Ukraine is increasingly reaping the fruits of the import dependency into which it has systematically moved over the past few decades. The steep revaluation of hryvnia via accumulation of debt since the latest transfer of power has sharply aggravated problems accumulated over the years of misguided economic policies.

Ukrainians spent UAH 1.5 trillionon imported goods in 2018. According to official data alone, Ukraine imported US $57.2 billion in goods in 2018 and is forecast to import US $61bn in 2019. It’s no secret that a great share of imports comes through semi-legal schemes, where declared customs value (DCV) is much lower than the real value, or through outright smuggling. Data from Derzhstat, the government statistics service, also points to a trend for the net share of imports to increase in the balance of trade, year-on-year. In 2005, Ukraine imported 29.5% of all goods sold on its territory, including 42.4% of foodstuff. In 2018, that share was at 58%, including 64.7% of foodstuffs.

Meanwhile, critical imports are on the decline. These include fuels and commodities, as well as machinery and equipment that Ukraine cannot manufacture but needs to modernize its economy. By contrast, imported food are gaining position on the domestic market, even though domestic agri-business and SMEs alike are more than capable of engaging in this type of production.

Shrinking tax collections

Thisimport-dependent economic model has put Ukraine in a position where the quantity of imports is a critical component of budget revenues. In 2019, for example, different import fees were expected to generate UAH 415.3bn of the UAH 860.7bn of total budget revenues expected from taxes. The negative impact of this dependency is becoming more and more of a burden for Ukraine.

RELATED ARTICLE: Between a rock and a hard place

Meanwhile, the steep revaluation of hryvnia has made it more difficult to fill the state budget. According to the Treasury, Customs failed to meet its revenue plan for Q3’2019 and fell 10.2% behind collections in the same period of 2018. This trend has been getting worse every month. In July 2019, Customs was UAH 0.9bn short of planned collections, and 0.5% below revenues for July 2018. In September 2019, the shortage was UAH 4.9bn or 12.6% below the September 2018 figure.Q4 2019 is looking even worse. In October 2019, the shortfall was UAH 5.8bn, or 14.7% down from 2018. By November 18, revenues were already 19.3% below last year.

The tax administration has been performing equally poorly. Domestic taxes collected in July 2019 outperformed planned revenues by 23.4%, while July 2018 outperformed by 43.5%. In August 2019, however, collections were 6.1% short of planned and only 11% higher than August 2018. In October 2019, the shortage was 8% and this was 5% below the October 2018 figure – less even than inflation for this period.

Shrinking tax revenues are the result of an import-oriented economic model: industrial decline has been growing as domestic producers lose their competitive edge, both at home and abroad. While the processing output inched up 1.1% over January-May 2019, it has been in the red since June, declining 4-6% month-on-month in some months. Moreover, the industries that drove GDP growth to a record-breaking 4.6% in Q2’2019 were the same ones that pay little in the way of taxes for a variety of reasons: trade was up +4.5%, agriculture +7.3%, other services +14.5%, and construction +20.5%. Moreover, thanks to temporarily favorable factors, commodity exports grew, further aggravating budget shortfalls as they mean higher VAT reimbursements to exporters.

Growing debts

Ukraine compensates for this massive shortfall in budget revenues by borrowing, mostly by placing hryvnia-denominated bonds on the domestic market. According to the Ministry of Finance’s report on the 2019 budget, domestic borrowings tripled in Q3, rising UAH 67.6bn, from UAH 32bn to UAH 100.4bn. Foreign borrowings decreased UAH 17.9bn, from UAH 22.4bn to UAH 4.5bn. All payments to service the public debt were only UAH 29.5bn higher than in 2018. This means that UAH 27.6bn of borrowed money was used to cover current budget spending, compared to only UAH 6.6bn in Q3’18.

From May through September 2019, Ukraine sold over UAH 60bn-worth of government bonds, while hryvnia went from UAH 26.80 to UAH 24.10 to the US dollar. In October, the amount invested by foreigners in Ukraine’s government bonds was over UAH 100bn, and it keeps growing. Foreign investors are mostly buying mid-term bonds due in two-four years. Their high yields of 13-15% over this period can offset even a serious devaluation of hryvnia, which makes such speculative investment beneficial in an environment where most developed countries offer zero to negative interest rates. As they buy bonds, foreigners bring in currency to Ukraine and sell it in the country, which artificially strengthens the hryvnia. The net result is that revenues from Customs decline, while actual import rates rise.

On November 5, MinFin sold UAH 3.14bn in government bonds. Four-year bonds with a weighted average yield of 13.3% accounted for UAH 2.31bn, the lion’s share of the total. On November 12, MinFin sold three-year UAH-denominated bonds worth UAH 2.64bn, with an weighted average yield of 13.1%, and dollar-denominated bonds worth US $304.9mn. At UAH 264mn and UAH 524mn, six- and 11-month bonds barely sold despite 13.7%-14.1% yields and smaller installments. On November 19, just bonds worth just UAH 1.32bn were sold, including barely 10% in three-month bonds, and almost half, worth UAH 664mn, due in 22 months, on September 30, 2021. Their weighted average annual yield is 13.5%.

Despite the cheery headlines about another successful bond placement, in reality, every time MinFin sells government bonds, it pushes the hryvnia up or down, to the day. When bonds sales are high, the hryvnia gets stronger; when the sales are weaker, it sinks a bit.

A suicidal path

A stronger hryvnia makes imported goods more attractive and leads to their growth at the same time as it chokes competition among Ukrainian goods both internationally – other than for commodities – and domestically: imports from the world’s megafactories in China and other Asian countries squeeze out “made in Ukraine” goods. As a result, Ukrainian exports have been stagnating and even declining in all categories except ores, grains, oilseeds and oils. At the same time, revenues from such commodity goods are neither sustainable, nor reliable.

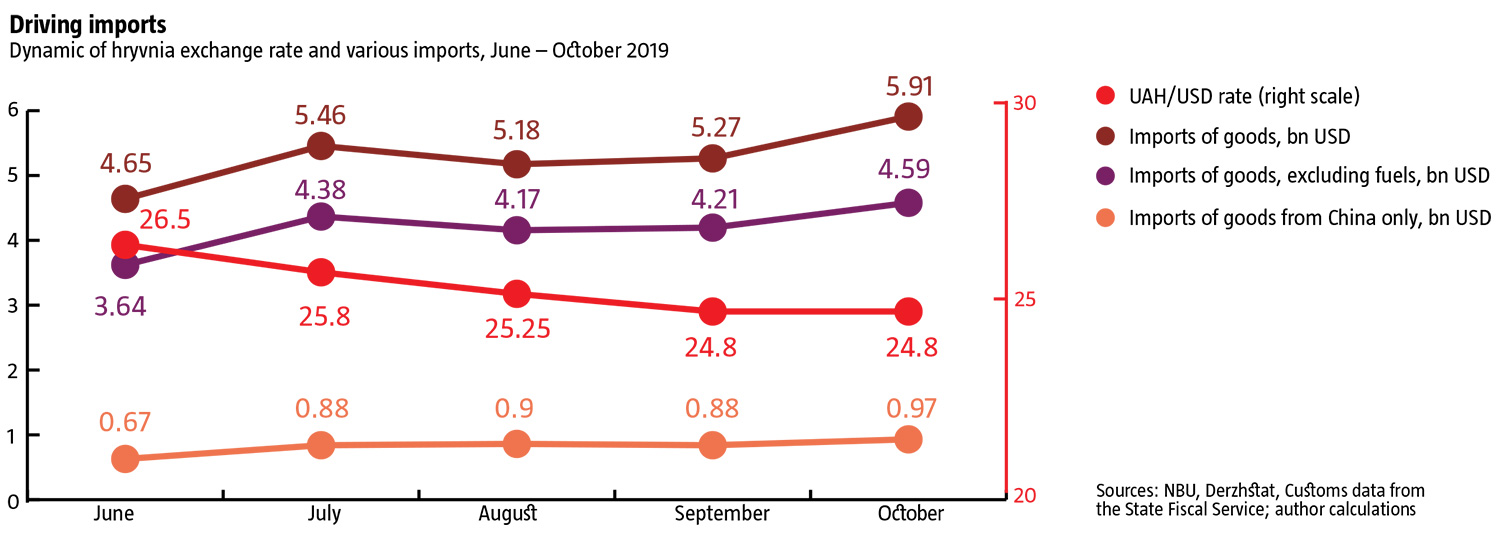

Ukraine imported a total of US $28.2bn in goods in the first six months of 2019, an average of US $4.7bn per month. In July, imports grew to US $5.46bn, and in October they were US $5.91bn. This growth is mostly driven by consumer goods, not fuels, one of the critical imports. For example, Ukraine imported US $22.47bn-worth of fuels over January-July 2019, an average US $3.74bn monthly, including US $3.64bn in June. This figure rose to US $4.38bn in July and US $4.59bn in October.

Meanwhile, imports of consumer goods from China are growing the fastest, for a total of US $3.92bn in the first six months of 2019 – an average of US $653mn per month. Chinese imports were US $665 in June, US $880mn in July, US $903mn in August and US $965mn in October.

Consumer imports to Ukraine are de factodriven by the state bond debt pyramid that Government is growing as a panacea, while budget revenues are in decline as a result of plummeting Customs and tax revenues. The debt pyramid is making imports cheaper in hryvnia, aggravating the problem of budget fulfillment and driving further borrowings. This further strengthens the hryvnia and reduces budget revenues.

This vicious cycle is damaging both Ukraine’s current budget revenues and its long-term economic prospects. The strengthening hryvnia pushes revenues further down, forcing the government to tighten public spending. As The Ukrainian Week reported previously, social spending is the first item to be cut. Yet, relatively low-income vulnerable groups and public sector employees actually tend to buy few imported goods. These are the two groups that mostly spend on domestically-made goods and services. As their incomes go down, driven by cuts in public spending, it stifles domestic demand for goods and services made in Ukraine.

Other public expenditures that could fuel demand for domestic goods and services are curbed too. Instead, the focus remains on purchasing foreign equipment: Interior Minister Arsen Avakov recently decided to buy patrol boats worth several hundred million euros from France after buying French helicopters last year – because, unlike many western countries, there is no “buy Ukrainian” requirement in public procurements.

My kingdom for a horse?

The new administration’s bet on a land market to fix the trade deficit caused by this suicidal policy will actually make things worse. The money that will come to Ukraine from foreign buyers will further strengthen the hryvnia for a time, fueling more imports of consumer goods. The planned revision of criteria for subsidy eligibility will leave many landowners with a serious shortage of money, pushing them to sell land faster, pushing property prices go down and bringing more foreign currency into Ukraine. This will continue propping up the hryvnia and undermining tax revenues from imports, even if in dollar terms they grow.

RELATED ARTICLE: A little less conversation, a little more reforms

In the end, the easy money Ukraine will borrow via hryvnia-denominated government bonds or sales of farmland risks being absorbed by imported consumer goods whose producers are looking for new markets as trade wars intensify across the world. What Ukrainians will end up with is new debts and the loss of a good portion of their national assets, farmland, some privatized enterprises and, most importantly, an undermined non-commodity economy. This will be hit by the sharp decline in domestic competitiveness as imports get cheaper and of Ukraine’s position on global market as the hryvnia revalues.

Ukraine still has time to replace its import- and debt-dependent development model – really a financial and economic model for self-immolation – with a model focused on developing national manufacturing to drive import substitution and exports.

Translated by Lidia Wolanskyj

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook