Two months ago, the term ‘monomajority’ entered the lexicon of Ukraine’s pundits, journalists, and most Ukrainians who are more-or-less paying attention. However, the debate over the nature of this monomajority rages on. After Sluha Narodu demonstratively worked in fire-engine mode, the question arose as to just how far and where such a legislature might take the country.

Yet, in the third week of September, unknowns were added to this equation. The Verkhovna Rada unexpectedly failed on two votes – both times thanks to members of the presidential faction. Indeed, it looks like more surprises are in store for Ukraine. However, it’s not enough to track what’s going on in the Rada to understand the current political process. It’s just as important to have some understanding of just who these “servants of the people” are and what forces of Ukrainian society they represent.

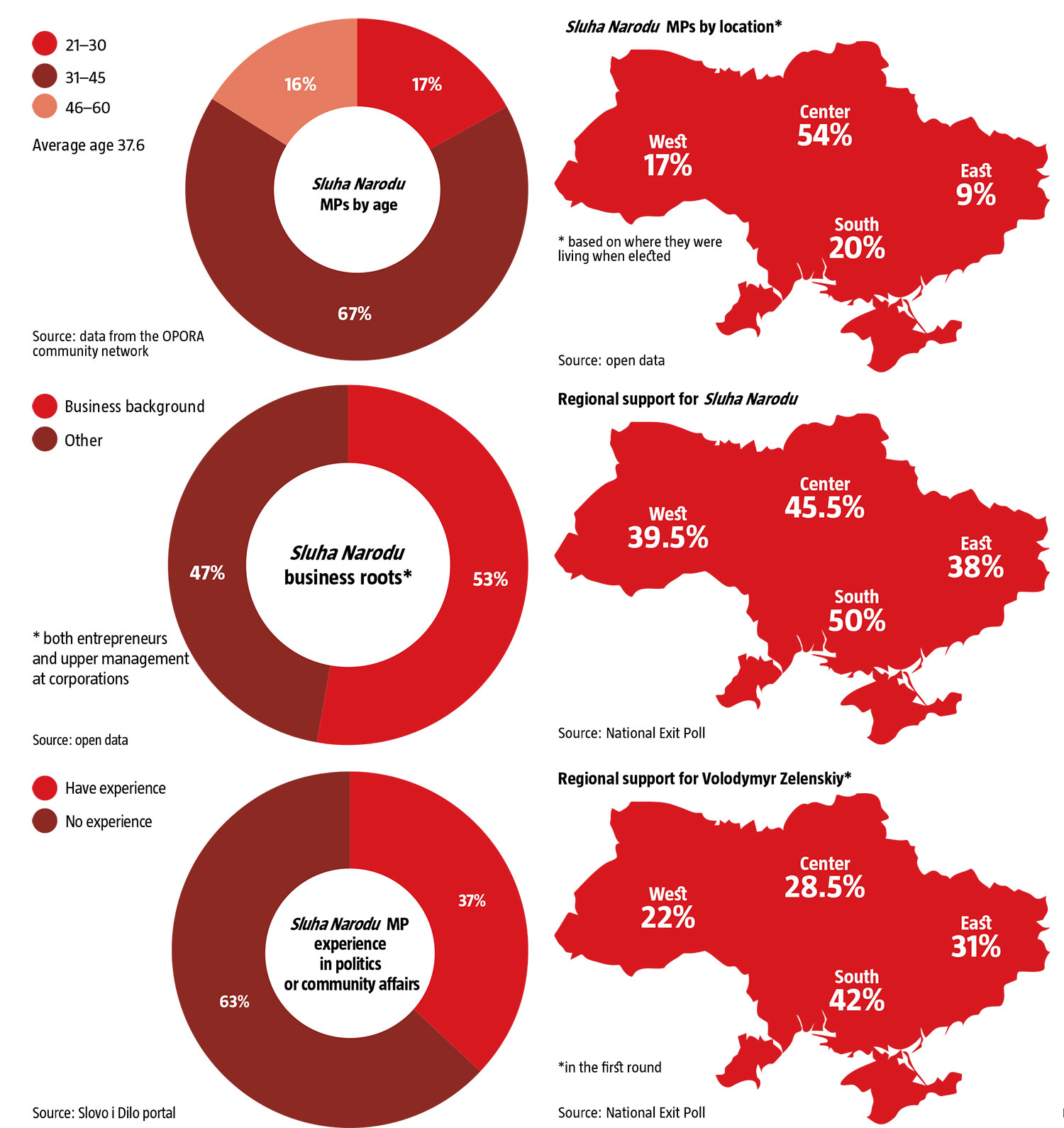

How and how much the 9th Convocation of the Verkhovna Rada differs from its predecessor has long been written up. The social profile of Sluha Narodu can be outlined briefly: the president’s faction firstly distinguishes itself in that all of its members are new faces, that is, they’ve been elected to the Rada for the first time. What’s more, according to the Slovo i Dilo portal, nearly 90% have no previous party affiliation of any kind, while 63% have no previous experience in civic activities. Next, they are relatively young, with the average age slightly below 38, making this convocation the youngest in the history of independent Ukraine. Moreover, 52.6% come from the business environment and upper management. But there is also a significant portion that represents small business and physical entity-entrepreneurs (FOPs). In terms of where they come from, 54% come from Kyiv and central oblasts of Ukraine according to official data, the south takes another 20%, and while western Ukraine takes 17%. Only 9% come from the east. Interestingly, the collective portrait of the monomajority coincides pretty accurately with the country’s main “servant,” President Volodymyr Zelenskiy: at 41 he is Ukraine’s youngest president, he has a university degree, he comes from the southeast, and was elected straight out of business.

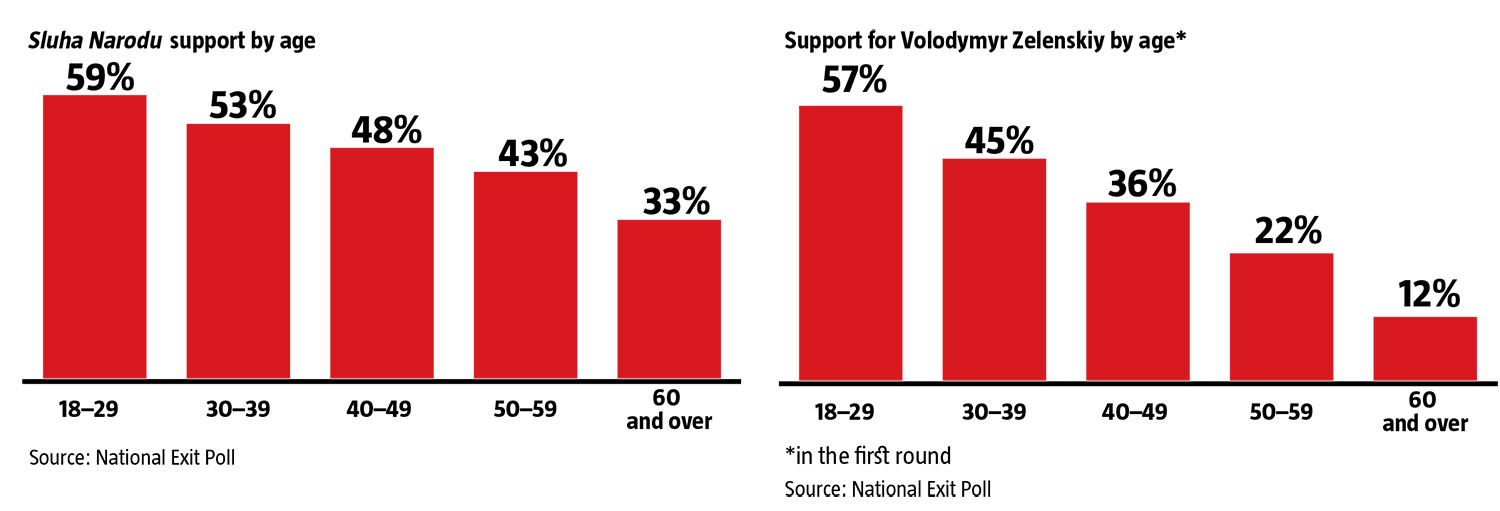

Meanwhile, a closer look at voters shows that those who elected the current government have similar features. According to the National Exit Poll, the Sluha Narodu party won across all age groups but showed greater support among the young: nearly 60% of those age 18-29 voted for SN, reflecting closely the 57% of that age group that voted for Zelenskiy himself in the presidential election. In other age groups, support for Zelenskiy and his party was noticeably lower. In some sense, young voters are also “new faces,” as this segment was considered until now the most passive and traditionally showed the lowest turnout among voters.

Support for SN was considerably stronger at 53% among voters with an incomplete post-secondary education, that is, among students. This was true for Zelenskiy himself as well: he had more than 42% of the student vote in the first round of the presidential election. Unfortunately, there is no information about the professional backgrounds of voters. Still, the SN students and entrepreneurs are united by the fact that those with a higher education at least formally belong to the middle class, where the qualified professionals also are today.

RELATED ARTICLE: Middle ground

Regionally, the most support for SN was in the center and southern Ukraine. Where in Lviv and Donetsk Oblasts, Zelenskiy’s party got 22% and 27%, in Kyiv and Dnipropetrovsk Oblasts it got 46% and 57%, according to the CEC. The picture with Zelenskiy himself was very similar: in the first round of the presidential election, he got 42% in the south, and very similar results in the center at 29% and the east with 31%, with the least in western Ukraine, 22%, according to the 2019 National Exit Poll.

