If the latest polls are to be taken at face value, the frontrunners in the presidential election are easy enough to identify. It’s probably safe to assume that Ukrainians will be choosing among three candidates with the highest ratings: Volodymyr Zelenskiy, Petro Poroshenko and Yulia Tymoshenko. A few other candidates are breathing down their necks, but whether any of them can break into the top is not evident from their ratings.

But the ratings are not showing a lot more that is interesting, including elements that could shed some light on the subtler aspects of the process, such as the geographic profile of voter preferences. The Ukrainian Week decided to look into this fairly straightforward question and discovered that the polling data being published is quite superficial, painted in broad brushstrokes based on macro-regions – and even that is the best case. Let’s take the survey called “Ukraine in the Run-Up to the 2019 Presidential Election,” which was jointly run by three pollsters – the SOCIS Center for Social and Marketing Studies, the Kyiv International Institute for Sociology or KIIS, and the Razumkov Center – on January 16-29, 2019. No geographical information about the candidates was published at all. In three other polls – from the Rating Sociological Group’s “Monitoring the Electoral mood among Ukrainians: January 2019,” and KIIS’s “The Socio-political Mood among Ukrainians: January-February 2019, to the Razumkov Center’s “Trust in Public Institutions and the Electoral Orientation of Ukrainian Citizens” – information is only presented by macro-regions, which does not offer a complete in-depth picture.

What’s a macro-region? The Razumkov Center considers the “western macro-region” to be Volyn, Rivne, Lviv, Ivano-Frankivsk, Ternopil, and Zakarpattia Oblasts; KIIS adds Khmelnytsk Oblast to this mix. Yet voter preferences in these oblasts sometimes differ so radically that it makes no sense to lump them all together. For instance, Zakarpattia or Bukovyna have never voted the same as Lviv or Ternopil Oblasts. The same is true with the figures from Rating, but at least there’s a bit more specificity. The Western Region is separate from Halychyna, while the Center does not include the capital or the North.

RELATED ARTICLE: Round 1: A warm-up

Obviously more detailed data is available and perhaps it is made available for an additional fee. But then again, maybe it’s completely non-representative. For instance, a given poll does not capture all of Ukraine, only the major cities or individual oblasts, and that’s why it isn’t being published. In any case, generalizations always have room to maneuver in and to reduce the value of the data.

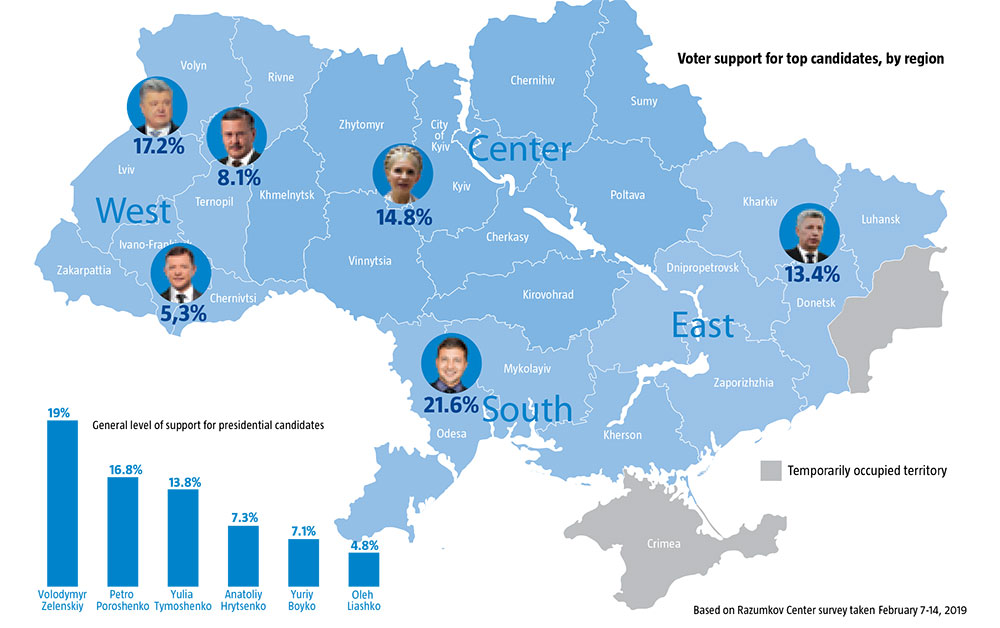

So, the leaders in the first round are Zelenskiy with nationwide support over 20%. Next is President Poroshenko, in the high teens. Third is Tymoshenko, not far behind Poroshenko but now trailing well behind Zelenskiy. Differences among the second echelon candidates are not especially significant: Yuriy Boyko leads in the mid-high single digits, with Anatoliy Hrytsenko close on his heels. Oleh Liashko is in the mid-to-low single digits and Andriy Sadoviy has now withdrawn his candidacy in support of Hrytsenko.

Let’s take a look at the picture geographically. The biggest support for Zelenskiy is in the South macro-region, in the mid 20s, with mid-high teens in the Center and the East. Even less support is coming from the West, where only one in seven would vote for him. Ironically, support for the comedian is lowest in the Donbas, which has been separated from the East macro-region, where only one in eight would cast their ballot for him.

In the West, Poroshenko is the frontrunner in the polls, with nearly one in six prepared to vote for him. He has the least support in the South, the East and the Donbas, where only one in 15-20 would vote for him.

Tymoshenko’s results are interesting, with one poll showing most of her support in the center and, somewhat less, in the West, with one in 6-9 ready to vote for her, down from a high of one in four, and least of all in the East, where only one in 13 support her. Strikingly, she has the least support in the Donbas, where only about one in 66 would vote for her, suggesting just how little love is lost for the gas princess in the war-battered region. Indeed, as Zelenskiy’s star has risen in the last month, Tymoshenko’s has slipped into third place.

Unfortunately, there is no information about whether the polls were run only in urban areas or whether rural voters were also tapped, as seems unlikely. And so it’s also hard to say who’s crazy about Zelenskiy in the South and East, whether its city votes or villagers who watch his show non-stop on 1+1 – or about Poroshenko in the West. But if we take a look at the history of all the previous presidential and even VR elections in Ukraine for the past quarter-century, the situation is actually a lot more predictable: no matter how much candidates claim that their support demonstrates demand for new faces in politics, it’s simply not true. The issue is rather different.

For voters in the East and South, Zelenskiy today is a bit like Leonid Kuchma in 1994, Communist leader Petro Symonenko in 1999, and Viktor Yanukovych in 2004 and 2010. He’s the comic reincarnation of the sovok, aka homo sovieticus. And his electorate is those who combine a soviet infantilism with post-bolshevism, people who haven’t adjusted to the rapid course of decommunization and still want to see a comeback for their primitive values. It may not even be clearly expressed “hammer&sickleness,” but a worldview based on “who cares what language” and “grandad fought in the war.”

Why does Zelenskiy have so little support in Western Ukraine? Because he’s a foreigner to them, in every sense possible. For one thing, the spirit of the kolhospnever was especially strong or ingrained in the region, people were less poisoned with it, and it has already been largely dispersed. The support for Poroshenko in this region is greater than anywhere else. Yet it’s not so much a matter that people there respect and adulate him, but that they don’t feel a need for “new faces.” Possibly even to the contrary. There was no love lost for Kravchuk 25 years ago, either, as a party ideologue, but they supported him against the threat that “Red Director” Kuchma represented, and later voted for Kuchma to prevent Communist Symonenko from winning. Indeed, however sentimental it might sound, Ukrainians in the western region, especially in Halychyna, always liked to see themelves as the country’s saviors. And they continue to sincerely fulfill this role.

As to the second-rank candidates, Boyko is best loved in the East, where one in 7-11 would vote for him. A whopping one in five voters are prepared to cast for him in the Donbas, yet less than even one in 100 in the West. In the West, Hrytsenko enjoys the support of one in 14, but he is disliked most in the East, where only one in 25 would vote for him, and in the Donbas, where the survey reported not a single vote of support. Liashko is a different case again: some polls give him about one in 20 votes in the East and the West – incidentally suggesting fruitful cooperation with Akhmetov – but only one in 30 in the South, while others show him most popular in the south, with one in 18 ready to plump for him, and least popular in the East, where only one in 35 would vote for him. Perhaps unsurprisingly, that same poll also showed Zelenskiy as the most popular in the South, suggesting that clowns will always find their fans there.

RELATED ARTICLE: What’s in a campaign platform?

According to a survey by KIIS, 78.6% of respondents reported that their main source of information about the candidates is television, while 35.0% also get information from online news sources, and 9.3% from social nets, where Facebook dominates by 82.4%. This actually provides a pretty good explanation of how ratings in this race are being shaped. Given that 1+1 was in second or third place for popularity among viewers in most regions over 2018, it’s easy enough to guess the secret of Zelenskiy’s success, after playing a fictitious president on this channel since November 2015, and why his rating is skyrocketing compared to other candidates. Similarly, most of the other channels, which regularly took potshots at the incumbent, whether deserved or not, but have now stopped presenting everything he does in a negative light, which has also contributed to some improvement in his rating. The internet and social nets are not so significant in this particular situation, but they do have a definite influence over voters. Moreover, this influence tends to be more destructive than constructive, given the informational chaos they tend to generate and the well-recorded tendency for people to live in “echo chambers” in social nets.

But the main thing that must be understand is that the immense flood of inconsistent data that is being poured into the ears of Ukrainian voters from all sources leaves them with a serious lack of unpolluted information. Access to the real situation is effectively blocked by garbage that makes it very hard to discover the truth. This makes it very easy to create myths and good people are covered in trash and turned into monsters, while the manipulators become heroes, stars and public favorites.

Translated by Lidia Wolanskyj

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook