On 25 November 2011, Aleksandr Lukashenka surrendered the second part of BelTransGas to Gazprom, while Turkmen President, Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedov, took part in the ceremony of endingthe pipeline to transit Caspian gas to the Pacific coast in Guangdong at the end of his four-day trip to China. This came after he had managed to negotiate another 25bn cu m increase in the supply of Turkmen gas to China with President Hu Jintao.

RUSSIALOOSING ASIA

In soviet times Central Asian countries were hugely dependent on Russia, as much as either Ukraine or Belarus was, despite their abundant gas resources and intense extraction. Under President Yeltsin, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan had opportunities to transit their gas sold to other countries through Russian pipelines, even if this was in exchange for low fees for Russia to transit its gas to Europe. After a few years of Mr. Putin’s presidency, these countries then faced deals ensuring Gazprom’s monopoly on buying all gas they exported for decades to come.

Eventually, though, Gazprom found itself trapped in its own greediness. As the recent crisis unfolded, pushing oil and gas prices into a steep decline while at the same time consumption in Europe shrank, Gazprom refused to fulfill the contracts that guaranteed its monopoly for local gas unilaterally. The better diversified economy of Uzbekistan survived the shock, even though Russia’s reduction in purchased gas by a quarter of the 42bn cu m in 2008 hit Turkmenistan’s extraction-oriented economy hard.

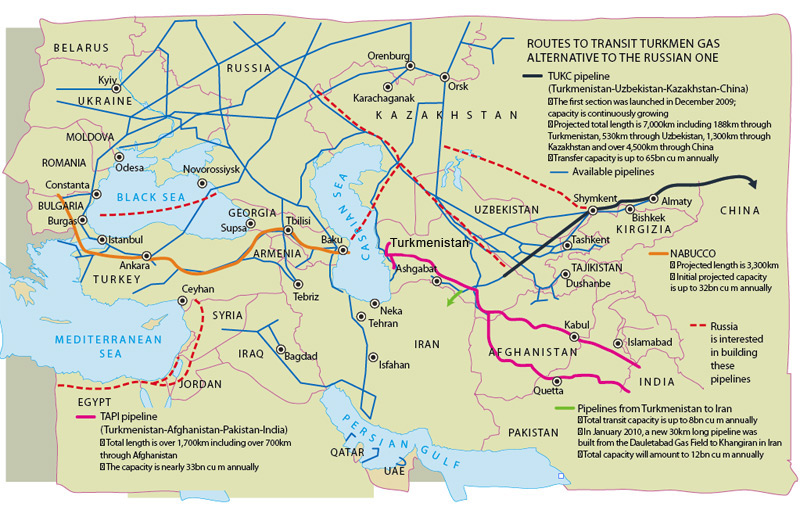

Russia subsequently offered Turkmenistan an increase in the amount of gas it purchased to the 2008 level in exchange for lower rates and wider access to gas deposits for Gazprom. But Ashgabad opted to diversify its export routes that are now readily laid in all four directions of the world. Over 2009-2010, Turkmenistan built gas pipes allowing the country to switch most gas from the Northern route to Russia, southward and eastward, i.e. to Iran and China. As a result, Turkmen gas exports began to grow intensely (33.6% in 2010), while the abovementioned countries purchased 1.5 times more gas than Russia, with 12 and 14bn cu m compared to 10bn cu m respectively.

This gave Turkmenistan a dynamic growth of investment, worth a total of US $9.7bn in that year. And over 9 months of 2011, the amount of investment hit US $8bn or 45% of GDP. The arrival of foreign investors resulted in the quick exploration of natural gas deposits that now amount to 44.25tn cu m according to the Gaffney, Cline & Associates, a British consultancy firm, including an already confirmed 25.1tn compared to Gazprom’s 19tn. The national program for 2011-2013 provides for an up to 230 and 180bn cu m annual increase in Turkmen gas extraction and exports which is roughly the equivalent of what Gazprom is currently exporting outside the CIS Customs Union.

The launch of the first section of the Turkmenistan-China gas pipeline in December 2009 was the first in a series of hard knocks to the plans of expansion for the Asian part of the “energy empire,” a popular name for Russia among its own top officials. Firstly, this has ruined Russia’s monopoly in exploiting resources in Central Asia; secondly, this dims the prospects of Russian gas exports to the vast Chinese market. According to CNPC, the Chinese state-owned oil company, China is going to import 30bn cu m of gas from Turkmenistan in 2012. After the pipeline is extended to the economically advanced shoreline provinces, with the recent pipeline ending ceremony by Messrs. Hu and Berdimuhamedov as one of the steps to draw the plans closer to conclusion, Turkmenistan will be pumping up to 65bn cu m of its gas to China by 2015.

Kazakhstanand Uzbekistan also look willing and prepared to sell most of the gas they export, i.e. 12-15 and 10bn cu m respectively, to China. Of course, this will question the need, amounts and deadlines for Russian gas supply to China in the next decade, as well as the diversification prospects of its gas markets Russia has been using to blackmail Europe every time their gas relations get tenser.

Another project being intensely built is TARI, a 1.700km long pipeline from Turkmenistan to India that runs through Afghanistan and Pakistan with a capacity of up to 33bn cu m. It is supposed to take Middle Asian gas to the Indian Ocean coastline, thus supplementing the Iranian section of the South Stream. In mid-November 2011, Pakistan and Turkmenistan agreed on a gas price for the former, while Gazprom is now competing for the right to take part in the project – without much success though, according to a tough comment made by the Turkmen Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Ashgabat insists on considering the prospect only after the four countries complete their negotiations and launch the pipeline.

IMPORTANT NABUCCO

Currently, the process between transiting parties and consumers of agreeing a supply of 40bn cu m of Turkmen gas to the EU through the Trans-Caspian gas pipeline and Nabucco, is already on the finish line. In early November 2011, Mr. Berdimuhamedov confirmed that “the export of fuels to Europe is the most important component of Turkmenistan’s foreign policy strategy,” despite Turkmenistan’s interest in Asian markets for its gas, “thus the Transcaspian system is a very significant project.”

Moreover, the project has now become a matter of interest for France and Germany, two key players in the EU, in addition to the European Commission. In April 2011, France signed a declaration of cooperation in its energy sector with Turkmenistan. On 17 November 2011 during his trip to Ashgabat, Guido Westerwelle, German Minister of Foreign Affairs, said he was “sure that the talks on Nabucco would have a successful outcome and both Turkmenistan and Azerbaijan would join the project”. Azerbaijan is planning on building a joint underwater gas pipeline with Turkmenistan despite the stonewalling of “defining Caspian legal status,” that is determining the Caspian Sea as the sea, or lake, with the relevant division of its underground area and control over its surface.

MOSCOW, AFRAID AND BLUFFING

Moscow’s response to all this is fairly sensitive. Dmitri Medvedev has claimed the construction of the Transcaspian Pipeline without the consent of all Caspian countries is impossible, while Konstantin Simonov, Chairman of the Russian National Foundation for Energy Security, has threatened other parties that Russia’s response will be “tough, and probably in a military form.”

Yet, Western countries have acted decisively. Richard Morningstar, Special Envoy of the United States Secretary of State for Eurasian Energy, and his advisor Daniel Stein have said in both Baku and Ashgabat respectively that “no force will interfere” once the EU, Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan agree on the implementation of the Transcaspian pipeline. Matthew Bryza, US Ambassador to Turkmenistan, stated that the US is already thinking of ways to help Azerbaijan protect its energy infrastructure on the Caspian basin.

Russiawill have nothing to outweigh gas deals between the EU and Central Asian countries, particularly if supported by the US and NATO. By contrast, a plausible prospect is for Russian diplomacy to intensify its efforts in Europe, the consumption end of the new gas chain. It has always been based on “caring about the energy security of Russia’s European partners,” segregating them with all kinds of privileges and stories about the “ephemeral Russian threat” and “lack of reason behind the European search for an alternative to its conventional reliable partners.” Also, Russia might try to affect the situation in Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan internally by discouraging their ambition for proactive independent steps. As Transcaucasia and Middle Asian states intensify efforts to use their resources for their own good, Russia looses much of the leverage it needs to play the energy game with the EU and China successfully.