Russian authorities are busy seeking new sources to revive the economy and to avoid profound reform.

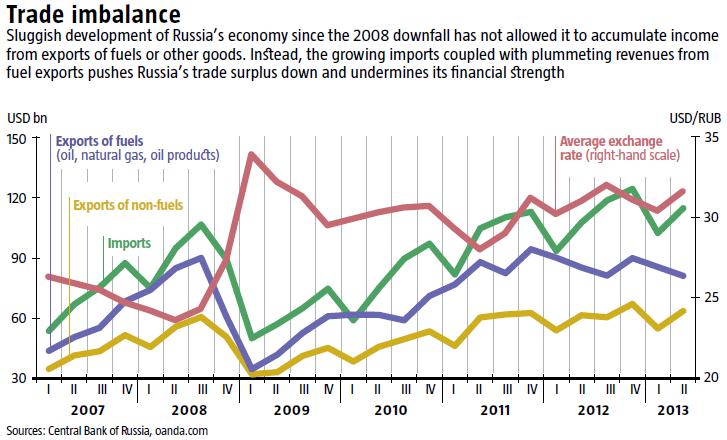

Unlike Ukraine, Russia is much less dependent on exports. Over the past year, its share in the Russian GDP was 28%. However, it excessively depends on exports of fuels that accounts for over 16% of GDP and 58% of total exports. Stagnation of physical amounts of fuel exports and falling prices pushed exports down in H1 2013. Meanwhile, imports rose 7.9% in H1 2013. As a result, Russia’s trade surplus is declining (see Trade imbalance).

This would hardly be a serious problem if Russia had been using its oil dollars more effectively. However, most of this cash ends up abroad instead of being invested into the nation’s economy.

Firstly, money is massively pumped out into offshore zones. The top three recipients of most direct investment from Russia are Cyprus, Netherlands and British Virgin Islands. According to the Central Bank of Russia, Russian FDI stock there amounted to USD 225bn or 65% of total overseas investment as of the beginning of 2012. Capital outflow exceeded USD 30bn in 2012. Some of this money returns to Russia as investment but most will stay abroad. Meanwhile, Russia’s own economy remains cash-starved.

Secondly, a lot of capital flows into the shadow. Russia’s Central Bank has long been monitoring obscure transactions of settlements for fake imports or securities that are actually worthless.

READ ALSO: Is Gazprom on the Ropes?

Finally, Russia intentionally spends a share of its oil revenues to reinforce its influence in the world. Its financial sector (Central Bank is not taken into account) has accumulated almost USD 300bn worth of receivables from non-residents, half of this after the 2008-2009 crisis. This money is used to issue loans to other states, including Ukraine, and expand Russian banking chains abroad. It thus receives political dividends in these countries in exchange for keeping their financial sectors afloat instead of investing into its own economy.

If this last and Russia’s trade balance continues to shrink, the Russians will either have to revise their oil dollar splurge policy or go through yet another increasingly painful crisis caused by every drop in fuel prices.

PUBLIC FINANCE AND BANKS

Russia’s consolidated budget heavily relies on revenues from the oil and gas industry. In H1 2013, they shrank 3.3% compared to the same period of 2012. Despite current budget surplus and financial reserves accumulated earlier, this stagnation has some painful side effects. The Kremlin’s policy is based on high social benefits. This splurge is financed through the budget (wages, pensions and social benefits accounted for 51% of consolidated government expenditures in H1 2013) and low taxes (basic personal income tax is 13% in Russia. This is one the lowest rates in the world). As a result, the Russians have been enjoying relatively high social standards that kept growing. Over the past four quarters, however, pensions have seen a minimum increase while prices grow almost as fast as wages do. This signals that the Russian government is adjusting social spending to the energy market. So far, the growing social benefits have kept the Russians away from massive opposition and protests. This may change if nominal pensions and salaries stop growing and devaluation of the ruble as a result of Moscow’s reluctance to tighten its belts eats up most of people’s income.

READ ALSO: Oliver Bullough: “There will now be much fewer Russians than we used to have in the world”

Meanwhile, a big share of the Russian budget goes to state administration, defence, security and law enforcement. In H1 2013, it accounted for 24% of all expenditures. Obviously, part of this is spent to support Russia’s influence abroad. Plus, the Kremlin will hardly scrimp on keeping order and peace at home. However, the plummeting budget revenues may force Russia to choose between quitting some of its zones of influence abroad and decreasing funding for them, or cutting social benefits at home and spending more to crush the resulting protests.

In this situation, banks would normally feed the economy. However, they are busy expanding their presence abroad and investing more into that rather than into supporting companies at home with credits. As a result, domestic demand in Russia is entering a stagnation that may soon grow into a recession.

THE REAL SECTOR

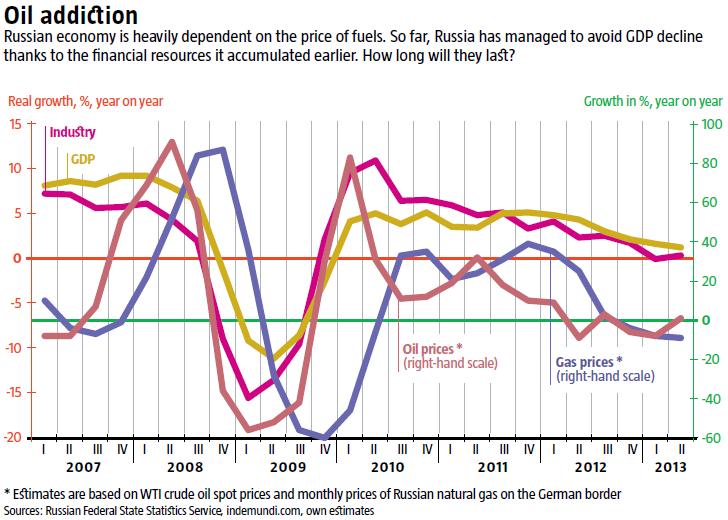

All this has already affected the real sector. In Q2 2013, GDP grew a meager 1.2%, and industrial output has been shrinking (see Oil addiction). Recession in the Russian economy has not begun yet, but some details signal that it will. Big and medium enterprises in virtually all industries reported a 23% decline in income in H1 2013. This affects productivity, profitability and competitiveness of most of Russian business.

Stagnation in cumulative demand has hit construction. Real gross value added the industry generated in Q2 2013 dropped 3.9% compared to the same period in 2012. This trend in construction reflects a decline of investment. A drop in the production of investment goods coupled with stagnation in the production of consumer goods has caused a 1.3% decline in the processing industry output year on year. Albeit insignificant, this figure continues the slowdown trend that started in 2012 and may aggravate further on.

A steep rise in fuel prices is Russia’s only chance to resume brisk economic growth, but it is unlikely. Instead, Russian economy will likely see a further decline which will show how ineffective and reform-hungry it is. The Kremlin does not want to admit this. Perhaps, it is afraid since any transformations of the economic system now will inevitably lead to a growing middle class which will demand changes and threaten the stability of Putin’s regime.