Ukraine’s agricultural sector has seen rapid development over the past few years. This has boosted agricultural investment, mostly from oligarchs who have recently turned to it, probably having realized that the potential of the other industries they had been milking, such as steelmaking and mining, engineering, pipes and others, is almost exhausted.

Farming is one of the few businesses in Ukraine that can still quickly generate windfall profits – something the oligarchs have always pursued – provided that it has a favourable environment. It’s no wonder that once businessmen with close ties to the government took an interest in farming, the latter began to support the agricultural sector, declaring that it should become a new driver for economic growth and a solution to many macroecomic problems. But this priority could actually prove devastating for both rural areas of Ukraine and the economy as a whole.

DOWN-TO-EARTH IDEAS

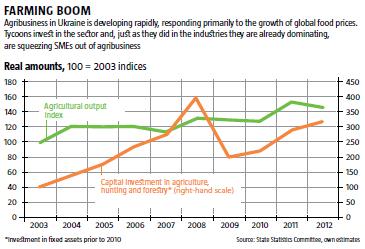

With its vast areas of fertile soils, Ukraine seems destined for agricultural success. However, there was minimal development in farming until about 2005. There was no land regulation while grain prices did not make the business profitable. Foreigners who had all the latest technologies did not rush to invest in Ukrainian, since their access to land was restricted, plus they faced an unfavourable investment climate. In 2004, investment in agribusiness was a meager UAH 3.4bn per year.

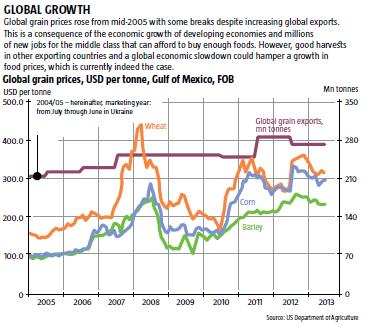

This changed in 2005, largely thanks to certain liberalization after the new government came to power. Foreigners started investing in Ukrainian agribusiness, bringing in new technologies that also spread among Ukrainian farmers. From June 2005, global grain prices rose steadily. This lasted almost until the onset of the crisis. Even the good worldwide harvest in 2007-2008 that boosted global exports by 10% and knocked down prices did not inhibit the rise (see Global growth). All this facilitated investment in Ukraine’s agriculture and gradually boosted output from 1.82 tonnes per hectare in 2003 to 3.46 tonnes per hectare in 2008 (see Farming boom).

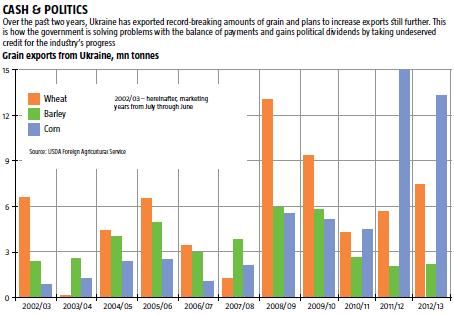

Today, investment rate in agriculture remains among the highest in Ukraine while the industry has found itself in a very favourable environment. Banks are more eager to lend to agribusiness, which enjoys significant tax privileges. Over the past year, large and medium-sized businesses involved in agriculture earned UAH 27bn in net profit, i.e. 68% of the net profit of all Ukrainian enterprises, but paid less than 1% of total income tax. In addition, grain traders owned by people close to the government, gained extensive opportunities to export grain after yet another redistribution of the grain market: almost 23mn tonnes of grain were exported in the 2012/2013 marketing year (see Cash and politics). They have received sustainable revenues in foreign currency, as well as the possibility to obtain easy and cheap funding from abroad.

Growing crops has become lucrative enough to attract oligarchs who are used to extensive business development through dirt-cheap privatization and the distribution of the state budget. As a result, the farming tycoons who at that time included Oleh Bahmatiuk with UkrLandFarming and Avangardco, Andriy Verevskyi with Kernel Group and Yuriy Kosiuk with Myronivskyi Khliboprodukt, were joined by first-wave oligarchs, who only recently turned to agribusiness, including Rinat Akhmetov, Vadym Novynskyi, Ihor Kolomoiskyi and Serhiy Taruta.

Ukraine is expecting a record-breaking crop of cereals this year that may well exceed the 56.7mn tonnes harvested in 2011. Cereal exports could subsequently rise significantly. According to the US Department of Agriculture’s forecasts, Ukraine could become the second biggest grain exporter after the US in the 2013/2014 marketing year if it sells 30.2mn tonnes abroad.

In an effort to gain its own dividends, including political, on agribusiness development, the government is taking credit for the boom. But this is wishful thinking since farming began to develop intensely way before the current government came to power, while the tax privileges it initiated will hardly facilitate the agricultural sector development effectively, given last year’s high profits. Instead, they will add to the burden on taxpayers.

Another reason for the government’s close attention to agribusiness is the balance-of-payments issue. In 2012, Food Stuffs exports where grain accounts for 39% made up 26% of Ukraine’s total exports of goods, almost catching up with long-time leaders, iron and steel. Based on data for the first five months of this year, metallurgy and machinery product exporters will earn nearly USD 3.5bn less from exports in 2013 compared to previous year. The government hopes to offset this loss in trade balance with revenues from exported grain. However, the grain price would have to increase 1.5 times to cover the loss, but world prices are currently falling. On August 14, September futures for corn fell by a further 14% below the rate as of June 31, and are 17% below spot prices. Wheat futures fell 4%, and are 19% below spot prices (see Global growth).

READ ALSO: Investing in Ukraine’s Future: Removing Barriers to Open Opportunities

Meanwhile, government officials keep talking about the potential of agribusiness, as if expecting it to become a reality this year. The potential is indeed huge: 100-120mn tonnes of grain, given average crop capacities in developed economies. This is almost twice what Ukraine harvested in its best years since gaining independence. However, based on the estimates of Oleh Bakhmatiuk, the biggest land bank user in Ukraine (according to various estimates, over 500,000 hectares), Ukraine could be able to harvest this much grain in five to seven years provided that another USD 20-25bn is invested in its agribusiness. The big question is whether this much investment can be absorbed in such a short period, when 2012 investment was under USD 2.5bn? And where would it then sell all the grain? The world is not ready to consume another 60mn tonnes of cereals which Vice Premier Serhiy Arbuzov already seems ready to export. No matter how hard the government tries to speed up the development of this sector, it will not offset the downfall of the rest of the economy or help the government patch balance-of-payments gaps.

ON THE CREST OF A WAVE

Despite the potential of farming in Ukraine, there are many bottlenecks in its development in the way that take years to eliminate. The key factor that made arable farming profitable enough to invest in its own development, even in bad years, was the world price for cereals. They grew at a rapid rate despite some slowdowns during the 2008-2010 because of the crisis. From June 2005 to June 2013, wheat, barley and corn prices grew 2.2, 2.5 and three times respectively (see Global growth). Meanwhile, global cereal export grew by 34% from 2004/2005 (73mn tonnes) to its peak in 2011/2012.

According to the IMF, real global GDP also increased by 34% over 2005-2012. So, the average growth of household income does not explain skyrocketing food prices. Moreover, to a large extent, the level of people’s income in developed economies allows them to satisfy food needs, regardless of the economic situation.

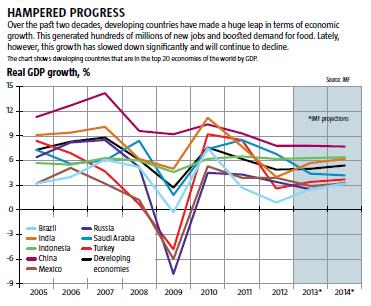

Apparently, high prices are driven by something else – significant growth in developing economies (see Hampered progress). Over the past eight years, their real GDP has grown 66%. Undeveloped Asian economies with a population of over 3.4 billion have almost doubled, growing 97%. This economic boom has created hundreds of millions of new jobs, providing an income that newly-employed consumers spent on food they could not afford before. Thus, the growth of the middle class in Asia and some African countries has become the key factor that boosted cereals prices.

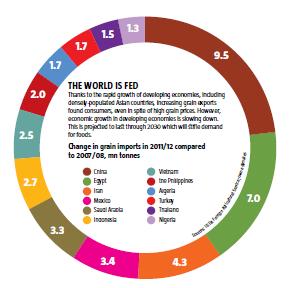

The distribution of additional exports on global markets in 2011/2012 compared to another peak year of 2007/2008 confirms this (see The world is fed). China, which has transformed from a net exporter into a big net importer of foods over the past few years, as well as smaller rapidly developing Asian economies, such as Indonesia, Vietnam, the Philippines, Thailand and Iran, consumed most of this extra grain. Much of it went to individual densely populated countries on other continents facing a high rate of economic growth and an expansion of their middle class. The twelve economies in the chart (see The world is fed) increased their cereals imports by almost 41mn tonnes while global exports only grew by 33mn tonnes. Their high solvency coupled with high grain prices have even allowed them to squeeze out some cereals importers that had previously shaped the market.

This has brought Ukrainian agribusiness to the crest of the global wave of middle class growth in developing countries. But this wave has ebbed (see Hampered progress) and the future no longer looks so clear or bright for Ukrainian farmers.

Firstly, even if Ukraine does realize its agricultural potential and produces 100-120mn tonnes of grain a year, it will have to export 60-90mn tonnes (such volumes cannot be consumed by the domestic market), which exceeds 2012 and 2011 peak amounts by 35-65mn tonnes. Will the third world generate at least 2/3 of the demand it added to the marker over the last decade to absorb this skyrocketing output, provided that other players on the market do not increase their grain exports? This is unlikely since, according to various estimates, developing economies will not grow at the present rate in the next 10-15 years. So, they are unlikely to create many new jobs to boost global demand for foods in the foreseeable future.

Secondly, grain prices are showing a curious trend. They plunged very low in 2009 and 2012 when growth rate of Asian economies slowed down to below 7% per year. Huge harvest and a 15% increase in the global export of cereals in the 2011/2012 marketing year against a backdrop of the economic slowdown in Asia led to a further 20-25% fall in wheat and corn prices. So producing and exporting more crops does not necessarily mean higher revenues.

If Ukraine does realize its grain potential, global grain exports will rise by 15-20%, and global competition will increase. In that case, the “driver” of Ukraine’s economy may transform into a burden while the government’s proud “Let’s feed the world together!” may become a cry of despair. Some economists justly warn those in power against the overstated expectations of Ukraine’s agribusiness in 2013 and note that they should prepare for the opposite. Transition economies are slowing down and the whole world is expecting good harvests this year, so Ukrainian farmers could face tough competition on the global market, while revenues from the sale of cereals may be way below last year’s. The current dynamics of grain prices confirm this concern.

READ ALSO: Colossi With Feet of Clay

No matter how the 2013 harvest turns out though, Ukraine should probably search for strategic buyers and sign long-term contracts for its supply. If not, global competition may well kill the effect of much of the investment in agribusiness.

THE OTHER SIDE OF THE COIN

Regardless of how profitable Ukrainian agriculture will be in the future, one thing is clear: it will develop for at least the next five years. Even if global competition eats up one third or half of current cereals prices, crop farming will remain profitable in Ukraine although investment may shrink. Even though the current situation carries significant risk, given the extensive nature of commercial farming. Big business, which is currently investing heavily in agriculture, is counting on quick profits, so it focuses on growing plants that exhaust the soil, especially industrial crops. Over 2005-2013, sunflower fields grew from 3.7 to 5.2mn hectares; corn fields went from 1.7 to 4.7mn hectares, while land used for growing rapeseed increased from 240,000 to almost 2mn hectares.Meanwhile, the acreage of traditional food crops is dropping. If this practice continues, it will cause the fertility of Ukraine’s black soil to decline and the current farming tycoons will actually leave behind scorched earth.

Agribusiness development can also bring dramatic change to rural Ukraine, home to over 14 million people or 31% of the total population. Modern technologies ensure high productivity so farmers will need fewer people to work in the fields. In the US, less than 1% of the population or 2 million of employed Americans, work on all of the country’s farmland. This is where Ukraine could be heading. The rest of Ukraine’s rural population will then face one of few possible scenarios.

READ ALSO: A Road Map for Economic De-Sovietization

Whenever something like this happens, villagers gradually migrate to towns for work and a better life. All developed economies went through this as their farming evolved. In Ukraine, this will require the creation of as many jobs in other industries as the number of people that will lose their jobs as a result of the commercialization of farming. Currently, however, Ukraine’s industry and services sphere are in steep decline, nor will they develop anytime soon, given the current situation in Ukraine and the government’s economic policy. So there are no prospects for Ukrainian villagers in cities. Another option is migration to developed economies and a further decline of Ukraine’s population. If the government abolishes the ban on the sale of agricultural land, migration could well accelerate in the long run, because other than a house and an adjacent patch of land – which is not worth much – there is nothing to keep people in villages. They will have no work and will sell whatever land they currently own. Therefore, without a comprehensive economic strategy, the development of agriculture may trigger many socio-economic challenges.

In his book How Rich Countries Got Rich… And Why Poor Countries Stay Poor, Norwegian economist Erik Reinhert argues that agriculture never made any state rich. On the contrary, its development always cemented a country’s backwardness. Producers of agricultural foods, just like those of other commodities, rely heavily on a strong manufacturing and its growth. If the latter suffers a crisis, farmers fall hostage to low prices, income and sluggish growth. It appears that the Ukrainian government views agriculture as nothing but a tool to solve its current problems, declaring it to be the “driver” of the economy. Oligarchs apparently view it as a way to make a quick buck.