Articles about how the convictions of Ukrainians have changed since the events of 2013-2014, dividing Ukraine’s history into “before” and “after,” appear with predictable regularity. One of the more obvious consequences is the maps that sociologists use when presenting their results: the labels “Northeast” and “Southwest” that divided Ukraine before have disappeared entirely. “The concept of a Southeast is already a myth,” pollster Yevhen Holovakha told The Ukrainian Week back in 2014. “At one time this made sense, based on electoral and political orientations. Now, everything has changed profoundly.”

Democracy vs authoritarianism

It’s three years and already the question arises, have the changes that took place been sustained, and where can they be seen? In June 2016, the Razumkov Center published a large-scale study of the changes in self-identification among Ukrainians called, “The identity of Ukrainian citizens under new circumstances: current state, trends and regional differences.” The study was based on a survey at the end of 2015 and a comparison with previous survey results.

One of the driving factors that led to the Euromaidan’s Revolution of Dignity was widespread anger at the use of force and the unwillingness of the Yanukovych regime to take the public mood into account in its actions. Afterwards, war began with Russia. Visits to news sites during the Euromaidan and at the beginning of the war broke all records. Because of this, Ukrainian society became highly politicized. A survey by the Razumkov Center showed that 12% of Ukrainians were very interested in politics and another 67% were somewhat interested. Only 21% were completely uninterested.

RELATED ARTICLE: Parliament Vice Speaker Oksana Syroyid on risks for Ukraine and the West in 2017

A majority of those surveyed, 51%, defined democracy as the most desirable form of government for Ukraine. But 18% were convinced that an authoritarian regime might be acceptable under certain circumstances and another 13% thought the question was meaningless. Still, the number of supporters of the idea of democracy has grown since 2012, when they represented 47% of those surveyed, and the number of those who favored authoritarianism was much higher, at 24%, while the share of those who were indifferent was 17%.

The share of those who favor democratic values has grown, despite noisy debates and even the occasional call for a “strong hand” to bring order under the current circumstances. Yet when asked to assess the current government, few noted serious changes. In 2012, at the peak of Viktor Yanukovych’s regime, Ukrainians gave the government a 4.97 points, where 1 is dictatorship and 10 is democracy, in December 2015 they gave the current government only 5.24 points.

The fading sovok

The pollsters decided to also look at the way Ukrainians understand the values of equality and freedom, the founding principles of democracy that are most popular in Ukraine. At 54%, the concept of “equal opportunities for every individual to develop their skills” was favored over the concept of “equal incomes and standards of living,” which was preferred by 36% of those polled.

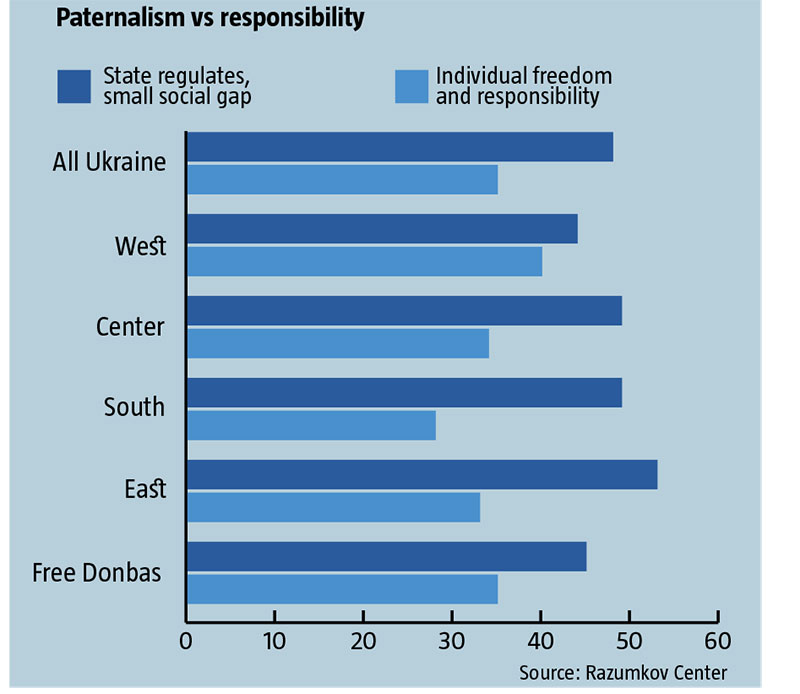

Still, more Ukrainians, at 48%, said they would prefer to live in a society where the government regulates everything but there aren’t major social gaps. Another 35% preferred a society with individual freedom, where people were responsible for and took care of themselves. The first of these indicators was seen as a reflection of a tendency toward paternalism in Ukrainian society that remains quite strong, even 25 years after the collapse of the Soviet Union. To some extent, this indicator flies in the face of the stereotype that western Ukraine is populated by “Europeans,” while the east is dominated by homo sovieticus or “sovoks,” as they are popularly called. The desire to hand over responsibility for a slew of areas in daily life is high across all regions, although the gap between the two indicators was a lot smaller in the West—44% to 40%.

In July 2016, Razumkov Center Deputy Director Yuriy Yakymenko commented on these results for The Ukrainian Week, saying that there was no reason to see this as some kind of catastrophe. “We aren’t looking for a ‘good tsar,’ that’s for sure,” Yakymenko explained. “The way to look at this is that more people would like to see their society organized as a democracy. As for this other aspect, we presented two questions. The first was to define whether equality meant equality of opportunity, in which the burden of using it is on the individual, or equality of material status. Most chose the first interpretation. With the second question, we asked what kind of society people would like to live in: in one with personal freedom but people taking care of themselves, or in a society where everything is regulated by the state, but there aren’t any serious social gaps. That’s a different situation. This is not quite paternalism, but rather the desire for the state to carry out a regulatory function to smooth inequalities.”

Yakymenko thought that these views were driven by the low standard of living among most Ukrainians and lack of trust in the state and its institutions.

Identity and self-pride

Overall, the Razumkov study encompassed a much larger period than just the Euromaidan, as it goes back to 2005, after the Orange Revolution. Changes in the identity of Ukrainians over the last decade are clearly substantial say sociologists. Among others, they noted the growing role of a national identity over a local or regional one, and a “growing sense of the value of one’s own country and a sense of self-respect for themselves as a nation, and an expanding Ukrainian national and cultural component in their identity, even in the East and South.”

What’s more, Ukrainians continue to take great pride in their achievements in sports, music, literature and so on. “So far, the political form of the state and socio-economic achievements still don’t offer enough of a source of pride,” the report notes.

RELATED ARTICLE: Persecutions of lawyers and activists in Crimea: goal, tactics

The authors are also cautious about drawing overly-optimistic conclusions about the present time: “The risk of conflict emerging within Ukrainian society and growing serious remains, based on noticeable differences among residents of different regions about the further geopolitical direction the country should move in. There are also serious problems connected to restoring Ukraine’s territorial integrity and the model of coexistence with those living in the regions that are currently occupied, how to reach reconciliation and mutual understanding.”

Ukrainians and the world

Various sociological agencies more-or-less regularly publish the results of their public opinion surveys. Many statistics are already freely accessible even for 2016, which is coming to an end. Of course, there is always a risk that data will be misinterpreted. To reduce this risk, this article primarily focuses on comparing the results of polls taken by one and the same organization commissioned by the same client. The purpose is not to evaluate the accuracy of particular results, as to see the trends. Sociologists warn that changes in the overall mood that are within 10% should not be treated as a serious trend as many factors can affect such a result. This is especially true when making comparisons across several years.

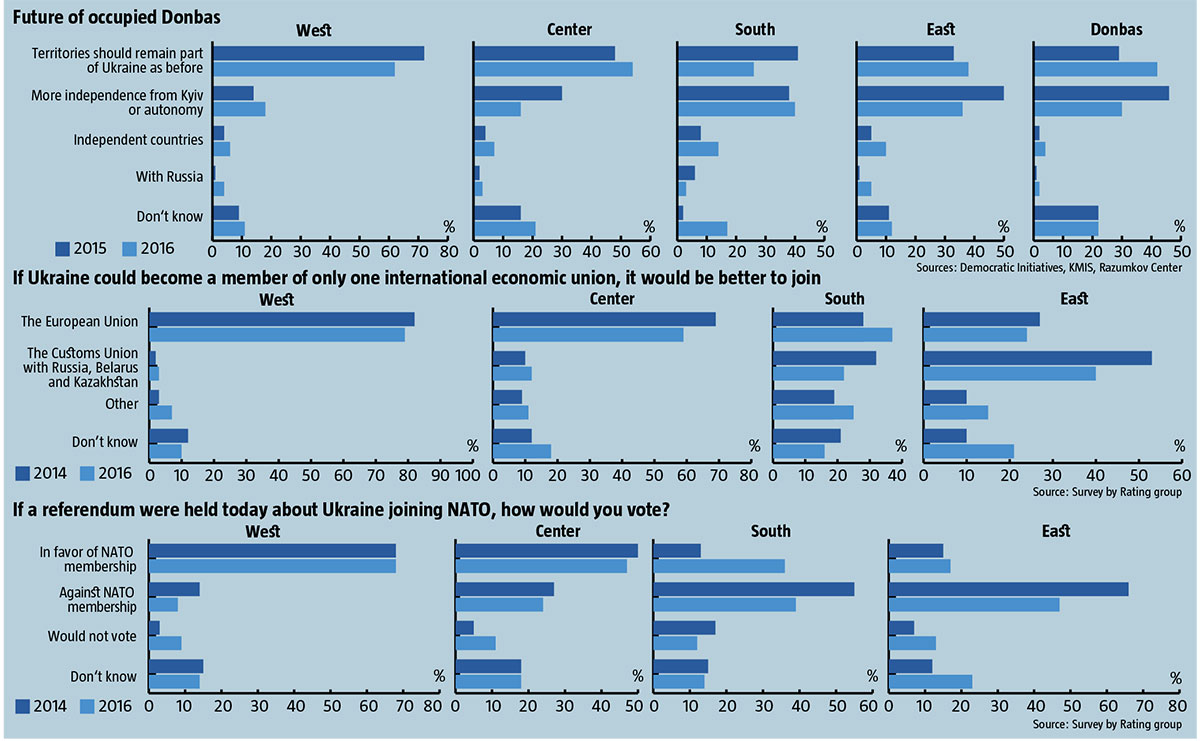

One of the direct consequences of the Euromaidan and Russia’s military aggression was a strengthening of the western outlook in international cooperation. Still, the prospect for integration with the EU appealed to Ukrainians before these events took place. The previous government played a not insignificant role in this by promoting its successes in preparing the Association Agreement with the EU. This was one of the pillars of Viktor Yanukovych’s strategy for being re-elected to a second term—a strategy that he himself wrecked when he suddenly altered Ukraine’s foreign policy orientation.

Joining the EU remains a strong desire among a majority of Ukrainians. In September 2016, 51% of those surveyed by the Rating Group put integration with the EU ahead of joining Russia’s Customs Union or some other association. Still, in Rating’s September 2015 survey, 57% of Ukrainians did so, and in September 2014, 59% did. This noticeable decline could be the result of a number of factors. For one thing, the Association Agreement did not have a noticeable impact on the standard of living of most Ukrainians. Many Ukrainians are also upset at what they see as the European Union’s limp response to Russia’s aggression against their country. And the way the granting of a visa-free regime to the EU has been dragged out for years and the obvious internal squabbles among the Union’s members have also left their imprint on Ukrainians.

RELATED ARTICLE: How sociologists interpret sentiments in Ukraine

Interesting that, according to these same polls for 2014-2016, while the popularity of the European Union has slipped in the West and the Center, it has grown in the South—although we should take into account that Dnipropetrovsk Oblast was shifted from the East macro-region to the South one.

The most striking and surprising changes that have taken place with the occupation of Crimea and the start of the war in Eastern Ukraine are the change in attitudes towards NATO and Russia. In the last two years, support for NATO among Ukrainians has grown steadily: in Rating’s poll, it went from 38% in April 2014 to 43% in April 2016, while those against have shrunk from 40% to 29%.

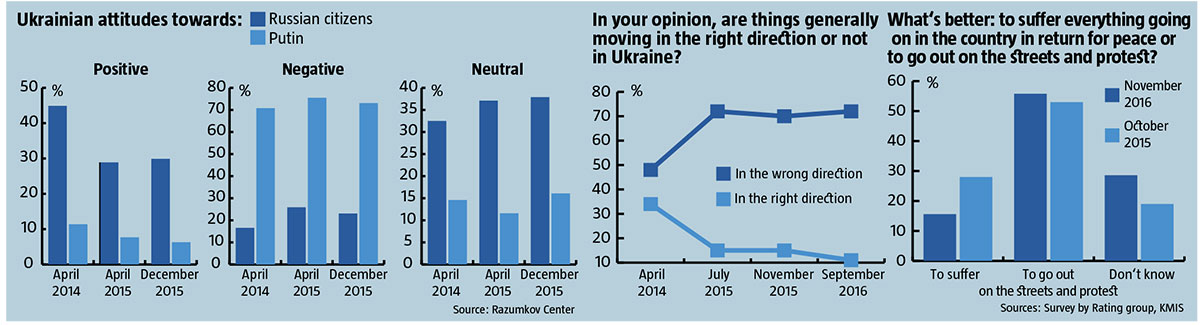

With Russia, the situation is not so obvious. Despite three years of war, Ukrainians still don’t equate the people of the Russian Federation with their leadership. In the eyes of many Ukrainians, the main, and often the only guilty party in this war is Vladimir Putin himself. The Razumkov survey, positive attitudes towards Russians among Ukrainians fell from 44.9% in April 2014, to 29.9% in December 2015, while negative ones rose from 16.6% to 23.1%. Only 6.3% of Ukrainians feel positive towards Putin, while 73.1% feel negative.

Similar attitudes towards Putin were seen in other sociological services. However, KIIS showed that between February and June 2016, attitudes towards Russia actually improved slightly. In commenting on these results, KIIS Director Volodymyr Paniotto said it was important not to connect this exclusively with the release of Nadia Savchenko, which happened in May.

“It’s possible that we are getting accustomed to the state of war, that it’s becoming routine, and so Ukrainian attitudes towards Russia are returning to their traditionally positive position,” Paniotto explained. “Still, in contrast to how this event was portrayed in Russia, the death of people in the East of the country is a constant, daily topic in all the news. Maybe Ukrainian media are reporting less on the presence of Russian soldiers in Donbas, especially rank-and-file, and so people are slowly connecting these military actions less with Russians than before. This would need to be studied a bit more.”

Problems at home

Gradually, we are seeing changes towards occupied Donbas as well. The Democratic Initiatives Fund (DIF) ran two polls in 2015 and 2016 in which respondents were asked about the future of DNR and LNR, the two pseudo-statelets. Nearly 50% in both surveys said that the territories should return to Ukraine in the same condition as before the conflict. Still, there were noticeable shifts in the responses between the two surveys, especially looked at from a regional perspective. In the West and South, fewer people were interested in returning to the pre-war status quo, while in the Center and East, more were. Among others, within a half-year, the number of those who believe in sanctions as a way to force Russia to sue for peace grew by 5% and this is by far the most popular response to the question of what pathways to peace would be best. The remaining indicators changed within the margin of error. Only about 15% of Ukrainians believe in resolving the situation by force.

At the same time, the number of Ukrainians who believe in the likelihood that a compromise can be reached that will satisfied all sides in the conflict slid from 54% to 47%. The number of those who believe in “peace at any price” inched up but not significant, as did the number of those who, on the contrary, are convinced that peace will only come if one of the sides wins. Depending on the situation, more than 50% of Ukrainians support a partial or complete isolation of the occupied parts of Donbas.

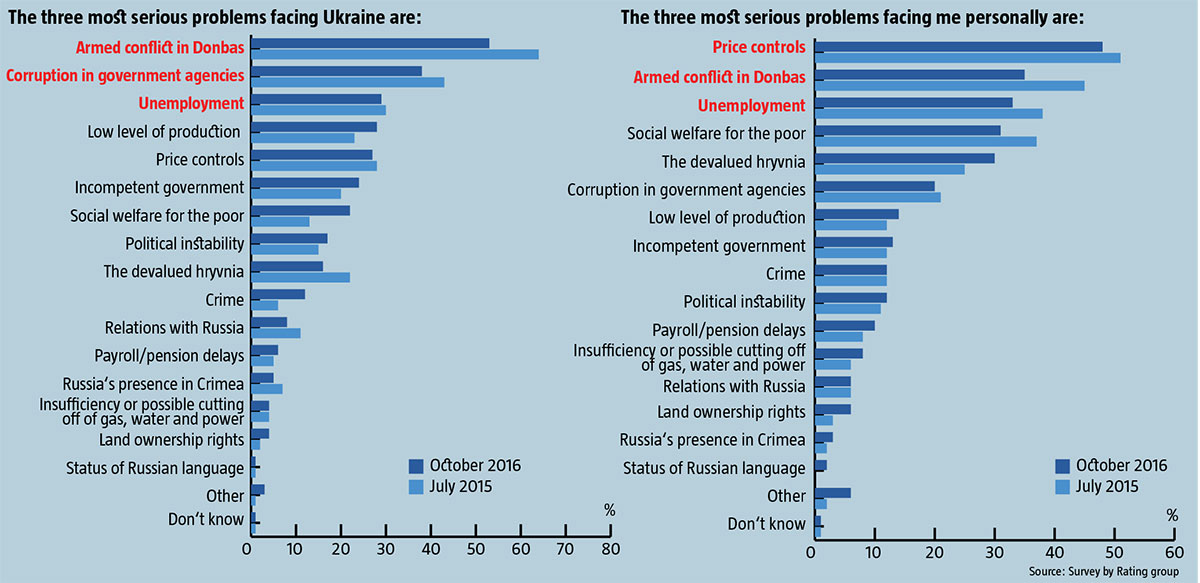

An indication that Ukrainians may have somewhat lost interest in the war in Donbas can be seen in the way they prioritize the most important problems facing them, an issue that the Rating Group monitors. In their survey, they ask respondents to name the three most important issues facing Ukraine and, separately, those facing them, personally. The armed conflict in Donbas always ended up in the top three. However, whereas the war remains the #1 problem for the country as a whole, in the personal ratings, Ukrainians ranked it only third. Moreover, the number of people ranking it at the top shrank from 63% to 53% between July 2015 and October 2016 for Ukraine as a whole, and from 45% to 35% for themselves personally.

Among other issues that Ukrainians keep bringing up are corruption in government agencies, unemployment and rising prices. Among the problems facing the country, Ukrainians are more often bringing up social welfare for the poor, the low level of industrial production, and crime. Among personal issues, they name the devaluation of the hryvnia. Clearly, these responses are tied primarily to economic adversity.

One attitude in Ukrainian society that does not seem to change is continuing lack of trust in public institutions. Three years after the Revolution, the government and its agencies have not managed to improve people’s perceptions of them. Double-digit ratings—albeit below 20%—of complete trust are enjoyed only by the volunteer battalions, the church, volunteers and the Armed Forces. According to the Razumkov Center, there is a difference between the way Ukrainians perceive the “old” militsia and the “new” police: the former enjoy complete trust among only 2.5% of Ukrainians, while the latter enjoy it among nearly 8%. The leaders for complete lack of trust, leaving out elected bodies and the Government, traditionally remain the courts, the government bureaucracy and the prosecutor’s office.

Still and all, Ukrainians aren’t prepared to suffer just anything just to maintain peace and order in the country. According to various surveys, more than 50% of them are more than prepared to take to the streets again rather than suffer. Moreover, the number of Ukrainians who are convinced that the country is moving in the wrong direction has nearly doubled since the Euromaidan. Under the circumstances, the lack of big demonstrations on the downtown streets of various cities is not a reflection of the wisdom of those in power but the lack of a clear and understandable reason to protest—and the eternal hope of Ukrainians that things will get better, after all.

Translated by Lidia Wolanskyj

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook