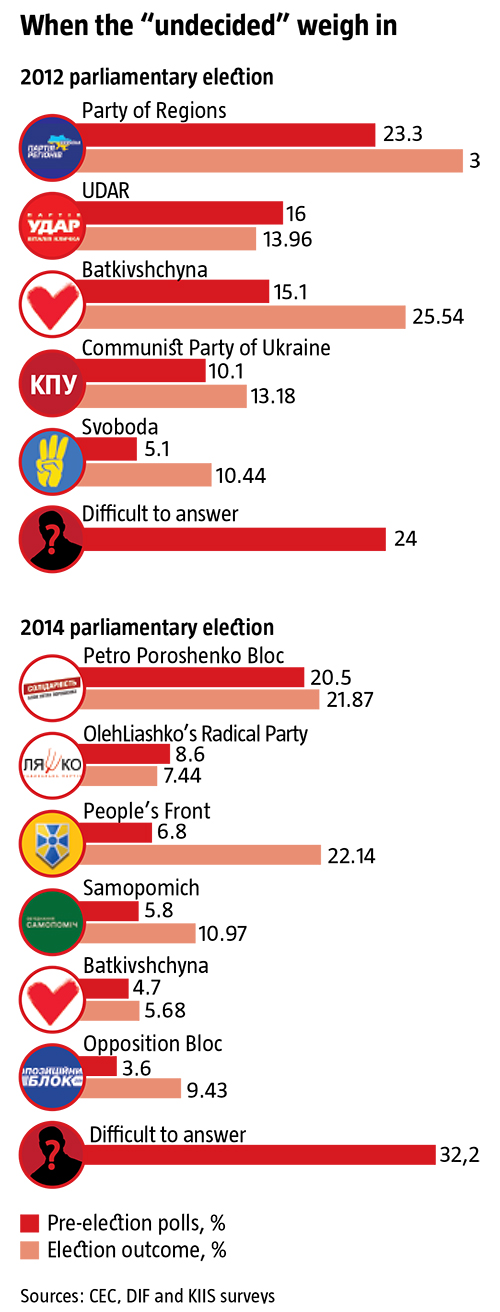

Candidates in the 2019 parliamentary and presidential elections will enter that year with poor support rates. According to pollsters, the most popular parties in Ukraine stay below 20% and all fairly visible political actors are mistrusted. This looks like a harbinger of a cut-throat political battle for every voter from the pool of those who have not decided on their choice yet. They are many of these.

According to a survey by the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology (KIIS), nearly 40% of Ukrainian voters were undecided about the upcoming elections as of December 2017. This share of the electorate may well bring an entirely new formation to power in Ukraine. The question is whether the 2019 candidates manage to get their act together and attract the support of this segment by the time the campaigns start. Given the current election moods, they will have to be enormously creative, and still have no guarantee of a positive outcome.

According to a survey by the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology (KIIS), nearly 40% of Ukrainian voters were undecided about the upcoming elections as of December 2017. This share of the electorate may well bring an entirely new formation to power in Ukraine. The question is whether the 2019 candidates manage to get their act together and attract the support of this segment by the time the campaigns start. Given the current election moods, they will have to be enormously creative, and still have no guarantee of a positive outcome.

Those currently in power are probably in the most difficult position. Ukraine’s voters blame on them all developments in Ukraine, as well as their own failed expectations accumulated during the Maidan and further fueled by the populism in 2014 elections. The extent to which those in power are actually at fault is open to discussion. However, it is public opinion that matters in elections. And that one is quite unanimous in Ukraine. According to the Ilko Kucheriv Democratic Initiatives Fund (DIF), 74% of Ukrainians believe that developments in Ukraine are going in the wrong direction. Trust for the President is at -62%, -65% for the Government and -56% for the Prime Minister. Less than 8% of Ukrainians are ready to vote for the parties in the nominal governing coalition – Petro Poroshenko Bloc and Narodnyi Front (People’s Front).

RELATED ARTICLE: Central Electoral Commission: A look at who will form the new team in the run-up to the 2019 elections

Those in power still have a strategic advantage – they have the real tools to influence life in the country and deliver positive results, of which there is only a handful. The few fulfilled promises include the Association Agreement and visa free travel with the EU. Those in power can also count the decommunization campaign as a success. However, these historic accomplishments will hardly have a decisive effect on the electorate: according to a survey by DIF, Ukrainians are actually most concerned about the war in the Donbas (75%), growing prices (50%), widespread corruption (47%) and poor social standards (42%).

Will those in power manage to meet the key demands of society before the elections? An economic miracle is not coming in the next year or two. The only thing the government can do over this time is to once again increase social benefits which will fuel inflation. And it will most likely bet on this social element. Having raised wages in 2017, the Government has again announced an increase of minimum wages to UAH 4,100. President Poroshenko and Vice Premier Pavlo Rozenko have made such statements. The Ministry of Social Policy has promised a 20% increase in pensions in 2019. This will likely win the sympathy of vulnerable social groups. The question is who they will thank for this bonus. The media have long been talking about tensions between the President and the Premier. One of the alleged reasons is Hroisman’s political ambitions and closer links to the People’s Front. If the conflict does erupt, Volodymyr Hriosman may be forced to resign in order to shed the negative legacy created by the previous economic hardships.

On other points, those in power will hardly manage to score. The top five priorities for the public include anti-corruption, pension, healthcare and law enforcement reforms, and lustration of officials. The reforms that had been widely announced in 2014 are stalling. According the DIF, a mere 5% of Ukrainians believe that they have been successful. 41% believe that nothing has been done to conduct reforms, while 35% put the progress at less than 10%. The President, the Government and the parliamentary coalition are named among the top five obstacles alongside oligarchs and law enforcement authorities.

It will be impossible to turn this public opinion upside down even if those in power fire a number of people, arrest officials involved in corruption and send them to court. Too many cases of impunity have accumulated over the past years, and a pre-election performance will hardly override them. The same goes for the rest of reforms — even if actually sped up in the run-up to the elections, they will not have a dramatic effect on the government’s negative image. The situation in the Donbas will also remain a sore spot as the war is unlikely to stop in 2019. The build-up of the Ukrainian army is the only argument that can partly override negativity in this aspect.

As a result, those currently in power are walking into the presidential and parliamentary elections with something in their hands but no tools that could change the electoral disposition to their benefit dramatically. Therefore, in addition to playing the social card, the President and coalition partners — provided that they don’t become total opponents by the time the elections arrive — will attempt to override negative information triggers by demonstrations of accomplishments and success. They will also try to mobilize the passive part of the electorate against their opponents. Obviously, Yulia Tymoshenko will be the main target of criticism. President Poroshenko has already slipped a mention of her one-time “friendship” with Vladimir Putin in his New Year address. This will not have much effect given how similar the rivals are in their ideology — or, more specifically, in the lack thereof. History tells us that Ukrainians best mobilize when opposite political paradigms clash, as in the rise against Viktor Yanukovych and the Party of Regions.

The current opposition in Ukraine is divided into three wings. The wing of the nominal national democrats includes Yulia Tymoshenko’s Batkivshchyna (Fatherland), Samopomich (Self-Reliance) led by Lviv Mayor Andriy Sadovyi, and a number of parties that are not in parliament.

The pro-Russian revanchists are represented by the Opposition Bloc led by Yuriy Boyko and Za Zhyttia (For Life) with Vadym Rabinovych. The nationalistic Svoboda (Freedom) led by Oleh Tiahnybok will have to share the electorate with the national-populist Oleh Liashko’s Radical Party.

Given the current level of public frustration with those in power, the opposition should feel confident. However, its rates are fairly low with little space for growth. The opposition’s main problem lies in the fact that its permanent leaders are mostly from the cohort of the  players of the past. None of them is actually capable of intriguing the voters as each has a trace of failures, controversial actions and scandals behind. All of them are more or less incorporated into the power system, therefore they are also to blame for the state of affairs in Ukraine.

players of the past. None of them is actually capable of intriguing the voters as each has a trace of failures, controversial actions and scandals behind. All of them are more or less incorporated into the power system, therefore they are also to blame for the state of affairs in Ukraine.

The opposition — or the nominally patriotic part of it — will thus try its best to find new faces as decor for their parties. New faces will pop up in the entourage of candidates for presidency who will thus try to cover up their own toxic reputations. Who exactly these new faces will be is still to be seen.

In 2014, party bigwigs were running for parliament behind a shield of military and volunteer commanders. Today, voters get far less carried away with people in fatigues. So the party players may now bet on socially active celebrities and anti-corruption activists.

As to the content of their politics, the only hope of the national democrats lies in getting more active in the media and criticizing those in power in the hope that the voters will choose “worse but different” in the end.

Nationalists will have a much harder time as they already risk returning to the status of an opposition that is beyond the margins of the system (or parliament). Representatives of this circle have no chance to win presidency. Yet, they will definitely try to increase their presence in the Verkhovna Rada. The first candidate is Svoboda with 3% of support today. Its unexpected success in the 2010 parliamentary election signals that it is still too early to write it off as an outsider.

When the rates are within the standard error margins, splitting up the electorate is unacceptable. Therefore, Svoboda, the National Corps and the Right Sector declared their unity by signing the National Manifesto in March 2017. Whether this agreement lasts through 2019 is unclear. So far, this strategy looks perfectly rational. Still, Oleh Liashko’s party can ruin Svoboda’s chance as it exploits a similar rhetoric and can steal a critical share of votes.

Given the experience of all previous elections, the share of ideologically engaged electorate in Ukraine is very low. Moreover, the nationalistic discourse has turned into political mainstream in the past years. De-communization, revival of historic memory and anti-Russian resistance — all the things that had once been a trick of the radical right — are now conducted on the nationwide scale under control of those in power. Nationalists will thus have to look for a different format of interacting with the voters and make sure that they stand out among their rivals. The liberation of Donbas is likely to be their key theme in 2019; on that, they will present themselves as feisty patriots, critics of the Minsk Agreements and of the “deals” made by those currently in power.

RELATED ARTICLE: Mistakes, unlearned lessons and consequences in the political confrontation between Ukraine's leadership and Mikheil Saakashvili

The core electorate of the radical right is concentrated in western regions. Therefore, this may work as the population of these areas that are more distant from the actual frontline is more reluctant to seek compromises. In addition to that, the radicals may take the niche of the street opposition and attract public attention with showy rallies which they tend to like and are good at. Overall, however, their political future is unclear.

By contrast to the nominally patriotic political forces that will compete for the voters in Central and Western Ukraine mostly, their ideological opponents will flirt with South-Eastern Ukraine. On one hand, this field has shrunk after the annexation of Crimea and the occupation of part of the Donbas. This rules out the prospect of a full revanche and restricts their space for growth. On the other hand, national democrats and nationalists traditionally ignore the “hopeless” regions, so they will not deal with the core electorate of the politicians with revanchist ambitions. The idyllic disposition of the revanchist camp is spoiled by the internal rivalry between the Opposition Bloc and Vadym Rabinovych, the leader of Za Zhyttia [For Life] party and the winner in this competition so far. According to DIF, Opposition Bloc’s Yuriy Boyko gains 7.7% and 12.7% in Southern and Eastern Ukraine respectively, and 3.6% in the Donbas. Vadym Rabinovych has 12% and 16.8% of support, and 17.9% in the Donbas. In terms of party support, Rabinovych is the winner, too. Za Zhyttia enjoys 10.9% in Southern Ukraine, 22% in Eastern Ukraine and 18.1% in the Donbas, while the Opposition Bloc has 7%, 13.4% and 9.6% respectively. Rabinovych’s success comes entirely from his feverish media presence, while the ex-Party of Regions players rely on local “authoritative” people in politics and business, and the political capital accumulated over the years.

Since South-Eastern Ukraine has the highest percentage of voters reluctant to participate in any elections or still undecided about their preference, the pro-Russian forces may try to consolidate and mobilize their electorate by offering a more radical rhetoric. They are likely to bring back the “threats” of NATO and Ukrainian nationalism, the status of Russian etc. as the mobilizing themes in their campaign. Also, the pro-Russian forces will probably act as the mouthpieces of the people who are weary of the war threat and support the fastest possible solution in the Donbas through a “dialogue” and “normalization of relations” with Russia.

Thus, there will be quite a few competitors for the undecided electorate. The current situation leaves no force in Ukraine’s politics confident of victory. Both those in power and in opposition have few chances of ending up with an electoral jackpot.

This is not because of a deficit of resources or creativity. This pre-election situation comes from failures by some players, and is a symptom of the biggest disease in Ukraine’s politics: the lack of rotation in its elite. According to a DIF poll, almost 67% of Ukrainians are looking forward to seeing new faces in politics. Ukraine’s political establishment is incapable of delivering this. Therefore, winning the trust and attention of the public is turning into an ever more daunting task. Unless the renewal of elite begins in the next few years, the consequences of this may prove surprisingly painful.

Translated by Anna Korbut

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook