OBITUARY

“On 20 July, after a long struggle with illness, dissident and one of the founders of the 1960s’ Ukrainian samvydav[1] passed away.” such are the short announcements of the death of Vasyl Lisoviy online and in daily newspapers. However, they miss some of the key aspects of his life. Vasyl Lisoviy was one of the most moral participants of the 1960-1980s Resistance Movement and one of the most thorough and deepest Ukrainian philosophers of the late 20th century, when he finally had the freedom to write and say what he thought.

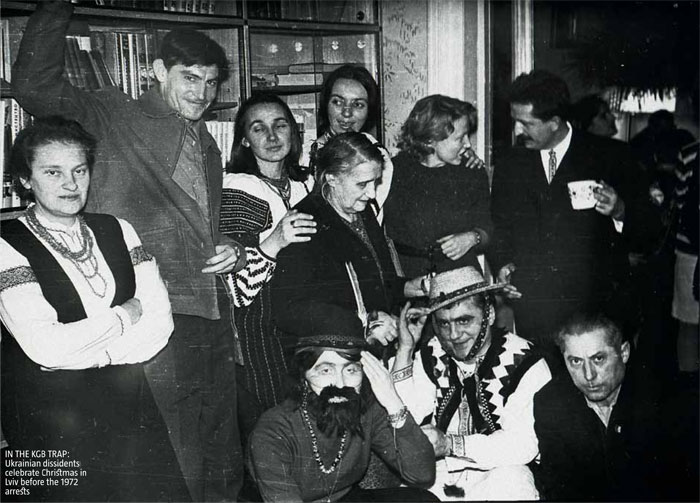

His life was the path of a man who did not simply search for the truth, but strove to live according to it. Born to a family of farmers, he graduated from the Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv with a degree in History and Philosophy, he subsequently become a Professor and Senior Fellow at the Philosophy Institute. Meanwhile, he actively wrote and distributed self-published literature from the early 1960s on. Then came 1972, when Ukraine saw a wave of arrests to completely eliminate the “nationalistic virus” once and for all. The arrests did not touchVasyl Lisoviy, while many others switched to the other side or hushed up, finding a compromise with the system. Together with Yevhen Proniuk, Vasyl Lisoviy issued the 6th edition of the self-published Ukrayinskiy Visnyk (Ukrainian Newsletter) to publicise information about those arrested and try to challenge the accusations against them of publishing previous issues. Later, he wrote an Open Letter to the Members of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine, in which he gave judiciously and reasonably substantiated arguments as to why the soviet system could not lead countries to progressive development and the inevitability of its degradation and collapse. In the end, after a devastating critique of the lawlessness of all cases against the Ukrainian intelligentsia, Vasyl Lisoviy demanded that the system arrest and judge him as well, because the reprisal against them was “aimed at the living Ukrainian nation and the living Ukrainian culture.” The response from the system was immediate: 7 years of labour camps and 3 years of exile.

Serhiy Hrabovsky

The Ukrainian Week presents Vasyl Lisoviy’s investigative memoirs about the repressive techniques used by the KGB against the activists of the 1960-1980s dissident movement in Ukraine.

The protocol of a case that was part of the political repression campaign in the USSR, or the written testimony of the accused, or any other related documents, say nothing about the condition of the person whose words were written therein. Readers or researchers can only guess at what stood behind his/her unexpected switch to side with the prosecution. A lot has been done so far to research the red terror, executed through its key tools, such as the Cheka, the Extraordinary Commission; the State Political Directorate abbreviated as GPU in Russian; NKVD and MGB, the Ministry of State Security or soviet intelligence agency in the 1940-1950s. But the scale of their crimes against humanity is only now being gradually revealed. In their introduction to Cheka-GPU-NKVD in Ukraine, a book published in 1997 in Kyiv, its authors Yuriy Shapoval, Volodymyr Prystaiko and Vadym Zolotariov note the necessity to create “the conceptual, factual and resourceful basis for further research.” Even though this need refers to the operation of these units in Ukraine, most major documents are stored in Moscow, if not destroyed. The fact that the GDR Stasi destroyed their archives proved the system’s fear of what might be revealed if these documents are declassified. I don’t think that the KGB would pass up the opportunity to clean up their archives of the most dangerous documents in the early 1990s.

As for the KGB, there is enough evidence to characterise the most important aspects of its activity in the 1960-1970s. In 1959, the Presidium of the Communist Party’s Central Committee approved the Provision on the KGB under the USSR Council of Ministers. It said that the KGB “reports directly to and is controlled by the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.” Its key responsibilities, other than foreign intelligence and the discovery of spies and saboteurs, included the struggle against “the hostile activity of anti-soviet and nationalistic elements in the USSR.” In 1967, a range of special units were merged into the notorious Fifth Directorate, created to eliminate “ideological dissent.” Needless to say, the introduction of these minimum legal restrictions proved to be a positive step – at the very least, an element of legitimacy.

As a result of these changes, physical torture in cells was cancelled, although with some exceptions, so enforcers resorted to concealing continued tortures. The KGB found it easier to hide its complicity in various forms of physical torture, including violent beatings, in camps, disciplinary cells and prisons, than in detention centers. But in the mid-1960s, its treatment of dissidents during investigation was brutal. It secretly forged politically motivated charges and used provocations. Only some of these forged cases have been disclosed and made public so far (Vadym Smohytel, Mykola Horbal, Vasyl Ovsienko and others). Murders, both abroad and in the USSR, could still be committed, but only under the guise of special operations. Moreover, not all such measures were taken under written orders. Additional evidence is needed to say accurately how exactly, and for what purpose the KGB applied extreme measures, such as torture and murders, after the mid-1960s. One such case was the brutal murder of Alla Horska[2] (the likelihood of KGB involvement in it is very high). It may have been an attempt to intimidate the entire dissident movement in Ukraine. But these were exceptional measures, executed “on the spot” with no relevant instructions being put on paper.

Thus, the KGB became an entity that wanted to preserve its “façade” of a show legitimacy (and that’s good enough) while hiding all of its dirty laundry in the shadow. It took into account the naïve frankness of various orders and instructions from party bosses and Cheka people of the Stalin era in the operation of the repressive machine that used words, such as “contaminate”, “discredit”, “provoke” and others. The introduction of elements of legitimacy required staff with legal training, therefore the KGB ranks were gradually joined by people, unwilling to take on the position of a “hawk”. This mirrored similar trends in party structures. But in the KGB, as the military branch, the disparity between moderate and radical views was less clear than in the party.

Moscow dictated all important decisions, primarily those related to personnel. One example was the removal of Petro Shelest (First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Ukrainian Communist Party in 1963–1972 who was inconvenient because of his Ukraine-oriented position, even despite two waves of dissident arrests during his time as leader of the Ukrainian SSR – ed.). Another was the replacement of Vitaliy Nikitchenko, a “softer” chief of the Ukrainian branch of the KGB, with the tougher Vitaliy Fedorchuk in 1970. Ideologists struggled to spread the idea that the series of tough punishments in Ukraine was the result of locals “going over the edge.” Meanwhile, they consistently removed any party or repressive authority boss who did not prove determined enough, especially in fighting against “nationalists.” In Ukraine, the so-called “overstepping of boundaries” resulted from the fact that any chief or director down to the head of a kolkhoz, who was not tough or violent enough, inevitably not only lost his position, but also faced the risk of being repressed as a saboteur or malingerer. The Kremlin dictated the scale and toughness of verdicts in proceedings against Ukrainian dissidents.

No party or Cheka functionary wanted to leave “traces”. Most “dirty” cases that were beyond the boundaries of formal socialist legitimacy were classified as “operative work”. It is difficult to assess the dark side of the KGB’s operations now, because the documents that were not destroyed are still in classified archives. This is especially true of the KGB’s technical executive department, established in 1959 and made up of a range of special units. What investigations, other than wiretapping and secret murders, were conducted for the purposes of this department? How many people worked on secret programmes at various research institutions? Even those who cooperated with the KGB on a voluntary or forced basis are reluctant to disclose information they know today because of the secrecy surrounding its executive or operative activity. I think their fear for their personal security is justified.

Today, we have a pretty good description of the KGB’s repressive tools against the dissident and Helsinki movements in the 1960-1980s in the testimony and memoirs of dissidents and the research of historians Heorhiy Kasianov, Anatoliy Rusnachenko, Yuriy Shapoval and others. They range from “soft” to the most violent and extreme tools. The categories include preventive and educational measures – the “persuasion” mostly being limited to warnings, threats and the application of some “tools of influence”; involving staff in public discussions on cases at committee meetings or through reprimands made at work; discrediting; measures related to significant areas of life, the stake being a job, education, getting an academic degree or an apartment, the opportunity to publish one’s writings or art and threats against family members, especially children, and friends, etc; preventive arrests; imprisonment under criminal charges, including those resulting from provocations; imprisonment under political charges; sending people to asylums, as well as crippling and murder.

COLD ISOLATION: Ukrainian dissidents in exile to the Komi Autonomous Republic

At that point, the communist regime was twisted in convulsions. Neither the social nor the national aspects of the dominating ideology could withstand even the most primitive criticism. The bourgeoisie as a class, i.e. the owners of production facilities, no longer existed. The idea of the impact of “bourgeois ideology” on the youth brought up in the communist system was not convincing either, as that same youth included some leading figures in the dissident movement, such as Ivan Svitlychniy, Vyacheslav Chornovil, Ivan Dzyuba, Ivan Drach and others. The regime faced its major defeat at the level of “preventive conversations” regardless of who conducted them. The “educational campaign” already beginning in kindergarten and primary school can brainwash people, but as soon as critical thinking awakens, the effect of the brainwashing is ruined. A crisis in ideology signals that its arguments lose their power of persuasion.

Leonid Brezhnev’s coming to power was the nomenclature’s attempt to rescue its dominating position, achieving “stabilization” by reviving more determined repression, aimed at crushing the dissident movement. The verdicts that were much tougher for Ukrainian dissenters compared to those anywhere else in the USSR, were first and foremost caused by the national element: the loss of Ukraine, albeit in the future, would be the most painful blow to Russian imperialism.

When I later looked at dissidents’ different interpretations of KGB activities, I found some inconsistencies. For one thing, they tended to underestimate the KGB’s professionalism in using various practices and tools to fight against the regime’s opponents. On their part, Western special services seemed to be quite naïve about the methods and techniques of the KGB, just as they were about the role of scientific and technical developments at the relevant units of soviet special services. If Bohdan Stashynsky[3] had not outfoxed the KGB (by escaping to the West and explaining how he assassinated Stepan Bandera at trial), the scenario whereby the leader of OUN, the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, died of a heart attack would probably still be held to be the truth.

This is not to say that the concept of “the KGB knowing everything” which Cheka members tried to spread to intimidate dissenters, would be helpful to the dissident movement. But I found it surprising to hear someone sharing stories of their visit to a detention center and assuming confidently that all detention centers were virtually the same for everyone else. Aleksandr Bolonkin[4] once published an article about his previous imprisonment at a press-cell[5] in Ulan-Ude. Without this, my experience in the same circumstances would have remained unique. In my opinion, it is inconsistent to assume that the KGB only crossed the boundaries of formal legitimacy behind the walls of a detention center or that it did not resort to illegal actions against people cut off from the world in a detention center.

Everyone who judges another prisoner’s behaviour under conditions of complete isolation, based on his or her own experience, makes the tacit assumption that the KGB complied with general procedures. However, my personal experience does not confirm this far too optimistic assessment of the implementation of legal restrictions by the KGB. I acknowledged a certain evolution in the KGB’s operation since the late 1950s and did not consider all Cheka employees to be fanatical executors of their bosses’ will. Still, I never underestimated the KGB’s array of tools and professionally trained staff.

Compared to the terror of repressive structures that preceded the KGB under different names, a new obvious threat surfaced: physical tortures were replaced by attacks on nerves and mental health. The crisis of official ideology encouraged the idea that psychiatry could help in the situation. It was not a new idea, as witnessed by the history of repression since the coming to power of the Bolsheviks suggests. The idea of qualifying all dissidents as unable to adjust to the social environment offered new opportunities. This strategy was theoretically confirmed by several leading psychiatrists in Moscow (see Soviet Psychiatry. Misconception and Agenda by A. Korotenko and N. Alikina for more details). This side of the KGB’s scenarios continues to be classified. Possibly the most demonstrative example of the use of psychiatry as a tool against dissenters by the communist special service, was the large-scale “purging” of Kyiv of ideologically unreliable elements before the 1980 Olympics. Some of them, mainly dissidents, were placed in psychiatric hospitals.

I would like to note that qualifying dissenters’ actions as a type of mental disorder was in line with the “sound reason” of those who failed to understand any ethically motivated activism because it contradicts the primary life interests of its performer. If a person overcomes the fear that signals a danger for it, then is he/she is acting under the influence of hidden or even subconscious incentives, albeit hiding them (even if intuitively) behind ethical arguments. Thus, such person must be guided by a “super-valuable idea” as indicated in the “diagnosis” of Petro Hryhorenko, a soviet general who in the 1960s, stood up for Crimean Tatars and other peoples deported by the Stalin regime, or some sort of subconscious motivation is concealed behind these ethical arguments. People who never risked their comfort, let alone life, for ethical reasons, saw such actions as a manifestation of abnormality.

In the 1960-1980s, the KGB consisted of pragmatic cynics rather than the fanatical followers of Lenin, therefore their “sound reason” was guided by this concept. Meanwhile, ethically motivated moves fueled hidden jealousy, irritation and resentment in some people: this was another source of their tendency, often subconscious, to discredit such activism and libel it, coming up with all sorts of hidden motives that may have guided the activists, such as insults, envy, the pursuit of glory, pride, personal life, etc. In the eyes of a materialist, ethical idealism is seen as something false, hence the consequence of mental disorders.

[1] Samvydav translates into English as self-publishing or grassroots publishing, used by dissidents in the former Soviet Union to evade official censorship.

[2] Alla Horska was a Ukrainian painter and activist from the generation of shestydesiatnyky or the 1960s dissidents. She was killed at her father’s-in-law apartment in 1970. Officially, the investigation found that her father-in-law murdered her because of personal dislike and then committed suicide. Even though authorities hushed up talk about her death, it caused an uproar both in Ukraine and abroad.

[3] Bohdan Stashynsky is the KGB assassin of Ukrainian nationalist leaders Lev Rebet and Stepan Bandera

[4] Aleksandr Bolonkin is a soviet/American scientist in aviation, space, mathematics and computers. The KGB arrested him in 1972 for the distribution of works by Sakharov and Solzhenitsyn. After 15 years in camps and exile, he was released and sent abroad in 1987. After that, he taught at American universities, worked as a senior fellow at NASA and US Air Force research laboratories

[5] In Russian prison slang, a press-cell is a means of torture whereby a prisoner is put in a cell with hand-selected criminals who exert psychological or physical pressure to break the person.