The government’s efforts to trigger political confrontation with “anti-fascist” slogans signal its desperate search for ideas that could consolidate the electorate before the upcoming presidential election after it failed to fulfill its latest improvement promises. Disappointed with their choice, its one-time voters mostly vote with their feet and join the disenchanted category. Most voters ignored the latest local elections on June 2. This trend was already noted in the 2012 parliamentary election, and seems to be continuing. Just 22.3% of all voters cast their ballots in the early mayoral election in Alchevsk, Luhansk Oblast, on June 2. The PR candidate won with barely half of the votes cast, i.e. nearly 12% of all voters registered in the lists. The turnout in Donbas was almost half that of local elections in other regions on that day.

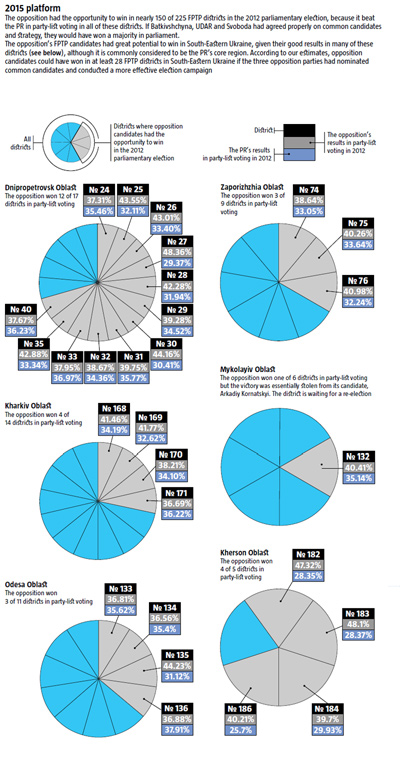

The scale of voter discontent with the current situation in South-Eastern Ukraine is increasing. If they do not switch to the opposition, they could end up under the influence of anti-Ukrainian projects, often supported by Russia. The advocates of separatist initiatives in South-Eastern Ukraine often claim that this region has never been Ukrainian. However, they say this after 200 and 70 years respectively of severe Russification under the Russian Empire and Sovietization under the USSR. This included the 1932-33 Famine that hit the region very hard, oppression during Stalin’s collectivization and industrialization, and the mass resettlement of ethnic Russians to the region. Today, it has the highest concentration of economic assets in the hands of a few major players, mostly oligarchs, who have a monopoly over the financially-dependent population and are following the Soviet-Russian model. Still, every election over the past decade shows that more and more of the local voters are gravitating towards Ukrainian identity and the European choice. Soviet-oriented pro-Russian parties are exhausting their electoral potential here. In September 2007, for instance, BYuT (The Bloc of Yulia Tymoshenko), Nasha Ukrayina-Narodna Samooborona (Our Ukraine-People’s Self-Defence) and Svoboda collectively won 45.6% of the vote in Ukraine. In October 2012, Batkivshchyna, UDAR and Svoboda ended up with over 50%. In the years between 2007 and 2012, their rating grew thanks to the south-eastern electorate. In 2012, 38% voted for the opposition in Dnipropetrovsk Oblast compared to 32% in 2004, and 33% against 26% in 2004 in Kharkiv Oblast. Similar trends were seen in Odesa, Mykolayiv and Zaporizhzhia Oblasts, while Kherson Oblast supported the opposition with 40% in 2012. Support even increased in Donetsk and Luhanks Oblasts. In 2004, 4% and 6% voted for the opposition candidate in the presidential election respectively. In 2012, over 11% supported opposition parties in Donetsk Oblast, and over 12% in Luhansk Oblast. This is not the limit.

Photo: UNIAN

Meanwhile, there is the impression that the opposition is unwilling or unable to offer south-easterners a clear and persuasive alternative to the Yanukovych regime in order to win their support. The Rise Ukraine! rally in Donetsk confirmed this. The protesters were mostly activists of the three opposition parties from several eastern oblasts, many of them from Kyiv and other regions. With only 2,000-3,000 protesters in a city of about a million people, the rally was sluggish and looked like something set up to just tick the box or create some media buzz. The speakers once again repeated the usual list of trivial statements. It looked as if they did not expect to have any effect or impact on the protesters. This once again brought up the long-standing problem of Ukrainian “democratic forces”, which failed to pay due attention to South-Eastern Ukraine, especially the Donbas throughout all the years of independence, viewing it as the domain of the Donetsk guys and a hopeless battle for the electorate. As a result, the East remains essentially segregated from the rest of the country.

Donetsk “elites” have been running the region for decades on end, with barely any subordination to Kyiv. Over this period, a special Russian-Soviet model of administration has evolved in the Donbas. When the PR came to power, it rapidly expanded all over Ukraine. The factors discouraging the opposition from proactive efforts in this region include the “price” of one vote which is two to four times higher in South-Eastern Ukraine compared to, say, Central Ukraine; the lack of due control over local branches by opposition headquarters, making their local functionaries inert and obedient to local authorities; and a high risk of defeat in first-past-the-post parliamentary and local elections that discourages potentially strong and respected candidates from running as representatives of the opposition in this region. There are solutions to each of these problems, provided that democratic forces actually have the will to try and change the country.

IN THE REAR OF THE REGIME

Disenchanted with their “homeboy” government, voters in the south-east deserve closer attention from the opposition for a number of reasons. Firstly, their support may well offset the impact of election rigging. Secondly, it will help the opposition to expand its local platform and use local activists as its observers and election commission members rather than activists brought in from Western and Central Ukraine, which only contributes to the opposition’s image of strangers in the region. Thirdly, the expansion of the opposition’s branches is important, should falsifications trigger protests. Fourthly, the regional divide must be eliminated in order to unite society in a potential confrontation with the regime.

In order to make the most of the potential in south-eastern regions, the opposition has to put more effort into expanding a local platform it can rely on in the upcoming presidential or parliamentary election, whether regular or early, or create it from scratch in some regions. It should pay special attention to urban South-Eastern Ukraine, since the share of urban population in the Donbas is 90%, with 70-80% in other parts of the region. It should put more thought into alternative solutions for the socio-economic problems of the south-eastern urban population, such as unemployment, the closure of mines, stifling of SMEs, distribution of local budgets, environmental issues and the like. The opposition is also very passive in rural parts of the region where administrative leverage has much more impact than in big cities. As a result, predominantly Ukrainian-speaking rural regions gave the PR and the Communist Party more support than did most oblast centres and big cities.

A WAKE-UP CALL FOR THE EAST

The crucial task for the opposition is to offer the disillusioned voters in South-Eastern Ukraine a comprehensible alternative for their region and to explain why they live in misery and how they can escape the vicious circle.

The crucial task for the opposition is to offer the disillusioned voters in South-Eastern Ukraine a comprehensible alternative for their region and to explain why they live in misery and how they can escape the vicious circle.

South-Eastern Ukraine is one of the regions most affected by the oligarchic monopoly. It desperately needs to shed its proletarian legacy and grow a powerful class of wealthy entrepreneurs and liberal professionals, capable of choosing their own position rather than a submissive mass for the administration of public enterprise and entities or oligarchic owners. The opposition has to communicate to people that the social stereotypes imposed in the Soviet past, including the icon of a worker that the state will take care of and collectivism distorted into a herd mentality, leave them with no options other than degeneration and poverty, because they stifle initiative and entrepreneurial skills, which are the key elements of any development. South-Eastern Ukraine, especially the Donbas, is riddled with obsolete enterprises and an economy that have no prospects in their current state. Replacing them with new promising ones that will quickly generate new jobs and income is impossible with current oligarchic monopolies or state-owned enterprises. Private ownership and numerous initiatives that offer a lot of new jobs are the only options that will lead to change. This requires the protection of private ownership and an effective anti-monopoly policy on the part of the government and large-scale lending to promote private business. Meanwhile, it should be explained to the south-easterners who stick to their proletarian Soviet legacy, that the state will never make them wealthier. Its role is not paternalism and the feeding of destructive illusions, but the support and creation of an environment where every citizen can make a prosperous life for himself.

Another important aspect of the struggle for South-Eastern Ukraine is to help its citizens overcome their Soviet stereotypes on language, history, relations between Ukraine and Russia, and Ukraine’s geopolitical and civilization choice that are still fueled by local pro-Russian and the Russian mass media. Double standards, whereby the opposition offers one interpretation of its stance on the language issue and history in the west and the centre, and another in the south-east, are unacceptable. It should stick to a consistent and reasonable position, carefully choosing solid arguments and communicating them to the voters.

Changing stereotypes is difficult but possible. For instance, many south-easterners support the idea of Ukraine joining the Customs Union with Russia. However, most industries in these regions, especially coal mining and steelworks, have strong competitors in Russia. Therefore, they have much better prospects outside the Customs Union. However, since the issue of Ukraine’s membership has been raised yet again, the opposition has failed to explain to Donbas voters why Customs Union membership poses a threat to their coal industry. First and foremost, it should address the younger generation and the middle-aged.

A comparison of 2007 and 2012 election results has revealed a partial shift of generations over these five years, which is the key driver of political change in Ukraine. A new generation of voters born in Ukraine is replacing the old generation of homo sovieticus that bears the inferiority complex of the past. According to exit polls, 40.1% of those who voted for the Communist Party were over 60. Almost 30% of PR voters are over 60 years old. The opposition’s share of voters of this age is 24.7-27.2% for Svoboda and Batkivshchyna and up to 12.7% for UDAR. The generation shift is accompanied by the intellectual growth of voters. 30.9-33.6% of PR and Communist Party voters have incomplete or completed college degrees, compared to 39.6%, 46.9% and 54.2% respectively for Svoboda, Batkivshchyna and UDAR.

Communication with south-eastern voters will not bring an overnight result, especially with the existing obstacles of administrative leverage and deep-rooted Soviet and Russian stereotypes. However, the opposition still has a chance to create a solid electoral platform in South-Eastern Ukraine to remove the current regime of the Family and oligarchs and initiate the transformations that the region so desperately

needs.