The 130th anniversary of Lypynsky’s birth went quietly unnoticed in Ukraine. Meanwhile, as a political thinker and historian, he is of paramount importance and relevance to present-day Ukraine. Our political establishment would be well served by following his recipes for building the Ukrainian state and society.

The Ukrainian revolution of 1917-18 showed that the Ukrainian elite had insufficient state-building potential, evidenced by the collapse of Volodymyr Vynnychenko-style radical social demagoguery. Lypynsky offered a different recipe for constructing what he called a classocratic society, one of producers (producer-owners) and creators of settled European culture.

TERRITORIAL PATRIOTISM

Lypynsky contrasted social peace with class struggle, social revolution, and the power of the crowd over the individual. “We lost the armed struggle but we will not lose Ukraine if we can recruit both the wealthy and poor to the idea of a successful Ukrainian sate,” Lypynsky stated. There is no irreconcilable social antagonism between the poor and the rich. On the contrary, there is common interest in the prosperity of their country. In contemporary terms, Lypynsky was a champion of the middle class.

Ukrainians have been trapped with the image of themselves as a peasant nation since time immemorial. Lypynsky formulated a postulate of territorial patriotism that served as the prototype for a political nation that unites people not so much by ethnicity as by common territory. Ukrainian territorial patriotism can be readily embraced by both indigenous Ukrainians and other ethnicities living in Ukraine such as Poles, Russians or Jews. According to Lypynsky, the main thing is that the union be rooted in the Ukrainian cultural matrix.

He was one of the first to promote Ukrainian culture to a dominating position in the country. He started his career as a Polish-speaking writer but wrote his first work in Ukrainian already in 1908 and was recognized as one of the most prominent Ukrainian political writers by the time the First World War began. His Lysty do brativ-khliborobiv (Letters to Brothers-Agrarians, 1926) alone bears testament to his outstanding talent as a thinker.

AN ADVOCATE OF ARISTOCRATISM

Lypynsky became a spokesman for Ukrainian elitism. Here he consciously went against the flow and stood nearly by himself in the circles of the democratic and people-loving intelligentsia that abandoned its “landlordship” and forever lost faith in the need for higher social strata in the Ukrainian cause. He did follow the track trodden by his predecessors, including his teacher and mentor Volodymyr Antonovych. The latter called on the Polonized Ukrainian nobility to return to the people and become declassed. Lypynsky believed that it had to remain what it was but become Ukrainian, serve the cause of national revival and participate in the political life of Ukrainian circles.

Before Lypynsky, the image of a nobleman had a clearly negative connotation in the Ukrainian milieu. However, after his Z dziejów Ukrainy (From the History of Ukraine) came out in 1912, the educated public learned that the Bohdan Khmelnytsky movement was spearheaded by the Ukrainian nobility – it was the brains of the liberation struggle. Khmelnytsky, Stanyslav Morozenko, Mykhailo Krychevsky and Ivan Vyhovsky were noblemen by their social origin, which, it turned out, did not prevent them from sensing and expressing authentically Ukrainian political interests. They had a much deeper understanding of social tasks than did rank-and-file Cossacks who were not concerned about strategy and the fine nuances of political agreements. All these things were in the care of the Ukrainian nobility, which traditional Ukrainian historiography left outside the scope of the Ukrainian nation. However, its representatives worked out policies for the Hetman State that maneuvered between two powers, Poland and Muscovy, in the second half of the 17th century and were the masterminds behind all agreements. They were great champions of Ukraine’s political interests.

The Polonized Ukrainian nobility, rather than descendants of Ukrainian Cossack officers who joined the ranks of the Russian nobility in the late 18th century, launched the national revival in the modern age by calling for a cultural border between what was Russian and Ukrainian. Antonovych, Tadei Rylsky, Osyp Yurkevych and Kostiantyn Mykhalchuk, rather than ethnic Ukrainians that hailed from the former Hetman State (such as Vasyl Tarnavsky, Volodymyr Naumenko, Oleksandr Lazarevsky and Orest Levytsky), became the first champions of independence. Why? Because all things Ukrainian were never alien to them. Moreover, they remained an indispensable part of their mentality. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, the experience of the Polonized nobility became the most valuable asset of national political thought, considering that these people were brought up in the spirit of statehood-oriented thinking.

Lypynsky was the first to call on his fellow countrymen to accept, rather than reject, the contribution of the Polish-Ukrainian cultural environment in the border regions to the national cause. He urged Ukrainians to integrate it and make it their own. He opened for Ukraine an entire Atlantis of seemingly foreign, but actually Ukrainian, culture. Even Hetman Mikolaj Potocki, a Uniate and the biggest magnate in Right Bank Ukraine in the 18th century, had certain Ukrainian sentiments. Lypynsky expanded the horizons of Ukrainian mentality and offered Ukrainians a broader view on their political tasks. He considered these tasks in primarily political, rather than ethnographic-cultural terms.

THE STATEHOOD INSTINCT

Lypynsky was among the first champions of the idea of an independent Ukraine. Lypynsky, rather than Mykola Mikhnovsky or Yulian Bachynsky (who wrote the first programs for the establishment of an independent Ukrainian state), created an ideology for a Ukrainian state, which he conclusively formulated in his Letters to Brothers-Agrarians only in 1926, when the liberation struggle had already ended.

He became a spontaneous separatist back in his lyceum years when he cooperated with the Revolutionary Ukrainian Party and the Polish Socialist Party at educational institutions in Lutsk, Zhytomyr and Kyiv. To Lypynsky, a man of Polish revolutionary milieu, nothing was taboo when it came to the issue of independence: it was a totally natural phenomenon to him. The Poles had no illusions regarding autonomy and federalism in the Russian state: it was either an independent Poland or Russia in its place. Lypynsky and his ideological followers possessed that same statehood instinct regarding Ukraine’s future.

They viewed the subsidiary nature of the psyche of Ukrainians living in Dnieper Ukraine and the universalism of the Orthodox world they inherited in an almost genetic fashion as factors that made Ukraine permanently dependent on Russian Orthodoxy and Russian autocratic rulers. Russia’s influence produced in them a theoretical dualism: Russia’s longtime political domination of Ukrainian lands versus the struggle to preserve local cultural features. This doomed symbiosis led one generation of Ukrainians after another to recognize the full victory of Russian cultural space on Ukrainian territory. To the “Polish” Lypynsky, this political division fortunately did not exist. Several years prior to the First World War, he turned down Yevhen Chykalenko’s invitation to become the chief editor of the Rada newspaper. The reason was that, although a convinced separatist, Chykalenko sought to deflect in every possible way public accusations of separatism hurled by Russian politicians against the Ukrainian movement. Rada consistently affirmed its federalism and loyalty to the Russian state. It never adopted a clear position of this “separatism” or defined Ukrainian national priorities. “We need to train Ukrainians to be independent and assert their normalcy, that is, if they want to remain Ukrainians rather than turn into ‘Rus’ people,” Lypynsky wrote.

He was the ideological mastermind of the Young Ukrainian movement, when a number of social democrats and social revolutionaries departed from social democratic ideology and set up a non-partisan separatist group called Vilna Ukraina (Free Ukraine) in 1911-12. It became the prototype of the later Union for Ukrainian Liberation.

Precisely this kind of non-partisan understanding of liberation efforts aimed first at establishing an independent state and then solving other social problems was lacking among the leadership of the Ukrainian Revolution in 1917-18, which led to its defeat by the invading Russian Bolsheviks. Lypynsky was one of the few Ukrainian politicians who viewed the problem of Ukrainian state building through a European, rather than Eurasian-Russian, lens.

Diplomatic service : Viacheslav Lypynsky with members of Ukrainian Embassy in Vienna, 1918

A UKRAINIAN CENTER-RIGHTIST

Lypynsky’s social philosophy should not be simplified or categorized under specific ideological labels as it is in most scholarly works. It is a mistake to identify him only as a champion of the Hetman State and the mastermind behind the Hetman movement, even though he should be credited for the bright political image that Pavlo Skoropadsky enjoys. Lypynsky politically “Ukrainized” Skoropadsky when the latter was already in emigration by editing his memoirs and creating an image of an enlightened Ukrainian monarch. Lypynsky was, above all, a conservative politician and producer of rightist and centrist social values. He left the Ukrainian Agrarian Democratic Union because he disagreed with its narrow politics and instead set up a brotherhood of statehood-minded classocrats.

His later statements on socialist parties earned him a reputation as an extreme opponent of the national democratic movement. But in reality it was more complicated than that. He supported the general democratic movement before the revolution and viewed right-wing national forces as an integral component. He coordinated his actions with the national democratic leadership (Mykhailo Hrushevsky, Serhiy Yefremov and Borys Hrinchenko) and was also friends with Levko Yurkevych and even Vynnychenko, trying but ultimately failing to change the latter’s political views. He had an original interpretation for the behavior of Myron, the protagonist of Vynnychenko’s scandalous work Shchabli zhyttia (The Steps of Life), perceiving him as a déclassé severed from traditional society. But in 1917-19, Lypynsky became deeply disappointed with the Ukrainian left when it failed miserably to establish a Ukrainian state. This caused him to level caustic criticism against them.

A CONSERVATIVE ALTERNATIVE

Unlike Ukrainian socialists, Lypynsky believed that the state had to be built not by a crowd, an anarchic revolutionary mass, but primarily by wealthy people who had economic leverage. At the time, this leverage was held by the Russian nobility, as well as Polish landlords and the bourgeoisie. Thus, Lypynsky was convinced that landowners and entrepreneurs had to be recruited to the Ukrainian cause and persuaded that an independent Ukrainian state was an advantage. Rather than being estranged from the Ukrainian nation, they had to be recognized as Ukrainian citizens to the same degree that peasants were. Only then, he argued, would the territory they owned—and their consciousness—become Ukrainian. “In order not to drown in Moscow by pulling ourselves away from Poland or in Warsaw by separating ourselves from Muscovy, we must show a different center of gravitation,” Lypynsky wrote. Kyiv was to become such a center, he believed.

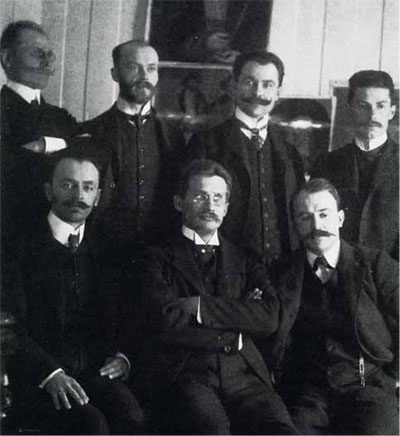

In academic circles: At the convention of Ukrainian historians and painters in Zakopane, 1908

In contrast, Vynnychenko and the majority of Ukrainian socialists followed the recipe written by the Russian Bolsheviks. According to this approach, any union was class-based. A landlord was always an enemy, they believed. Friends had to be sought among the “disadvantaged”. So the Russian proletariat appeared to be much closer than Ukrainian peasantry.

This “medicine” was deadly for a nation without a statehood instinct. Red Moscow rid itself of the old elite but recruited its representatives to public service. The leading communist stratum was made up of former members of the Russian nobility, bourgeoisie and Jews who were in strong opposition to the old regime. Raised in the spirit of respect for their state, they were Russian patriots and adopted a condescending attitude toward non-Russian nations. They prioritized the social over the national. Now, according to Lypynsky, one of the preconditions for an independent state was the will to have it and the willingness for uncompromising struggle to win it. These thoughts remain as relevant today as they were during Lypynsky’s lifetime.

BIO

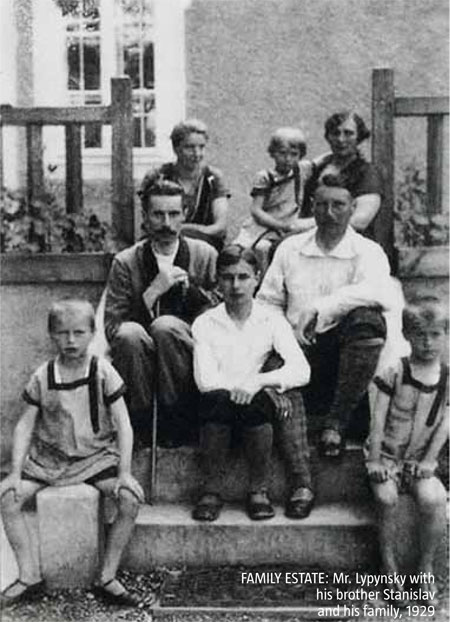

Viacheslav Lypynsky (1882-1931) was born in a noble Polish family in Zaturka, a village in Volyn Oblast. He went to gymnasiums in Zhytomyr, Lutsk and Kyiv, and studied at Jagellonian University (Krakow) and the University of Geneva in 1903-1907. In October 1917, he co founded Ukrainian Agrarian Democratic Party of and worked as the Ambassador of Ukraine and Ukrainian People's Republic (UNR) in Vienna over 1918-1919. After emigration, he established the Ukrainian Union of Agrarians and Politicians in 1920. Viacheslav Lypynsky died on 26 April 1931 in Austria. His works include "The Nobility in Ukraine: Its Role In the Life of Ukrainian People and Its History" (Krakow, 1909), "The Calling of the Varyags or the Union of Agrarians" (1925), "Religion and Church in the History of Ukraine" (1925) and "Letters to Brothers Agrarians" (1926).

LEGACY

In 1960s, V.K. Lypynsky East European Research Institute ( EERI) was established in Philadelphia. Initiated by the then director Ivan Lysiak-Rudnytsky, the Institute launched the publication of Lypynsky's works in 25 volumes. After Ukraine gained independence in the early 1990s, Professor Yaroslav Pelensky, the Institute's last director, transferred it to Ukraine where it has been operating as the Intitute for European Studies under the National Academy of Sciences wer since. During the past few years, the new administration has been ignoring the key objective of the Institute that is to publish all of his works, correspondence and archive documents currently stored at the Ukrainian Catholic University in Rome and remain mostly unavailable for researchers. So far, only one third of Lypynsky's legacy has been published.