The special operation had been prepared for a long time, probably throughout all years of Ukrainian independence, though not necessarily under the “Russian Spring” title. The name was ripped off from the Arab Spring, a series of mass protests, revolutions and military conflicts in several Arab countries. But it was ripped off for a reason. The Kremlin needed an analogy: the people supposedly organising themselves and rebelling against dictatorial regimes – in this case, the "Kiev junta".

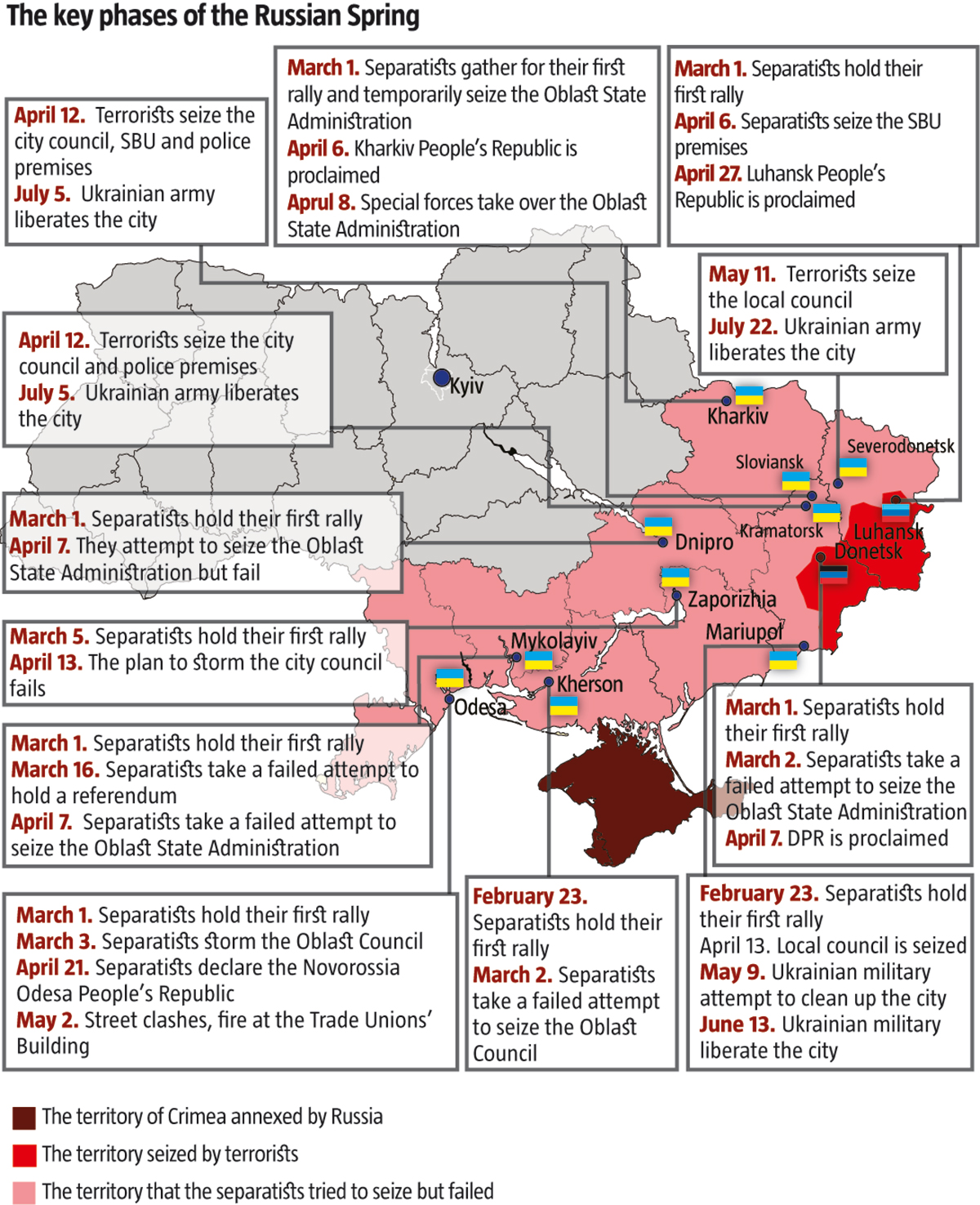

The hasty steps (that eventually led to the partial failure of the Russian Spring in Ukraine) help explain that its start was evidently planned for a later time. The ground was not sufficiently prepared and much was chaotic. Apparently, the Kremlin decided to launch it after Yanukovych's flight to Kharkiv and his failed attempts to arrange a separatist convention there. The operation began in different ways in different places. This indicated the absence of an established structured network which would operate under an elaborate scheme and be managed from a single centre. While the Crimean phase proceeded smoothly, with pro-Kremlin activists setting up the first roadblocks in Sevastopol alongside the police as soon as February 22, the rent-a-mobs organised in most cities of south-eastern Ukraine were of a more spontaneous nature.

Crimea fell first. The list of reasons that helped the operation succeed there starts with the ratification of the Kharkiv Agreements in 2010 that prolonged the stay of Russia’s Black Fleet there. This Russian contingent made up the basis for covert operations in 2014. The Russian Cossacks and other crowds were brought in for effect – an imitation of a popular revolt that had to look as convincing as possible. The management and coordination of all this was done by regular Russian officers. By February 23, the Ukrainian authorities had virtually no control over Sevastopol. Four days later, a Russian special forces team seized the Crimean Parliament and Council of Ministers buildings in Simferopol, while Crimean deputies announced a referendum on the status of the peninsula. Originally scheduled for May 25, it was later brought forward to March 30, then all the way to March 16. On March 1, the "little green men" started to block the bases of the Ukrainian Armed Forces.

RELATED ARTICLE: How trading with the occupied parts of the Donbas works as a loophole from paying taxes

A poor copy of the Crimean scenario

The mainland Ukraine saw a different scenario. Eight of its oblasts were targeted as easy prey, or so the Kremlin strategists presumed. Almost simultaneously with the developments in Crimea, ralliesbroke out in Kharkiv, Odesa, Luhansk, Donetsk, Kherson, Dnipro, Zaporizhia, Mykolayiv and many smaller towns. These also saw pro-Kremlin rallies, Russian flags, attempts to seize the Security Bureau of Ukraine or police premises and proclaim People's Republics – in some places more successfully than in others. However, the rebels did not gain the mass support that the organisers were very obviously banking on, and they often had to bring in "guest protesters" from Russia to try to turn the tide.

When the failure of the Russian Spring in south-eastern Ukraine became evident, the mass introduction of trained, armed saboteurs from Russia could save the operation. The places where they were deployed saw a completely different scenario to those that they did not reach. The proximity of the porous border with Russia in Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts partially secured the success of the Russian Spring there. Weapons, ammunition and subversive groups found their way into Ukraine through the unmonitored parts of the border. This would have been impossible without the support of the Border Service of the Russian FSB: they provided the terrorists with the necessary information and assistance, and refused to mutually close a number of border checkpoints in violation of agreements with the Ukrainian Border Guard. As a result, in May and June alone there were more than 20 cases of aggression against Ukrainian Border Guard units. Subsequently, it de facto lost control of an enormous section of the border from Krasna Talivka in Luhansk Oblast all the way to the Azov Sea coast.

The convenient proximity of the border is not the only reason why the Kremlin focused special attention on the Donbas. Over the 20th century, the region experienced at least two waves of de-Ukrainisation: the Holodomor famine and the mass settlement of Russians and criminals from around the Soviet Union who took part in the construction of factories and industrial plants. Most of those who came to build a brighter future stayed for good, and a territory that was Ukrainian-speaking in the 1920s and '30s gradually changed.

RELATED ARTICLE: The first steps of the Russian Spring in the Donbas: The surrender of the Luhansk SBU

In April 2014, the pro-Ukrainian citizens of Donetsk managed to take the fight to pro-Russian titushky, the infamous paid thugs used to attack protesters alongside the police, for one last time, but the sides were uneven. This was a standoff between peaceful people and young men equipped with baseball bats and metal bars, combined with the complete inactivity of the police. Then weapons began to flow into Donetsk and seizures of government buildings began. The concentration of Russian or pro-Russian diversionists like Alexandr Borodai or Andrey Purgin increased rapidly. The group led by Igor Girkin aka Strelkov, a Russian army veteran, seized Sloviansk. Then the cancer of separatism began to spread around the Donbas.

On the off chance

The idea of the “Donetsk People's Republic” had been bandied about in the Donbas for a long time. The DPR tricolourbanner was first spotted in 2006. At that time, a campaign was held to collect signatures of those who opposed what was branded "nationalist" policies of Viktor Yushchenko, the post-Orange Revolution president of Ukraine. The signatories demanded to make the Russian language an official state one and threatened seceding from Ukraine unless that demand was fulfilled. In 2010, a protest took place in Donetsk under the Russian flag and slogans of "Fascism will not pass".

Why then Russia and its contractors failed to implement their wide-ranging plans for the East of Ukraine? Especially as its agents here were telling the Kremlin for decades that the majority of south-eastern oblasts would queue for Russian passports as soon as the signal came from Moscow.

Firstly, it looks like Russia’s security experts and their colleagues elsewhere overestimated their own resources and the capabilities of their agents. The latter were taking Russian money and pledging loyalty to the empire, but that did not equal faithful service to it. It was just one of the ways to freeload on grants that even fans of Putin and Tsar Nicholas II like.

RELATED ARTICLE: Persecution of religions minorities in the Donbas

Secondly, the campaign was poorly coordinated. This could be due to the multi-faceted approach of the Russian masterminds to their Ukrainian contractors. The main work was conducted by official Russian representatives in Ukraine, including through their cultural institutions located in Kyiv, Odesa, Kharkiv, Lviv and Crimea. In addition to their representative and cultural functions, these institutions performed many more specialised ones, bringing together and coordinating the activities of pro-Russian organisations, cultivating them and using them as a tool of influence.

Thirdly, the political and business links played their role. The political leverage was concentrated in the hands of the Communist Party functionaries and the ruling Party of Regions. The business one was firmly linked to the Russian owners or co-owners of large Ukrainian enterprises. All these seamlessly acted in concert, complementing each other and working for a common idea. When the time came, however, this cooperation did not give the desired result: the fact that these networks were poorly coordinated, disabled by infighting and permeated with fringe figures like one-time small entrepreneur Pavel Gubarev or the infamously anti-Ukrainian Party of Regions member Arsen Klinchayev damaged their efficiency.

A model region

Another region that experience destabilisation attempts was Kherson Oblast that borders on Crimea in southern Ukraine. The mechanism used there did not differ greatly from those applied in other south-eastern oblasts. On February 22, local Euromaidan activists knocked down the Lenin monument on Freedom Square, and the following day, pro-Russian activists arranged a counter-demonstration that ended in mass clashes. By evening, pro-Ukrainian self-defense managed to bring the situation under control and secure the Oblast State Administration building. On March 1 did local fans of the Communist Party, Public Safety Committee, Ukrainian Choice (an organization led by Viktor Medvedchuk, a pro-Russian politician and a close ally of Vladimir Putin) and othersgathered again under the banner of the Russian Spring. They destroyed the monument to the Heavenly Hundred, the protesters shot on the Maidan, and urged Russian President Putin to send in his troops to Ukraine. Clashes were avoided on that day, but the next day the ranks of the local Russophiles were joined by guests from the Crimea. At that point, all of pro-Ukrainian Kherson came out to defend the Administration premises. This was virtually the last attempt by pro-Kremlin forces to knock the city off-balance as the Ukrainian security services intervened soon. According to their data, the chief curators of this campaign (apart from the Moscow-based strategists led by Putin’s aide Vladislav Surkov) were agents based both in the Russian Consulate General in Odesa and on the ground in Kherson. The consulate's resources were insufficient for rapid mobilisation. It did have several seemingly powerful structures under its wing, including the Russian Cultural Centre, a regional branch of the Russian Movement of Ukraine NGO, the Russian National Community – Rus NGO, the Centre of Russian Culture, the Ukrainian-Russian Charity Foundation and local branches of Russian Unity and Ukrainian Choice, as well as the low-profile local New Slavic Generation, Dolphin Sports Club and For a Healthy Lifestyle. However, they were not the force capable of pulling of a coup and taking over the entire region. Moreover, some of their leaders immediately switched to the pro-Ukrainian camp as soon as everything went pear-shaped, so that their names would not be associated with the separatists.

All of the above outfits, as well as Komitet Grazhdanskoy Bezopasnosti (Public Safety Committee), Saint George Union of Kherson and Kherson Triglav Slavic Native Faith religious community, as well as the events they were involved in, were funded from various sources and often not directly from Russia. The tell-tale signs of pro-Russian actors can be seen among the main sponsors and intermediaries. Above all, the oligarch Konstiantyn Grigorishin, whose Energostandart financial and industrial group has considerable economic interest and influence in the region. Grigorishin was a long-time sponsor of the Ukrainian Communist Party and, according to Ukrainian intelligence, his Energostandart is under the watchful eye of the FSB's Foreign Intelligence Service, which indicates direct accountability to Putin. Politician and oligarch Vadim Novinsky is similar. He also has considerable business interests in Kherson Oblast. In third place is old guard Bolshevik enforcer Kateryna Samoilyk (former Communist Party MP), who is accused of occasionally funding separatist protests. It is unlikely that she did this from her own savings, although that is how the legend has it. Given the Ukrainian Communist Party's close links with both Grigorishin and the Russian Communist Party, we can assume that Kateryna was only a link in a larger chain. Her rallies managed to attract as many as up to 250 supporters. The names of local pro-Russian Communist and Party of Regions deputies crop up among the immediate perpetrators of those rallies. Their task was to organise and realise propaganda, protests, violent clashes, flash mobs and a referendum.

RELATED ARTICLE: How propaganda on the war in Donbas worked through fiction literature

There are many reasons why they failed to take Kherson by force: from the erroneous confidence that the local population is pro-Russian to the lack of resources amongst the local Russophiles. Many supposedly pro-Russian organisations that were well publicised and had money thrown at them came up with zilch. Their membership was not enough to rouse the city to action, never mind seize important strategic objects and hold them until Putin’s troops arrive. The situation in Zaporizhia and Mykolaiv was almost identical. There was no chance of destabilising Dnipro either. Especially after the appointment of Ihor Kolomoiskyi as Head of the Oblast State Administration, who, alongside his partners, had a very creative approach to stopping the terrorist infection. Volunteer units were formed and armed, roadblocks were set up on entry roads into the city and a hunt for separatists was announced (the reward offered for detaining them and seizing their weapons had its effect). Equal assistance was provided to neighbouring regions.

The situation was somewhat more problematic in Odesa, where the tragic fire at the Trade Unions’ Building happened on May 2, 2014. Or in Kharkiv. In spring 2014, the city was literally teeming with anti-Ukrainian organisations that were coordinated by Russian foreign aid agency Rossotrudnichestvo (Russian Cooperation) in Ukraine: the Russian-Ukrainian Information Centre, Ukrainian Choice, the Political Club of South-East Ukraine, Kievan Rus, Slavic Unity, the East-Ukrainian Centre for Strategic Initiatives, the Working Kharkiv Citizens Union of Ukraine, Borotba (Struggle) and South-East. The militants of Yevhen Zhylin's Oplot fighter club, who were trained at the gym of the same name and later joined DPR military outfits, were particularly active in distinguishing themselves. The first separatist activity in Kharkiv began on March 1, at the instigation and with the participation of Mayor Hennadiy Kernes. The "For Kharkiv" rally gradually escalated into a fight between its participants and Euromaidan activists, ending with the seizure of the Oblast State Administration and the assault of the activists that were defending it, including well-known writer and Kharkiv native Serhiy Zhadan. The Ukrainian flag on the roof of the Administration building was replaced by a Russian one, but it was removed towards evening. On the night of March 14-15, armed Oplot fighters tried to storm the headquarters of the Right Sector on Rymarska Street, but were met with fierce resistance. In the clash, two attackers were killed and five wounded. In the evening on April 6, the Kharkiv Oblast State Administration was recaptured by separatists, who proclaimed the Kharkiv People's Republic, but the next day – following numerous ultimatums – they were forced out by Interior Ministry special forces. This was the starting point for cleansing the city of separatists. Anti-Ukrainian activity began to decline in early May, not least thanks to Ukraine’s control over the suburban trains that regularly brought Russian thugs from Belgorod, a borderline city in Russia, to Kharkiv.

Initially, a significant contribution to preserving the territorial integrity of Ukraine was made by numerous anonymous patriots who, despite the stagnation or separatist aspirations of law enforcement agencies and local authorities, were forced into practically implementing Article 17 of the Constitution [on the sovereignty and territorial indivisibility of Ukraine] by any available means. Cases are known of poorly armed or completely unarmed groups of patriots who operated in Izium, Svatove, Dobropillia and other cities, managing to stop local separatists there.

Translated by Jonathan Reilly

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook