Results of the second round of presidential elections in Ukraine proved to be a fertile ground to various members of the Russian fifth column in Ukraine – equally among politicians and representatives of the pro-Russian media. They decided the time has come for them to claim that Ukrainian society demands a radical change of the strategic direction. The key thesis of their propaganda was a claim was that Ukrainian society firmly rejected president Poroshenko’s internal and foreign policy. Therefore, as they imagined it, if not the new president, then at least the new parliament will make a drastic shift in country’s foreign policy and will turn its sight back to Russia. Those tendencies are somehow also noticeable among pro-Ukrainian and pro-European citizens. However, Poroshenko’s defeat to Zelenskiy in the second round absolutely does not mean that Ukrainian society wants the change in the country’s foreign policy, or that Zelenskiy’s voters somehow demonstrated their stance against European aspirations, de-Sovietisation of Ukrainian public space and culture, or against country’s top priorities which were identified by Poroshenko – “Army, Faith and Language”. Results of the vote after the first and second round of elections have clearly proven that Poroshenko simply failed to convince majority of Ukrainians that his defeat would mean a radical shift in Ukraine’s geopolitical and ideological strategy. Poroshenko lost not because of the “Army, Faith and Language”, or his foreign policy, but because of the poverty, rising living costs and corruption. At the same time, the main aim of the fifth column right now is to convince Ukrainians that Zelenskiy’s victory means a decisive defeat for the foreign policy initiated by Poroshenko, and if Zelenskiy is not going to change anything anytime soon, he would lose the popular support as well.

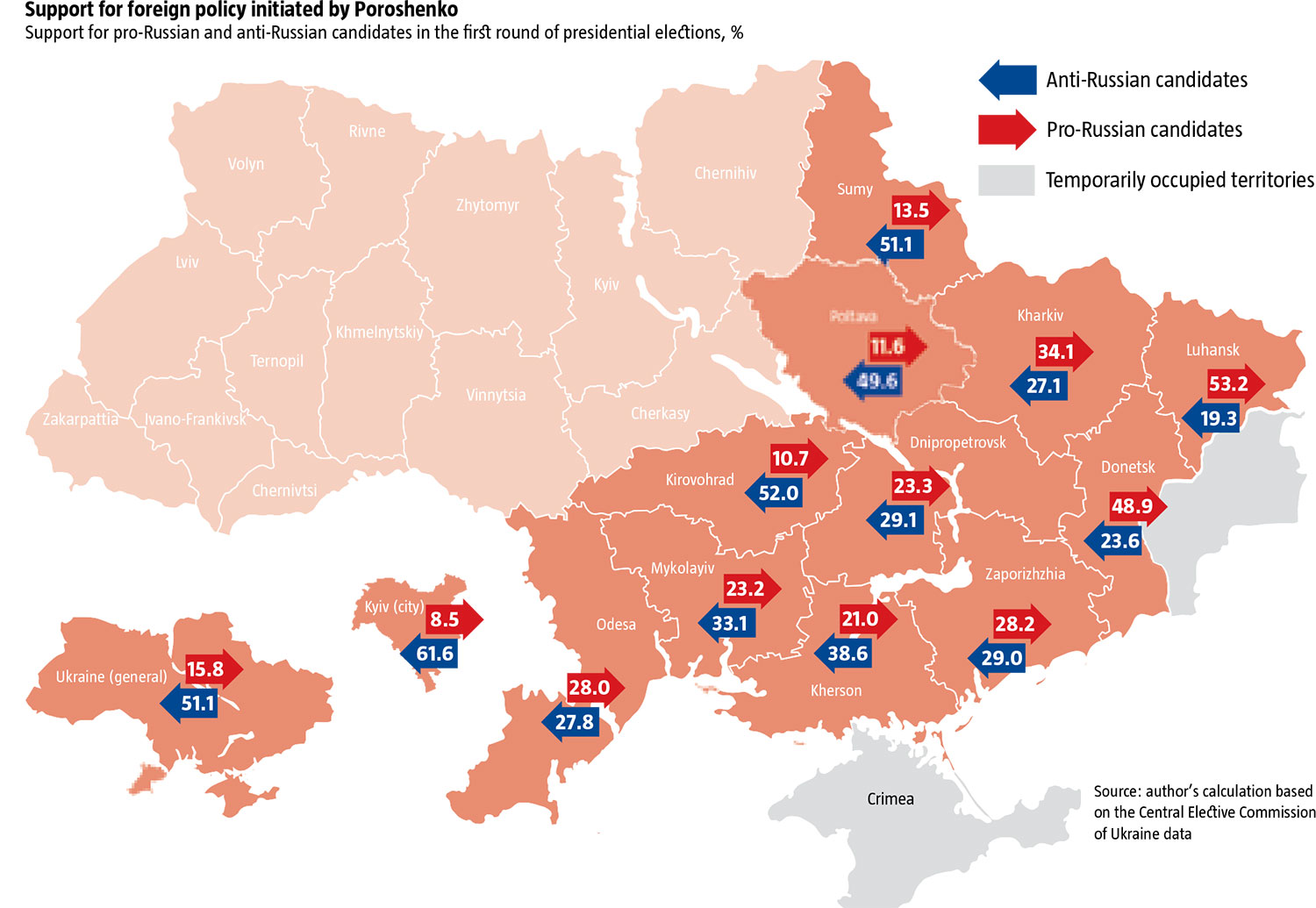

In reality, results of these presidential elections, and especially those after the first round, when people traditionally vote “for” a specific candidate, rather than “against” one, have proven something completely opposite. The absolute majority of Ukrainians, including those living in the East and South, support Ukraine’s efforts to move away from Russia with further integration with the European Union. Openly pro-Russian candidates, such as Yuriy Boyko and Oleksandr Vilkul together earned only 15.8% of all votes in the first round, which is barely 3 million votes. Politicians with clear anti-Russian positions (Poroshenko, Hrytsenko, Tymoshenko, Smeshko, Lyashko, Koshulynskiy, Nalyvaychenko, Bezsmertniy and others) received over 51% of the voters, or 9.5 million votes. Together Boyko and Vilkul received majority of the votes in the Ukraine-controlled areas of Donbas region, as well as a third of votes in Kharkiv region. Elsewhere, even in the South East they received less than anti-Russian candidates. For instance, in Zaporizhzhia region Boyko and Vilkul together received 28.2%, while anti-Russian candidates received 29%, in Odesa – 28% and 27.8% respectively. In other regions in the South and East they have done even worse – in Dnipropetrovsk region they lost 23.1% to 29.1%, in Mykolayiv region – 23.2% to 33.1%, in Kherson region – 21% to 38.6%. No need to mention other areas, where they barely earned 10%. In Ukraine’s capital, Kyiv, pro-Russian candidates received together 8.5%, while anti-Russian group of candidates won 61.6%. In Kirovohrad region Boyko and Vilkul lost 10.8% to 52% won by anti-Russian candidates, and 11.6% to 49.6% in Poltava region.

RELATED ARTICLE: Predictable revenge

Zelenskiy’s choice options

Current tendencies in Ukrainian society make it impossible for a candidate or a political party, who openly calls for the restoration of close ties with Russia, to be elected, let alone hold onto the power for some period of time. It seems like the close circle of the newly elected president began acknowledging this fact. Despite that Zelenskiy’s voters are quite diverse in terms of their political views, he will still be forced to openly declare his anti-Russian stance, which will open up a door for him to cooperate with other anti-Russian political parties, as well as securing support from their voters. Potential loss of the voters, who are fierce devotees of the so called of “reload” and “peace-making” with the warmongering state and its puppets in Donbas, is somehow seen as a lesser of two evils by Zelenskiy and his team. Recently Zelenskiy caused uproar among some of his followers on Facebook, publishing a post claiming that after a careful consideration he “realized that after the annexation of Crimean peninsula and Russian military intervention in Donbas, there is nothing common left between Ukraine and Russia, but the state border” and he definitely “wouldn’t call current Ukrainian-Russian relationship a brotherhood”.

His pro-Russian followers and supporters as well as member of the Ukraine’s fifth column hoped that Zelenskiy’s victory would in fact lead to a significant U-turn in Ukraine’s Russian policy. They have immediately showered him with angry accusations, claiming he has bitterly disappointed their hopes and threatening that “pro-Russian citizens will elect pro-Russian parliament”, calling on Zelenskiy to “unite the nation rather than divide, and adhere to his promises”. At the same time Zelenskiy is forced to acknowledge that even before the first round of elections 53.3% of his voters supported Ukraine further integration with Europe, while 45.4% supported Ukraine’s accession to NATO (as opposed to 32.6% who were against it). Result of the second round drastically changed the geopolitical picture of Zelenskiy’s voters – he increased his support by 43%, while pro-Russian Boyko and Vilkul remained with their 15.8% of support. Thus, the anti-Russian and pro-Western majority among Zelenskiy voters has increased even more. According to Kyiv International Institute of Sociology (KMIS), before the second round of Ukrainian elections 44% of his voters were Ukrainian-speaking Ukrainians, 23.8% were bilingual and only 28.2% were Russian-speaking.

Change in the strategy is an important issue once we look at Zelenskiy’s future cooperation with the parliament and the local authorities. According to KMIS, pro-Russian parties, such as Opposition Platform for Life (OPZZh) of Medvedchuk, Opposition Block of Akhmetov-Novinskiy and Nashi of Murayev would only win 19.1% of votes, while Block Petra Poroshenka (BPP), Batkivshchyna, Civic Platform (GP) of Hrytsenko, Samopomich, Vakarchuk’s potential party and UKROP would win 49.4%. It also seems like in every region, except for Donbas, the anti-Russian forces would win. Another 25.9% would vote for Sluga Narodu, Zelenskiy’s political party. In the South of Ukraine, OPZZh, Opposition Block and Nashi would win 30.2%, while combined anti-Russian parties would have 31%. This equation would constitute 36.2% and 27.3% in the East, while Sluga Naroduwould get 28.1%. Needless to say, in the Central Ukraine, pro-Russian parties would barely receive 7.1% of the votes, while anti-Russian BPP, Batkivshchyna, GPof Hrytsenko and Syla i Chestof Smeshko would receive 58.4% of the votes. In the west of Ukraine pro-Russian parties would barely reach the 4% of support. Those pro-Russian parties, however, would have received 73.7% in the Ukraine-controlled areas of Donbas, as opposed to 6.5% won by anti-Russian parties.

It seems like the sole viable option for Zelenskiy and his political party is partnering in the parliament with pro-Ukrainian and anti-Russian forces. Firstly, because this would mean support from at least of 50% of Ukraine, except for Donbas. This means, 55.4% support in the east, 66.7% in the south, 87.6% in the centre and 89.6% in the west. At the same time, if Zelenskiy chooses to partner with the pro-Russian parties, he will create a dangerous situation and growing opposition not only in the west, but also in the centre of the country. Even now Zelenskiy is seen as the representative of the South, who does not have significant support among Ukrainians living the central or western regions and who won the second round of elections mostly owing to corruption scandals surrounding Poroshenko.

At the same time, one should also remember about the classical competition between Kolomoyskiy, the sponsor and the key man behind Zelenskiy, and Akhmetov and Novinskiy, who are behind the Opposition Block. Kolomoyskiy also has quite a strained relationship with Dmytro Firtash, Vienna-based Ukrainian oligarch and the sponsor of OPZZh. Kolomoyskiy, Zelenskiy and their circle may be absolutely indifferent or at times even ignoring Ukrainian national aspirations, such as Ukrainisation, de-Sovietisation or de-colonisation of the cultural sphere in Ukraine. But they would absolutely support Ukraine’s movement towards the West, if they see strengthening of the ties with the West as something more profitable, than trying to come to an agreement with Kremlin or its satellites. Additionally, Kolomoyskiy may be tempted by the assets of pro-Russian oligarchs in Ukraine. And it is much easier to get hold of those once he declares himself in the opposition to Kremlin.

Therefore, Zelenskiy is doomed to search for strategic partners among pro-Ukrainian and pro-Western political forces, rather than the pro-Russian Kremlin’s fifth column. This will also increase his popularity in the regions, where his support initially was not that strong. He will have to, though, correct his rhetoric and get rid of his image as a soft politician, ready to compromise with Moscow or with pro-Russian politicians such as Medvedchuk or Lukash – which he has been actively trying to prove recently.

RELATED ARTICLE: Anticipating revenge

Endless opposition

Medvedchuk’s OPZZh is not denying that they have a lot of hope in the upcoming parliamentary elections in the fall 2019. According to Ukrainian constitution, presidential power in Ukraine is rather limited. According to pro-Kremlin “team”, it is much more effective to have fragmented parliamentary coalition, which would influence both president and the prime minister and which would be ruled by the ‘eminence grise’. In order to influence the parliamentary coalition, such marginalized political players like OPZZh will need divided parliament and a weak president.

If Zelenskiy opts for a partnership with pro-Ukrainian forces, pro-Russian fifth column will still be able to form some sort of a parliamentary representation, especially using the votes of the Zelenskiy’s disappointed voters of the East and South. However, the Latvian example proves that this will not be enough. In Latvia, pro-Russian Saskanas Centrshas been one of the biggest parliamentary forces in the Latvian parliament for years, claiming from 25 to 30% of the seats. This, however, failed to influence Latvia’s further integration with Europe and NATO.

At the same time, political parties in Ukraine that are still hoping to bring the country back into the Russian sphere of influence, are aware of the fact that possibilities to do so are shrinking. This, in turn, makes them more aggressive and reckless, forcing them to use new methods in a political environment, when openly pro-Russian candidate stands no chances. In this case ambitions of the pro-Russian fifth column in Ukraine may only be fulfilled as a result of a coup d’état or power seizure.