The 2019 electoral map substantially differs from the traditional division of the political field into central-western (post-orange) and southern-eastern (post-regional). Neither Sluha Narodu nor Zelenskiy can be easily categorized into the pro-European or pro-Russian camp. Based on the portrait so far, it seems, logically, that they represent the interests of the relatively young middle class and those who would like to join it. The regional aspect can be explained as the Zelenskiy electorate being less ideologically inclined and therefore less loyal to both the pro-European and pro-Russian parties. It also looks like the typical Zelenskiy and SN voter is a new category of Ukrainians who have outgrown the old divisions between relative West and East and refuse to think politically in terms of coordinates, linguistic, historical, geopolitical issues, and so on. Still, this analytical conclusion is very original—and very wrong. The link between the “servants of the people” and their voters exists, but it’s on a completely different plane.

First of all, it’s important to look carefully at the conditions under which this new government came to be. The electoral success formula of the main “servant” of the country has long been figured out. Zelenskiy received the mace of power only because he took advantage of the right moment –or was taken advantage of at the right moment – becoming a symbol of the protest mood and riding on a wave of mass emotion. This allowed him to take over the presidency on a fast-track basis, despite having no previous political history at all.

His party was no different. It’s no secret that Sluha Narodu was slapped together at high speed within a few months before the VR election. Based on projections by pollsters, the human resource gap was enormous and had to be filled by whatever was close at hand. As a result, the Verkhovna Rada suddenly had a faction that was largely formed by accidental MPs. “There are fruit sellers, wedding photographers, all kinds of different people… some of them insane or psychologically ill,” says Andriy Bohdan, Chief-of-Staff at the Office of the President in describing the presidential faction. “It’s a real cross-section of society.” It’s hard not to agree with him. Among these “servants of the people,” certain common traits can be seen such as the newness of their faces, their age, and their geographic origins, but these are all fairly vague features that create a completely arbitrary portrait.

What unites them far more is the very brand, “servant of the people,” under which they entered the Verkhovna Rada, even though this may seem a fairly nominal trait. The only basic characteristic that is common to all the MPs of the monomajority is that they entered Big Politics as a result of strictly situational factors. Their actual role in this process was marginal, as their victory was completely and fully ensured by the personal brand of Zelenskiy-as-Holoborodko.

This is equally true of those who voted for the country’s “servant-in-chief.” The mythologized 73% who voted for him in the second round, or even the 30% who voted for him in the first one, do not constitute some kind of socio-political unit. Although some kind of social portrait of the Zelenskiy or Sluha Narodu voter can certainly be put together, it’s impossible to say for certain that this is the face of the Ukrainian middle class, Ukrainian youth, central-southern voters, or any other stable collective entity. For one thing, the Sluha Narodu voter only emerged in this year’s presidential and VR elections, whereas the political profile of central-western and southern-eastern regions was built up over decades, so it’s early to say that this trend has been broken for good. In May 2014, Poroshenko’s victory in all parts of the country was also hailed as unifying East and West. But opinion polls have shown that ideological markers regarding history, language, the war, geopolitics and a number of other issues shift far more slowly: the old divides have still not disappeared. Poroshenko could credit the situation at the time, especially the collapse of the pro-Russian camp, for his nationwide victory.

The Zelenskiy-Sluha Narodu voter similarly emerged as a result of the specific circumstances at this time. It’s unsurprising that the election campaign of the current administration was built around effective show-business effects, and not on the specifics of a platform: the latter could have easily splintered their very eclectic electorate. Zelenskiy was able to take advantage of the protest vote. The main motive driving those who voted for Sluha Narodu was the desire to ensure support in the Rada for President Zelenskiy. Similarly, what motivated people to choose a specific candidate in FPTP ridings was whether the individual was a member of SN or not. Moreover, party affiliation proved far more important than the personal qualities of the candidate according to the 2019 KIIS poll.

And so it seems that the only feature that can identify the electorate of the current powers-that-be is dissatisfaction with the previous administration. In this sense, Zelenskiy, his team, and his legislative guard really do reflect their electoral constituency: all of them arose due to external circumstances and are unlikely to form a long-term unity. In order to do so, they will have to undergo an internal maturation process, forming common values, a basic platform, a political identity, and so on. Indeed, few Ukrainian parties have managed at different times to go along this path, or at least a substantial part of it.

It’s hard to say whether the servants of the people will move in this direction. It’s quite possible that the party will remain a classic example of a political overnight sensation that proves short-lived despite its enormous success. Otherwise, both the SN factions and its voters can expect times to get tough. The feelings of protest that brought them together and pushed them into the pages of history will sooner or later die out. When that happens, the old existential questions that SN leadership so confidently promised to “take out of the equation” will fill the agenda all on their own. Will the resolution of these issues lead to a split in the Rada’s monomajority? Not necessarily. It’s also possible that the crystallization of specific political content could actually strengthen it. Even so, Sluha Narodu is unlikely to hold onto its current electorate. More likely, Zelenskiy’s party will find its niche in the camp of relatively pro-European or pro-Russian forces. The contradictions that lie at the foundation of these divisions will be possible to forget at some point. But, so far, no one has managed to take them out of the Ukrainian equation.

RELATED ARTICLE: The force of evolution

Translated by Lidia Wolanskyj

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook