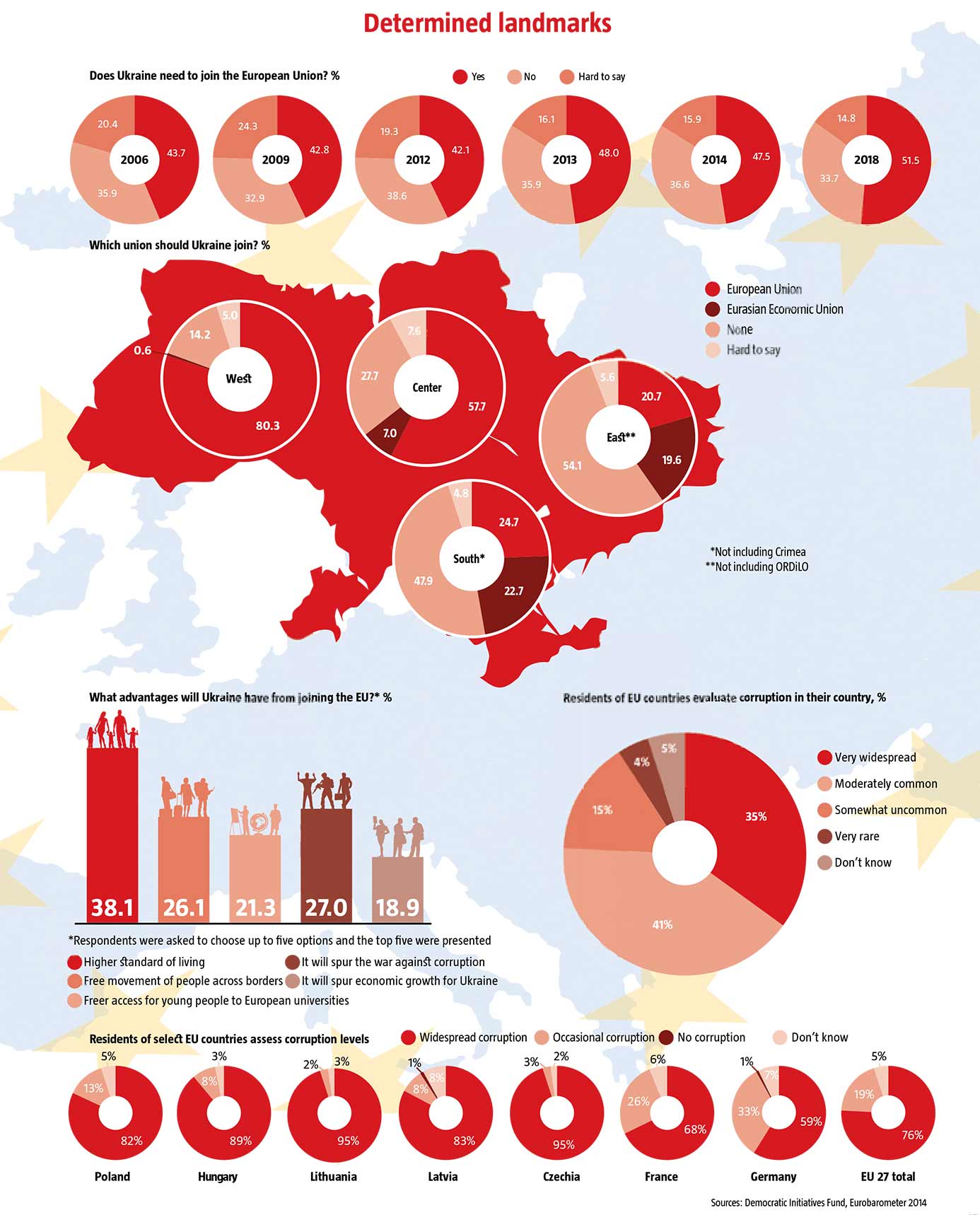

The Association Agreement with the European Union came into effect relatively recently, but questions about Ukraine’s foreign policy direction have long been treated as a done deal. Whatever the configuration of the government comes mid-2019, there will not be a 180-degree geopolitical switch, firstly because supporters of European integration among ordinary Ukrainians are a majority at 50.7%. Another 32.5% favor neutrality while a mere 10.9% still support the idea of joining the Eurasian Union under Russia, according to a 2018 Democratic Initiatives Fund poll.

However, history has shown that these positions can change significantly with just a change of circumstances. What’s more, current opinion polls don’t reflect the opinions of Ukrainians in the territories occupied by Russia, who are highly unlikely to be Euro-optimists. Still, it’s not just a question of arithmetic relativity. Pro-European aspirations, even with different ideological accents, have become a common feature for a very broad spectrum of social and political forces, from openly leftish-liberal to nationalist radical groups. Despite internal contradictions, sometimes to the point of open enmity, they affect not only the weary majority but also the current administration, which has to pay attention to them. This kind of potential cannot be seen in either the demoralized and marginalized pro-Russian camp, or among the supporters of “neutrality,” who tend to swing between both camps.

A philosophy of process

Most likely, the supporters of Eurointegration will slowly increase in influence while their opponents remain in the minority, not the least because of Russia’s ever-more-destructive position and its weakening influence in the region. In the longer term, however, things aren’t quite so simple. At its current stage, Ukraine’s Eurointegration is a philosophy of process rather than a philosophy aimed at an outcome, and that means that anything could happen in the long run. Of course, as long as the war with Russia continues – and probably for quite some time after it ends – there is little threat that pro-Russian attitudes will rise up again in Ukraine.

But that segment of society that is oriented on geopolitical neutrality could grow significantly, not just thanks to “russophiles,” but also among completely pro-Ukrainian Euroskeptics. Once it finds a political expression, the neutral position could well grow as a powerful alternative to the current mainstream Euro-optimism. Indeed, given the right circumstances, it might begin to overtake it.

RELATED ARTICLE: Pragmatic paternalism

In fact, as cooperation with the EU evolves, it won’t necessarily foster growing pro-European attitudes in Ukraine. As polls seem to suggest, the smallest proportion of Ukrainians who saw little to know advantages from membership in the EU was back in 2005 and 2007, when only 14 and 16% thought so. By contrast, 10 years later, the number of Ukrainians who thought so not only grew, but grew substantially, to 22% and 26% over 2015-2018, not far less than pre-Maidan levels – nearly 28% in 2011. The point is that it’s not just a matter of public opinion or to the political fluctuations that they might lead. What’s equally intriguing is the anatomy of Ukraine’s Euro-optimism, with the many nuances that could lead to a sharp rise in the opposite mood down the line.

The notion that Eurointegration represents Ukraine’s return to its civilizational home is generally popular and correct. However, the positive expectations of Ukrainians vis-à-vis the EU are basically quite pragmatic in nature. In August 2018, for instance, most Ukrainians tended to associate membership with a higher standard of living, with progress combating corruption, and with greater international mobility, especially educational opportunities, according to the 2018 DIF poll. Unsurprisingly, this largely coincides with the list of problems that Ukrainians also consider the most urgent: despite differences among polls, they are primarily concerned about corruption and economic woes – sometimes even more than about the war in the Donbas.

The fact that ordinary Ukrainians link the EU to a resolution of their day-to-day problems to a greater or lesser extent makes it possible for a pro-European camp to have a place in Ukrainian society. And so politicians from this camp do everything they can to support this idea, occasionally resorting to the kind of populism that is more associated with those who favor the Customs or Eurasian Union. Unfortunately, the more strongly Ukrainians connect a solution to their problems with one geopolitical vector or another, the more likely they are to be disappointed.

Growing international mobility as the country integrates more with the EU is clearly evident in statistics since visa-free travel was instituted and Ukrainians began migrating for work in large numbers to the EU. Still, a “European standard of living” is not guaranteed, even when Ukraine does join the EU. In the best-case scenario, the country is likely to lag behind its neighbors for some time to come. An even this level will have to be attained by tolerating difficult, unpopular and even painful reforms such as more expensive natural gas rates, the formation of a land market, replacing the archaic social security system, and so on. Eventually, these reforms will yield positive results, but Ukrainians don’t have a very large reserve of patience. At least this year, only 8% of them said they were prepared to tolerate a worsening in their own standard of living in order for reforms to succeed. Another 24% said they were prepared to put up with hardship for another year, while 60% said they were unwilling or unable to suffer any more, according to a 2018 DIF poll.

Thus, if Eurointegration doesn’t start giving positive results in the next while, public fatigue and discouragement will undermine not only politician’s ratings, but also the trust Ukrainians have in the European Union. Moreover, this is not just with respect to economic conditions but also, according to the same poll, to the war on corruption, which 79% of Ukrainians say is one of the country’s top problems. By contrast, only 55% say that the war in the Donbas is.

Modern mythology

It’s no secret that the battle against corruption is often carried out under the banner of “Europeanization,” which doesn’t sound very persuasive. This establishes a very seductive image of the EU as a sterile, corruption-free zone that, if we could only get in, would eliminate this horrible phenomenon forever. Reality is somewhat different from the imagined. For instance, in 2014 the European Commission evaluated the EU’s losses from corruption and came up with a figure €120 billion per year. Yet this figure turned out to be quite optimistic. According to a study by the RAND Corporation commissioned by the European Parliament and carried out in 2016, the cost of corruption ranges between €179 and €990 billion in the European Union.

Moreover, a European Commissions business poll in 2014 showed that 37% of business owners in EU countries said that they suffered from corruption while carrying out their normal commercial activities. In Czechia, this figure was 71%, in Portugal it was 68% and in Greece and Slovakia it was 66%. Indeed, 77% of EU residents believe that bribes and patronage were often the simplest way to get certain services in their countries. Meanwhile, only 29% believe that their governments were fighting effectively with corruption. There’s no question that this flies in the face of the image of the EU among many Ukrainians and the risk of this cherished illusion turning sharply into disenchantment in the future.

In addition, Ukraine’s Euro-optimistic circles aren’t homogenous and a split could happen not so much along nominally liberal and traditionalist line as between those for whom Europe offers a specific values- and rules-based matrix to which Ukrainian life should adapt, and those for whom it is the embodiment of some mythical older paternalistic dream of magical solutions to all problems. Metaphorically speaking, this is secondary paternalism, as these expectations tend to be transferred from the person’s own country, which already lacks sufficient trust, to foreign or supranational entities.

All jokes aside, 25% of Ukrainians think the West is the driver of reforms, while 28% are certain that it needs to be pressuring Ukraine’s government more, and only 9% are convinced that it is already doing enough, according to the DIF poll. Of course, for a certain part of the population, the so-called agents of change, the nominal West, especially the EU, is an ally in the struggle with those forces in Ukraine that are preventing the deracination of corruption and are interfering in reforms. Still, for most fans of Eurointegration, Europe remains largely what sovoks continue feeling nostalgia for in the USSR or Putinist Russia: an association whose membership brings well-being, stability and security. “European quality” instead of kovbasa with “GOST,” the soviet quality control stamp, “effective institutions” instead of “order” – in short, the form changes but the substance remains almost the same.

RELATED ARTICLE: Content, not form

Similarly, millions of Ukrainians accepted the market in the lat 1980s as an unknown lifestyle whose image was seen as a panacea to constant soviet shortages, impoverishment and burdensome leveling. Pragmatism was indubitably a stronger motivator in the 1991 referendum than any feeling of nationalism or patriotic idealism. Moreover, this is, generally speaking, quite natural and normal for any society. However, it’s worth remembering how enchantment with the market changed to sharp disenchantment when it turned out that the transition to the market could be very painful. Shocked by the dog-eat-dog realities of wild capitalism, Ukrainians were happy to listen to populists who promised to maintain free healthcare and education, a soviet system of subsidies and discounts, non-market utility rates, and other benefits of “advanced socialism.”

Something similar could take place again, not even that far in the future when Ukraine joins the EU, but even in the process of Eurointegration. In a broader historical context, this will bring on the next crisis on the way to a mature society. The question is whether the national elite, including the intellectuals, will be able to persuade Ukrainians in the need to continue moving towards Europe, only this time without illusions and unrealistic expectations. Either that, or the country will give into the counterarguments and plunge into the prison of populism, possibly pro-European in form but very much anti-European in spirit.

Translated by Lidia Wolanskyj

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook