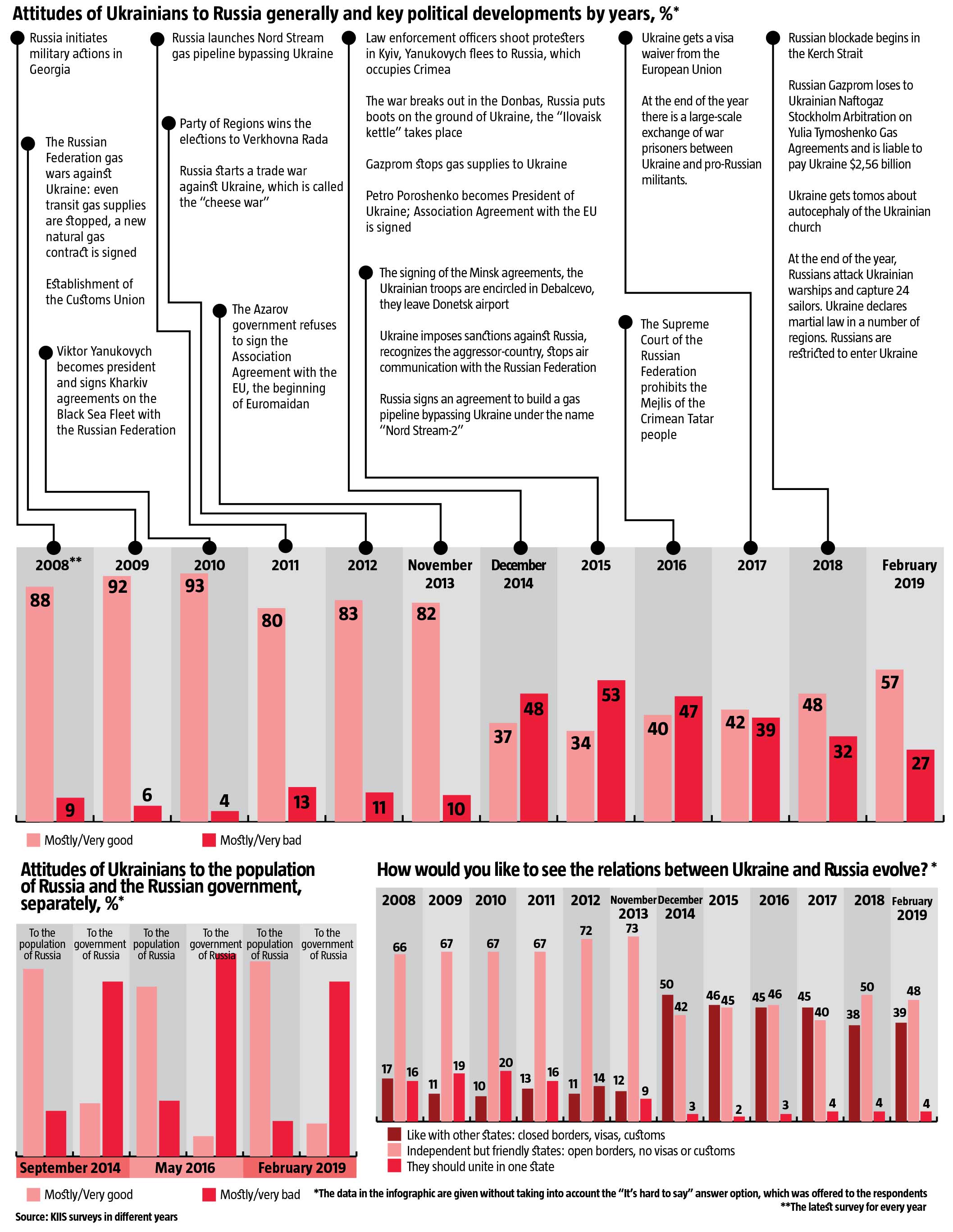

Sociologists revealed troubling data in February 2019: the share of Ukrainians sympathizing with Russia went up almost 10% to 57% (Kyiv International Institute of Sociology, February 2019). Based on KIIS data, the fast growth of positive attitude towards Russia began in 2018. Unless this trend changes, Ukraine will go back to the prewar level in several years (see Attitudes of Ukrainians to Russia generally and key political developments by years) even if Ukraine-Russianrelations have barely seen any change.

Why are Ukrainians increasingly sympathetic with Russia? The decline of 2014-2015 radicalization may be one explanation. Society may be getting used to the war as it transforms into the background of everyday life from the shocking disaster initially. The Russian aggression has thus not become the point of no return for Ukrainians: the surge of anti-Russian sentiment reflected the peak of emotional reaction rather than the profoundness of mentality transformations. KIIS sociologists also assume that the media have affected the sentiments as pro-Russian forces have been more proactive in the runup to the election. This is an equally troubling signal of the fact that the Kremlin’s propaganda still influences public opinion more than the Ilovaysk tragedy or the attack against Ukrainian sailors in the Sea of Azov. The factor of propaganda should not be considered as the sole one: Ukrainians have high mistrust for the media and politicians. But the media activity of pro-Russian forces has shown that public demonstration of such sentiments is no longer a taboo. The respondents have become more open in surveys which, too, affects the overall results. Clearly, none of the above factors are exhaustive, but the fact is that many Ukrainians sympathize with Russia. This could become a political problem for Ukraine.

Sympathy with Russia is the basic prerequisite for the revival of the pro-Russian political camp. Obviously, nobody will promote the Customs Union – ideological rearmament is necessary here. It looks like Russia’s interests in Ukraine will be promoted under the slogans of stopping the war, fighting extremism, revival of mutually beneficial relations and more. The typical Great Russian chauvinism will probably be disguised in liberal phrasing: resistance against decolonization will be presented as struggle for the rights of the minorities, civic freedoms, multiculturalism etc. Pro-Russian politicians can count on the large numbers of average citizens unhappy with decommunization, the ban of Russian films, the blocking of Russian social media, language quotas etc. Putting all this under one policy and presenting this to the voters in an acceptable shape is a purely technical task. The forces involved did not rush to do this in the past years as excessively pro-Russian activity could have faced a disproportionate response from the radicalized society. But the mood is changing today. The result of the current election will show the Russophiles that they are not so few after all. This is not just about the voters of Yuriy Boyko or Oleksandr Vilkul. Volodymyr Zelenskiy, too, is broadcasting pro-Russian narrative with his proposals to kneel before Vladimir Putin for peace and the blatantly anti-Maidan and Ukrainophobic jokes. The presence of such characters in mainstream politics and their electoral results signal that the hawkishness against Russia dominant in the public space until recently is no longer a no-alternative option. In 2014, politicians massively switched to patriotism in order to stay in the political arena. Now, the opposite process may start. When they sense the change of status quo and the new limits of what is allowed, candidates for power at all levels will work for the pro-Russian audience more proactively. They can hardly expect to get political revanche without the electorate in the occupied territory in the short-term prospect. But they have every chance to strengthen their position in the regions.

RELATED ARTICLE: Where’s brotherly Russia when you need it?

There is another serious, if less obvious threat. According to sociological surveys, the attitudes of Ukrainians to Russia, its leadership and the Russians are differentiated. 57% sympathise with Russia, just 13% with its leadership, and 77% are positive about the Russians (KIIS, February 2019). The upside of this is that Ukrainians are not sympathetic with the Russian authorities. In the future, however, the diversified attitudes towards Russia, the Russians and their leadership may result in political problems in Ukraine. Vladimir Putin is not a fairy tale eastern despot. Just like any authoritarian chieftain, he primarily serves the interests of his circle. Self-isolation from the world which Russia has embarked on in 2014 is not just to satisfy personal ambitions of the leader, but to prolong the life of its regime first and foremost, of which the specific group of the Russian elite – the “Ozero cooperative” and others – are beneficiaries. As soon as the Kremlin’s elite decides to reset its relations with the West, Putin and the most scandalous functionaries of his regime will be removed in one way or another, from power at least. After that, they will be declared the scapegoats for everything, from political repressions and the destruction of the economy in Russia to the annexation of Crimea and the war in the Donbas. It is for this reason that Russia’s leadership has been pretending for the last two decades that anything happening in the country is Putin’s personal will. This performance is intended both for the domestic and the external audience. The latter includes Ukrainians, some sincerely believing that the Russian society is a silent hostage rather than an active co-author of Putinism. When the regime collapses for one reason or another, sympathy for Russia will grow further in Ukraine, especially if Russia’s new government declares a vector towards peace and democracy.

Last year’s presidential election in Russia showed that Ukraine has no real friends in Russia, even in its liberal opposition. However painfully and courageously Aleksey Navalny or Kseniya Sobchak criticize Russia’s government, their attitude towards Ukraine remains essentially imperial. Not everyone realizes this in Ukraine. Many in Ukraine’s liberal political camp and non-government sector are willing to hold the hand out to “the good Russians”, especially if they come to power through a wave of mass protests presenting themselves as “the Russian Maidan” and make a few friendly gestures towards Ukraine. This will be a gift for the pro-Russian camp in Ukraine: promoting “normalization of relations between neighbor countries” will become much more comfortable if the Kremlin revamps itself slightly to look more European. It is clear, however, that their essence will not change: Moscow will keep trying to hold Ukraine in its geopolitical orbit regardless of what ideological framework it will take – of the Russki Mir slogans or of a “common movement towards peace and democracy”. In this sense, Ukraine’s best chance for fast decolonization is now when Moscow proves fully inadequate, intimidating Ukrainian liberals with arrests for posts on social media, and average Ukrainians with its talk about nuclear ashes. As soon as Russia puts on a democratic mask, Ukrainian society will once again split into those who will happily stop the resistance and those who realize that Russia’s appetite for Ukraine began well before 2014, and that the imperial ambitions are not the whim of its bad president but a cornerstone of Russia with its political order, culture and identity. It is the latter that many Ukrainians fail to realize, as the sociology shows.

It is impossible to wipe out pro-Russian sentiments quickly for objective reasons. The average age of Ukrainians is 40 – their cultural burden is obvious. It takes time and consistent work by the respective institutions to deliver massive profound change in the minds. The products of educational, cultural and historical policy will be visible later when the identity of young Ukrainians shapes under their umbrella. Yet, we cannot expect a fantastic result. Firstly, all institutions in Ukraine are weak and insufficiently effective. The work of the Ministry of Information Policy has shown that government interference in any sphere does not guarantee fast and good results. Secondly, nobody has monopoly on information or absolute authority in the 21st century, so the efficiency of educational work is always below of what one could expect. Quite a few Ukrainians listen to the crazy and ignore the authority of the state, medicine and global science in matters like vaccination. So pro-Russian sentiments will stay in Ukrainian society much longer. To what extent they will impact the position of Ukrainians in other issues, such as NATO and EU membership and more, is another matter. The cultivation of a new Ukrainian identity which would be impossible to return to the Little Russian format depends on how long and consistent Ukraine’s efforts in this field are. This, in turn, heavily depends on the current political situation.

RELATED ARTICLE: Hybrid hegemony

It is too early to speak about the pro-Russian revanche. But the “moderate” forces are perfectly capable of pausing the decolonization as they avoid any measures that could lead to controversial reactions from society. These measures have included decommunization, the blocking of Russian social media and others. The general election is a factor of risk in this sense as the preferences of the audience can tilt in any way. In an environment where public policy is done as show business the mechanisms of democracy start working in unpredictable ways. In practice, however, state policies are defined both by the sentiments of the wider public, and the position of civil society — a domain of street activists, intellectuals, functionaries of non-state organizations, politicians, volunteers, media people, artists, officials and many more. Civil society is quite amorphous in the organizational sense and very diverse in the political sense. Yet it holds strong social, symbolic and political capital. Therefore, it can influence those in power that remember the lessons of the Maidan, and the wider audience when consolidated. Unlike the current leadership of Ukraine, its civil society is not as dependent on public sentiments. It is thus largely responsible for how consistent and long-lasting the decolonization of Ukrainian mass consciousness is going to be.

Translated by Anna Korbut

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook