Prior to 1996, Ukraine was already effectively living under a new Basic Law. Constitutional amendments in the 1990s and the further constitutional process are not as widely known as the events of the “constitutional marathon” that took place all night in the Rada on June 28, 1996. To remind our readers of these events, The Ukrainian Week turned to Viktor Shyshkin, who was an elected MP first in the Ukrainian SSR and then in independent Ukraine, from 1990-1994. Shyshkin was a member of the VR Committee on legislation and legal provisions, as it was called in soviet times and even deputy chair for a time. The texts of all constitutional amendments went through this committee, which prepared them for the legislature.

A splintering Party

At the end of the 1980s, despite perestroika, Ukraine was governed by the Ukrainian SSR Constitution of 1978 with all the accompanying implications, starting with the notion of “scientific communism” and ending with the primary role of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) and the fact that USSR legislation superseded the laws of the republics. In 1990, the first relatively democratic elections to Ukraine’s soviet Verkhovna Rada took place. Although the majority was formed by MPs loyal to communism, called the 239 Group, opposition parties also gained substantive representation in the legislature and formed Narodniy Rukh or the People’s Movement.

“That Rada was the first whose members were elected on an alternative basis,” recalls Shyshkin. “A significant number of anti-communist and anti-imperial MPs appeared in the opposition. These were mostly people from the national-democratic camp, especially Narodniy Rukh, although there was also a Democratic platform within the Communist Party and anti-communist but pro-imperial deputies as well. However, even the pro-imperial anti-communists were not prepared to break away from the existing format at that time, as they understood that the only main enemy was the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.”

RELATED ARTICLE: Who wants a change of Ukraine's Constitution, and why

On July 16, 1990, the Verkhovna Rada issued its Declaration of State Sovereignty. This declaration announced to the world that Ukraine was independent in deciding any matters related to its existence as a state. It was about economic independence, the supremacy of Ukrainian law, its own Armed Forces and its own international relations. Still, the Declaration was not a law, let alone a Constitution, and the decision was made to give it added legitimacy by implementing changes to the soviet Constitution. “The Declaration of Sovereignty set the foundation for what later became amendments to the Constitution,” says Shyshkin.

Work on the Constitution wrapped up by October 1990. There was no dedicated constitutional commission at the time, according to Shyshkin, and the drafting was done through individual VR commission, now called committees. For instance, the economic and cultural commissions focused on those issues that were their remit. There was also a Commission for Legislative Provisions, which generally handled the institutional aspect—the gap between the judiciary and prosecutorial systems and the general soviet judiciary. Only afterwards, these adjustments were brought into line with one another to prevent contradictions.

Moscow’s waning supremacy

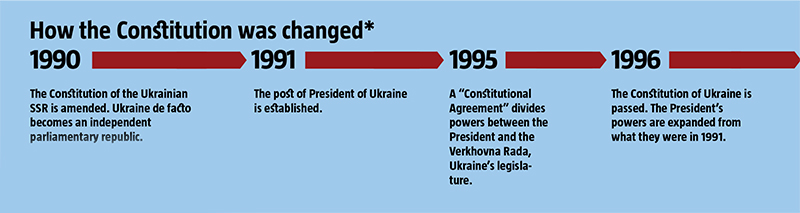

“This was mostly state issues, given that, in those days, the state had supremacy over the individual and they had to determine how state institutions were to work going forward,” says Shyshkin “All the propositions came to our Commission for Legislative Provisions and we were responsible for changes to the Constitution as a state document.” The number and scale of the changes to the Ukrainian SSR Constitution are similar to the adoption of the new Basic Law. They were voted on in the Rada on October 24, 1990. The irony was that the amendments took effect on November 7, October Revolution Day, the main state holiday in the USSR.

“In effect, Ukraine had declared independence undercover,” explains Shyshkin. “Because all of the republic’s institutions had become independent of Moscow and the Party’s managing role was null and void, although it was still in the Soviet Constitution.”

In addition, Art. 7 had been changed in October, with the provision on unions rewritten as an article on community organizations and a multi-party system. The section on the economic system, which designated the Ukrainian SSR economy as part of the overall soviet economy, was removed completely. One of the articles established the dominance of Ukrainian SSR laws on the territory of Ukraine and that soviet laws continued to be in effect in Ukraine only where they did not conflict with Ukrainian laws. It was now prohibited to send Ukrainian draftees to serve beyond the Ukrainian SSR. Finally, the Ukrainian Supreme Court became the highest court in the land and no longer sent cases to Moscow for review. Instead of a Constitutional Oversight Committee, the Rada announced that a Constitutional Court would be set up.

Shyshkin also points out that many changes were made to the prosecutorial system. “The Prosecutor’s Office was the only institution whose top officials were appointed directly from Moscow,” he explains. “We’re talking not even about approval, as it was with other agencies, but the actual selection and appointment. All the other top positions were appointed in Kyiv. Instead, the regional prosecutors of all the soviet republics and oblasts were appointed by the Prosecutor General of the USSR, and those prosecutors appointed all the local prosecutors, with the approval of the soviet PGO. The Prosecutor’s offices and the Defense Ministry, because there was no equivalent ministry at the republic level, were the two main pillars on which the empire stood. So we established the office of the Prosecutor General of the Ukrainian SSR, who was appointed by the Ukrainian legislature. So, on October 24, 1990, we became a constitutionally independent nation.”

RELATED ARTICLE: What it takes to upgrade Ukraine's military

In order for these changes to pass, the Rada needed to muster 300 votes, just like today. What helped back then was that the Communist Party of the Soviet Union was no longer a monolith but splintered along many lines: The communists included conservatives, like the ones who attempted the August putsch in 1991, and progressives, who either joined the People’s Council from the Democratic platform of the CPSU or simply supported the evolution of society, according to Shyshkin.

There was also a group of communists whom I would call ‘disciplined,’” he explains. “The concept of a state based on the rule of law first appeared in the CPSU’s Party documents during the 19th Congress. There, it was announced that the Soviet Union was transforming into a rule-of-law society. And so more Party documents appeared that were oriented towards this shift. Human rights became an important factor. In the 1978 Soviet Constitution, the word ‘person’ does not even appear, only the word ‘citizen,’ and so ‘human rights’ were presented only as ‘citizen rights.’ And yet human rights began to dominate when it came to making a rule-of-law state. That’s why the part of communists who were disciplined about enforcing Party documents was also in favor of change. They did not support the idea of a nation state, but they supported changes to the human rights aspect. Without them, we would never have been able to eliminate Art. 6.” That was the Article that established the top role of the CPSU.

The rise of the presidency

In 1990, the Ukrainian SSR was turning into a real, not just a nominal parliamentary republic, as before. The Verkhovna Rada now appointed the Government, judges and the Prosecutor General. The question of establishing a presidency had not been raised yet, but immediately came up in 1991, just before the final declaration of independence.

“At that time, the sense was that a parliamentary republic would not be good,” says Shyshkin. “As an example, they took the experience of France’s Fourth Republic, which was parliamentary, and proved ineffectual after WWII, then the French economy was in collapse and its colonial system still in place. The argument was that, at a time of major social and political upheaval, the country needed a strong, concentrated government. This was the foreign policy factor that made this concept dominate. In addition, its supporters believed that progressive democratic forces might gain the presidency.

“The thing was that Donetsk and Luhansk Oblasts were still voting for communists to the Rada almost exclusively,” Shyshkin explains. “By contrast, three of the 11 MPs from Kirovohrad Oblast were already members of the People’s Council, and two more favored it. The belief was that it would be difficult to overcome the aftermath of the soviet era through the legislature, whereas with a presidential form of government it would be doable. An authoritarian presidency was expected to work in favor of statehood.

“What’s more, this position was favored by Viacheslav Chornovil and a significant number of Rukh members, the Republicans and the Party of Democratic Revival of Ukraine,[1] to which I belonged,” Shyshkin recalls. “I wasn’t enamored with the idea and I pointed out that there were some risks. I wasn’t really a fan of a presidential republic in the way that it formed in Ukraine, just like I’m not a fan of the French model with its very powerful president. At the time, there were serious arguments in favor of a centralized government, as a temporary measure until Ukraine reached sustainable growth. The pro-imperial communists were against the idea of a president because they saw this as leading to the final collapse of the USSR, arguing that a single state could not have several presidents. There can be different structures, but not presidents.”

Shifting powers

In July 1991, the Verkhovna Rada voted to establish the post of president. The powers of the president that were bestowed on Leonid Kravchuk were narrower than those that were soon to be granted to Leonid Kuchma. For one thing, Ukraine’s first president did not nominate the Prosecutor or judges, and he needed the approval of the legislature not just to appoint a premier, but for a slew of key ministries. At the same time, says Viktor Shyshkin, it’s difficult to compare the powers of the different presidents: “You might say that the powers of the president in 1991 were somewhere between those in 1996 and 2004. In reality, it’s very hard to judge who of the presidents was actually weaker or stronger, Kravchuk, Kuchma or Yushchenko. They served in different legal and socio-political environments.

“During Kravchuk’s presidency, the Soviet Union fell apart and he had to build a state and its institutions, and to build relations with other countries,” he continues. “It really was the birth of a nation that subsequent presidents inherited. This is what was particular in 1990-1991. On a strictly legislative level, it’s impossible to compare them, because even the country’s laws reflected different social relations.”

The powers of Ukraine’s Head of State were significantly expanded already in 1995, with the signing of the “Constitutional Agreement between the Verkhovna Rada and the President.” This was part of the gradual shaping of the future Constitution of Ukraine. There were constant discussions about the way the country should be governed, the powers of the president, the economy, the foreign policy vector, and nuclear status—all of which had to be covered in the new Constitution. Added to that was the status of Crimea that was reflected in the Basic Law. In 1994, a new Verkhovna Rada was elected, but once again, no version of the draft Constitution made it even through the Constitutional Commission itself. At this point, the suggestion was made to have a temporary Constitutional Agreement that would clearly establish the powers of the legislative and executive branches of power.

RELATED ARTICLE: How Ukrainian politicians see the likelihood of elections in the occupied parts of Donbas

“I think that this is how we undermined the foundation of Ukrainian law,” says Shyshkin. “You can’t abuse the Constitution, no matter what the reasons. Some say that this was the only way out of a dead end. I don’t see that. The same governing structures remained in place, but someone was simply given more powers.

“There’s another point here,” adds Shyshkin. “Today, many Ukrainians talk about a social contract. But who’s supposed to agree to it with whom? It seems that there are disagreements even about this. We now have three possible approaches. The first one is that people agree among themselves about authorities, powers and so on. Typically this is done through a referendum. Second, the government agrees with the people. All our Constitutions have been based on this kind of an agreement: the government gave us a Constitution and the people agreed to it. The government has the right to do this as it is elected by the people and represents them.

“The third option is that those in power agree among themselves, Shyshkin concludes. “This is the worst scenario: the people don’t even count. The legislature negotiates with the president who they are going to divvy up something. That’s what the “Constitutional Agreement” was about and that’s why I’m dead against it. If we talk about a party to the agreement, such as the President and the Rada, then it’s obvious that the Rada has a lot more to lose from such an agreement.”

The rite of passage

In the end, a new Constitution was passed, exactly one year later, and the Agreement expired. Of course, the new Basic Law reflected the greater powers granted to President Kuchma that were eventually taken back by Viktor Yanukovych through the Constitutional Court.

“The Constitution enshrined the powers granted to the president in 1995,” says Shyshkin. “It was a compromise that lawmakers agreed to in order to get the necessary two-thirds vote: 300. And it most certainly was a compromise Constitution. Even a genius like Leonardo da Vinci couldn’t be expected to build a propeller like the one in his drawings because society simply wasn’t ready for it. The 1996 Constitution was a product of its times and I would call it a positive event. The question of language was a compromise; the issues of land, property and Crimea were all compromises.

“To some extent it was less ‘pro-presidential’ than the Constitutional Agreement,” notes Shyshkin. “Take the High Council of Justice. It had not been part of the Constitutional Agreement because the concept only emerged in the spring of 1996. The president is supposed to chair this Council, because it was based on the French model, where the president nominally chairs it although he doesn’t necessarily attend its sessions. The plan was that the Council would include 21 members, with the president at the head. This is the kind of thing I’m talking about. The Constitution was voted on article by article, and even sentence by sentence. During the debate of Art. 131, the president was removed and the Council was established with 20 members. Then the point was made that 20 was not divisible by 3, although different organizations contributed 3 members each. Then they voted for the PGO to contribute only two members. This was the kind of incident that reflected relations between the legislature and the president at the time: far from ideal and, unlike the current Rada, the 1996 Rada often challenged him.”

If not for the squabbles and disagreements in the Rada, the Constitution might have passed much earlier, says Shyshkin. Back in 1993, an official version was published in the press. There were other versions, too, whose general features were similar. “The communists, of course, did not have the office of the president,” Shyshkin goes on. “Their version was along the lines of ‘all power to the soviets [councils]’ and granted different status to the Russian language. Still, in terms of their constructive approach to the state itself, all versions were similar.” When the official draft Constitution was being drawn up, several thousand propositions, additions, changes and challenges were submitted.

RELATED ARTICLE: What makes Ukrainians vulnerable to populism

But what is not true is the myth that the Constitution was approved in a single night on June 28. “The Constitutional Commission, which had been set up again after the 1994 VR election, found itself in a stalemate and Vadym Hetman took the bull by the horns,” Shyshkin recalls. “Among the liberals, who at that point were in the majority, he was very highly regarded. Hetman announced that he was taking upon himself responsibility for setting up a working group to draft a final version of the Constitution. In this particular instance, the Speaker, Socialist Party leader Oleksandr Moroz, supported him. The group included representatives of all the factions and consultants, one of whom was me. By the end of May, if I remember correctly, we published the draft that went on to become the new Constitution.

“What’s more, we had been getting approval for bits and pieces of the previous two weeks as well,” says Shyshkin. “When they say that the Constitution was passed in a single night, it’s simply not true. Prior to that night, 40 articles had been approved over two weeks. Of course, these weren’t the most controversial articles, such as the provisions on the status of Crimea, the issue of ownership, and the language issue. Nevertheless, we managed to approve one quarter of the 161 articles in Ukraine’s Basic Law. The voting came for not just every article, but for sections, paragraphs and even sentences. If a sentence raised questions, then there might even be a vote over specific words. By June 28, mostly the articles on human rights and the electoral system had been approved. That night did, indeed, involve a kind of psychological breakthrough. As chair off the Temporary Special Commission Mykhailo Syrota took responsibility for the Rada on himself, declaring that he would be reporting ‘until the rooster crows.’”

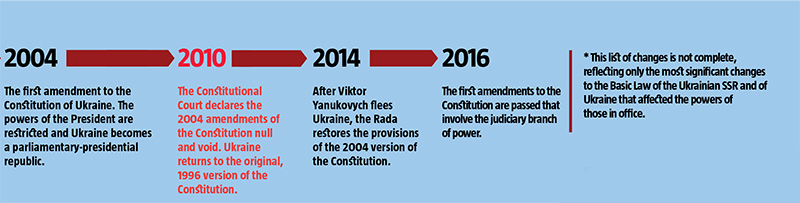

Since the Constitution was passed, Ukraine’s Basic Law has been amended five times, the first time coming 8 years later, during the Orange Revolution, in December 2004. Unfortunately, it’s hard to call the process of amending the Constitution transparent or consistent: many of them have taken place in emergency mode. As a result, the Constitutional Court declared the 2004 amendments null and void when Yanukovych came to office, giving him the expanded powers of the Kuchma years. After he fled in 2014, the Rada quickly reversed the Court’s decision and brought the 2004 provisions into force again. But there are no guarantees that these amendments will not again be declared unconstitutional at some point.

[1] The PDRU had been formed by the DemPlatform members in the CPSU.

Translated by Lidia Wolanskyj

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter or The Ukrainian Week on Facebook