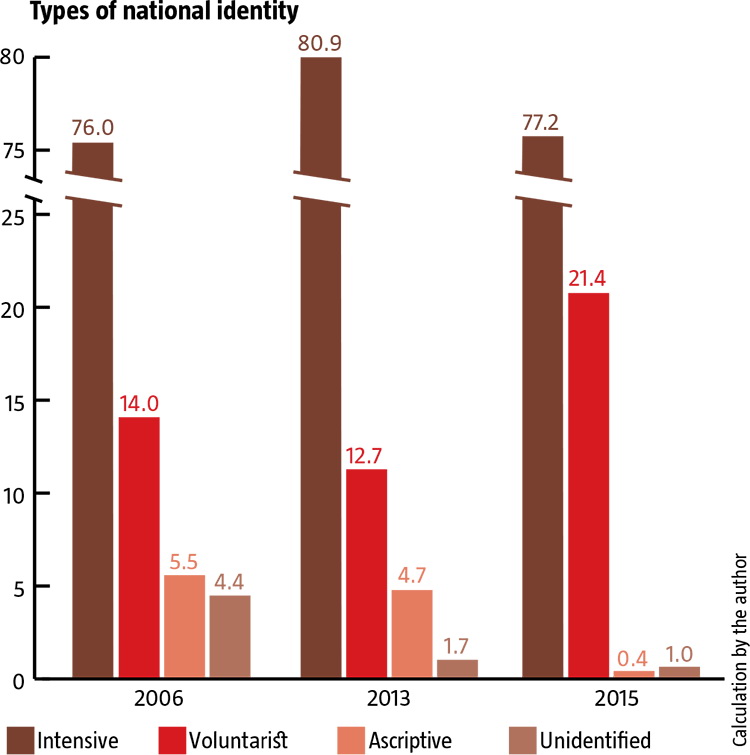

Yet, there are more types of identity. Apparently, two pure types exist where an individual identifies as Ukrainian based solely on ascriptive or acquired characteristics. We can refer to them as ascriptive and voluntarist. Where there are pure types, there are mixed types as well. This is when both ascriptive and acquired characteristics matter for an individual. This type can be referred to as intensive because it sets the highest requirements for representation of a nation. A fourth type is possible, where respondents list criteria that are important for someone identifying themselves as Ukrainian, even though they personally identify themselves as the Ukrainians (see Types of national identity).

The data from 2006-2015 allows for a number of conclusions. Firstly, the intenstive type of identity dominates in Ukraine. At least 75% of those polled in Ukraine believe that both ascriptive and acquired criteria define Ukrainianness. Secondly, the share of the voluntarist type has increased from 14% to 21% since the Maidan and the start of the war, stealing primarily from ascriptive identity. The latter’s share has plummeted from 5.5% to 0.4%. The unidentified group has shrunk from 4.4% to 1%.

Importantly, the survey did not take into account Crimea and the occupied parts of Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts. Therefore, one should compare the 2015 data with any other data set with great caution. The easiest thing to do is to exclude respondents from Crimea, Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts collected before 2014. That will reveal that the share of intensive identity type has hardly changed, while the share of voluntarist type will go from 12.6% to 20.7%. The greatest growth is from 10.5% in 2013 to 53.7% in 2015 in Zaporizhzhia Oblast from 21.1% to 44.5% in Odesa Oblast . The voluntarist group also grows by stealing from the intensive identity type.

This leads us to the third important conclusion. The Revolution of Dignity and the war have pushed a part of Ukrainians to reconsider their identity. Acquired characteristics grow more important to them while the role of ascriptive ones declines. This means that their definition of Ukrainian identity is based on the individual’s actions with regard to their country rather than on the possession of certain characteristics. Changes in the frontline regions illustrate this. In addition to Zaporizhzhia Oblast, the share of voluntarist group has grown in Kharkiv and Dnipro oblasts from 17.2% to 27.5% and from 14% to 23.1% respectively.

RELATED ARTICLE: The roadmap of demography

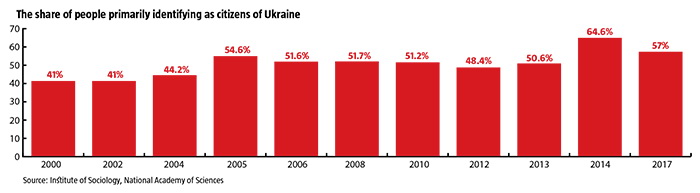

Why did the 2013-14 developments have to trigger the change in identity awareness? On its own, collective identity is not an objective, but an intersubjective phenomenon. It exists only because a large number of people believe that others are also aware that this identity exists. It’s this shared belief in phenomena or processes that makes them real in a social sense, i.e. with a realistic impact. How does this affect Ukrainian identity? Strengthening a sense of identity requires collective events showing to people that their group exists. For Ukrainians, such events are the Orange Revolution and the Revolution of Dignity. These social movements have made the Ukrainian nation visible. Monitoring of Ukrainian society from the National Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Sociology since 1992 shows the following trend between 2000 and 2017 (see The share of people primarily identifying as citizens of Ukraine).

Until 2005, the share of respondents primarily identifying themselves as citizens of Ukraine had been below 50%. It grew to 54.6% in 2005 and did not plunge to the pre-Orange Revolution level after that. The next leap came in 2014 when the share of those primarily identifying themselves as citizens of Ukraine grew to 64.6%. This went down to 57% by 2017. Still, it is higher than the pre-Revolution of Dignity figure. Both revolutions have thus boosted the share of people identifying primarily as citizens of Ukraine.

To sum this up, we can suggest that Ukrainian identity is undergoing slow change as acquired criteria play an increasingly greater role. As a result, Ukrainianness is no longer a characteristic perceived as given. It is increasingly seen as a result of conscious action and proactive civic position. Ethnic criteria remain important but are becoming secondary.

Danylo Sudyn, PhD in Sociology, Associate Professor of Sociology at the Ukrainian Catholic University

Translated by Anna Korbut

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook