In his first anniversary speech as President, Viktor Yanukovych announced that 2011 would be the last year that Ukraine had a land market in which legislation forbade the buying and selling of farmland. The President has kept his promise. Compliant deputies voted to cancel the moratorium on sale of farmland by 2015. According to Mykola Kaliuzhniy, Deputy Director of the State Agency for Land Resources, the Bill “On the land market” has been approved in the Cabinet and is now going to the Verkhovna Rada. If passed, Ukrainians will finally be allowed to buy and sell farmland. Experts claim that agribusinesses that currently lease land for peanuts could benefit the most from this, provided that another fundamental Bill, “On the state land register,” is also passed. Due by June 2011, this should make the official procedure for taking ownership of land easier.

Interest groups

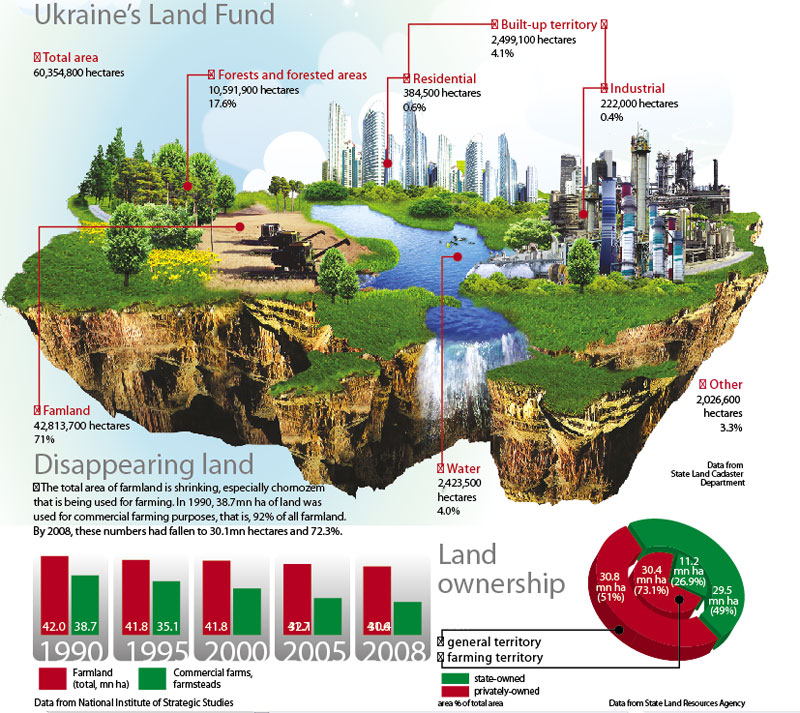

According to the State Land Committee, 15.91mn ownership certificates for all categories of land have been registered in Ukraine as of January 1, 2011, 15.41mn of them to individuals. Still, analysts claim that some 70 companies control 4.2mn ha of farmland, or 10% of all land in this category. For instance, Myronivskiy Khliboprodukt is exploiting 180,000 ha and Astarta-Kyiv has 166,000 ha. In 2010, 225,000 ha controlled by Illich-Agro merged with Rinat Akhmetov’s business empire after the Illich Steelworks was swallowed up.

Under current legislation, leasing fees can be paid in cash, in kind or in services. Official estimates are that nearly 60-70% of leases have been paid in kind over the past few years, mostly in the food grown—grain, vegetables, potatoes and oil—, or in services to landowners, including cleaning roads, plowing gardens, supporting village community centers, schools, social infrastructure, and so on. Experts say some lease contracts contain exotic benefits, such as death care, but those are rare.

Nice as that sounds, in fact, the annual income from an average plot of 4.1 ha is barely UAH 1,000-1,500. Often, landowners not only lease off their land for peanuts, but also work for the tenant.

Today, 60% of leasing contracts are for five years, but people are unlikely get their land back after these expire. Tenants have generally included a right of first refusal (RFR) clause in most contracts with the owners, thus ensuring the necessary basis for buying the land. Under current legislation, a single individual cannot buy over 100ha of land, but this is easy enough to avoid by registering ownership for an associated entity.

Fixing status quo

The Bill “On the land market” sets up things to legitimate the status quo. Art. 22 entitles tenants or users of land to a right of first refusal on a given parcel of land. Only the State can stand in their way, since it has the same preemptive right according to Para. 4 of this Article: “If several entities express the intention to exercise their right of first refusal…on a farming plot at the offered price, the State, represented by a specially authorized agent, shall be entitled to exercising this right on a priority basis…” This allows officials to actually block the purchase of any land plot quite legally. Some latifundia tenants will likely have “to share” with government officials in the process of getting land ownership, but that’s another story.

Ukraine’s land reform, especially its final stages, is beginning to resemble nothing so much as the voucher privatization of industrial companies. Back in 1999, when then-President Leonid Kuchma signed a Decree “On emergency measures to spur agricultural reform,” a certificate confirming ownership of a land plot became the key entitling document, identical to a voucher. In practice, though, the government never let landowners use their plots freely: it dragged out actual allocations, cut narrow plots and so on. What’s more, the official allocation was preceded by the Bill “On land leasing” on October 6, 1998, which encouraged widespread leasing of one-time collective farm lands.

Now, a little background: in 1999, 3.7mn ha of farmland were leased, compared to 29mn ha in 2000. The new Land Code implemented January 1, 2002, forced most landowners to lease their allotments: the State listed “improper use of land” as one of the grounds for rescind ownership. It became risky to let land lie idle. Yet, both then and now, some Ukrainians were physically unable to farm. According to the State Land Committee, 40% of smallholders are pensioners.

Official surveys suggest that one landowner in 10 is willing to sell his allotment. Yet, if the Bill “On Land Market” is enforced, the hope of selling it to any business without RFR could vanish. Firstly, the legislation will require a seller to notify, in writing, the tenant and the appropriate government office of the intention to sell the land and specify the price and other terms. Secondly, any entity that believed its RFR was being violated could sue the seller and demand that the rights and obligations of the seller be transferred. The provision will allow officials to appeal any purchase or sale transaction, including an allotment purchase by a tenant, since the Bill places the State higher than all other buyers of land.

Playing with numbers

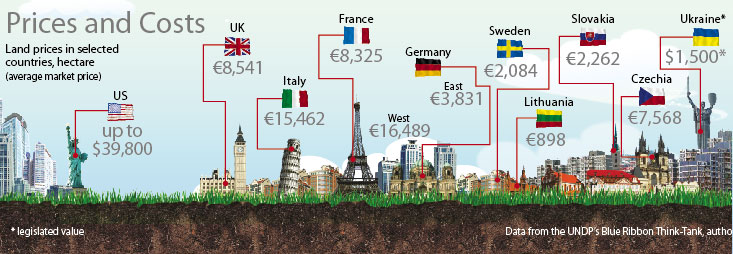

The Bill “On the land market” contains provisions restricting the free sale of land—essentially, free competition. On the contrary, they allow officials to abuse their positions and restrain demand for land even further. Moreover, these provisions are likely to knock farmland prices down. There is really no way to determine a fair price for black soil without a civilized market. The Land Union of Ukraine, which includes land allocation organizations, farmland assessors and farmers, claims that land prices today mean the cost of a lease traded by companies that buy and sell tenant firms. “One hectare of fertile land in a good location costs around US $200-600,” says LUU President Andriy Koshyl. “This price covers livestock, premises and all other items on the balance sheet. But it’s still only rent.”

In fact, the only benchmark is the minimum value set by the State Agency for Land Resources. In 2010, the Agency assessed one hectare of black soil at UAH 12,000, with plans to raise this to UAH 25,000 in 2011, or over US $3,000. Assessors claim this price is tentative, as some allotment are more expensive, for instance, if they are close to big cities, while barren land would be cheaper. Using the official value as a starting point, a parcel of 3,000 ha will cost UAH 75mn. Ukrainian farmers are unlikely to enjoy this kind of money from their turnover.

Moreover, tactically, renting land is more practical than buying it. “Lease contracts are already in place,” says a top manager of a large Eastern Ukrainian farm holding. “Our lawyers are working to extend them.” But owning land is strategically important for farming businesses. “Nobody will invest much in farming without being able to own the land,” says Mykola Vernytskiy, Director of Proagro, a farming consultancy. “One day, a landowner might say to his investor: I’ve found a different tenant. The average lease is five years, and in this kind of short term, tenants simply deplete the soil.” Owning land allows farmers to use it as collateral for a loan, increase capitalization—and use farming methods that are less destructive.

Official restrictions on foreign buyers reduce competition on the land market. “We have made sure that only Ukrainian citizens, and the Fund of State-Owned Land we’re about to set up, will be eligible to privatize farmland,” says the Land Resource Agency’s Kaliuzhniy, making no bones about their investment priorities. “Foreigners will be required to put their allotments up for auction within a year. For those who don’t, the Bill allows for expropriation.” The one loophole that will remain is that foreigners can still set up joint ventures.

In short, lifting the moratorium will hardly improve the well-being of rural households. Analysts say that land will sell well only near Kyiv and other major cities, where land prices plummeted 10 or sometimes 100 times since Fall 2008 after banks stopped handing out mortgages. Interest in land could change the category to construction for logistics centers, cottages and so on. Big agribusiness is not interested in allotments of 2-4 ha—an indication of how little Big Business thinks of the real landowners. This attitude, in turn, comes from legislation allowing thousands of hectares to be leased from rural owners for peanuts today while also allowing the lessee to snap it up wholesale, supervised by those same officials who are in charge of the land. Letting foreign players into Ukraine’s market, even just formally, could encourage domestic tycoons, to not only respect someone’s right of ownership, but also pay a more appropriate price for the land. Moreover, there are plenty of international mechanisms to prevent abuse by non-resident owners.

EXPERT OPINION

On protection

Andriy Martyn, Board Member, Land Union of Ukraine:

Andriy Martyn, Board Member, Land Union of Ukraine:

– Ukraine is regaining its role as a leading global food producer and we’re all proud of this. We understand this role will be extremely valuable over the next century. Agricultural holdings are an effective business. They can be sold abroad for a good price. But what’s left in the rural area afterwards? I guess the Anti-Monopoly Committee should have focused on land consolidation a while ago. Officials keep talking about protecting the rural population. But who is there to protect?… 80% of owners in Ukraine who were allocated land are either close to or beyond retirement age.

Leonid Kozachenko, President, Ukrainian Agrarian Confederation:

Leonid Kozachenko, President, Ukrainian Agrarian Confederation:

– Land ownership by foreigners is a touchy issue. Look at Brazil. Brazilian legislation allows foreign companies to own only 49% of arable land. There are many other things we could borrow from them. In 2010, investment in Brazil’s farm sector alone added up to US $22bn, with only 50mn ha in private ownership and 150mn ha potentially. And what do we have in Ukraine?… 35mn ha of farmland and US $40mn of investment. Just compare!