In 2016, Ukraine’s economy grew 2.4%, rising to 2.5% in 2017. This past year, President Poroshenko says it grew 3.4% and the Government has projected 3.0% growth in 2019. The NBU is less optimistic, forecasting 2.5% growth in 2019. A popular folk saying is that stability is a sign of excellence. But public reaction to this kind of stability is mixed. On one hand, Ukraine’s entire government proudly reported in unison that the country’s GDP was picking up pace as one of its achievements. On the other, the premier keeps saying that this is too little that Ukraine’s economy needs to grown 7-8% annually in order to not just recover but to move up. Finally, those who feed on bad news see the actual pace of growth as the final collapse of the Revolution of Dignity and of all those whom it brought to power.

This kind of situation makes it hard for ordinary people to understand who’s right and what these rates of growth actually signify, so The Ukrainian Week has tried to figure it out.

If GDP growth is looked at in the abstract, 3% growth is a middling rate globally. According to the IMF’s October assessment and forecasts, the world economy grew faster in 2017 and 2018, at 3.7%, and should grow the same in 2019. Given that wealthier economies generally grow more slowly, the average pace of growth of developing economies is about 50% higher, or 4.7% according to the IMF. This means that Ukraine is not only not catching up to its wealthier neighbors, such as Poland and Turkey, but falling behind more and more. If this fact is removed from its circumstances, the situation comes across as even less cheering. But an in-depth look at the components presents a more ambiguous picture.

Exports as litmus paper

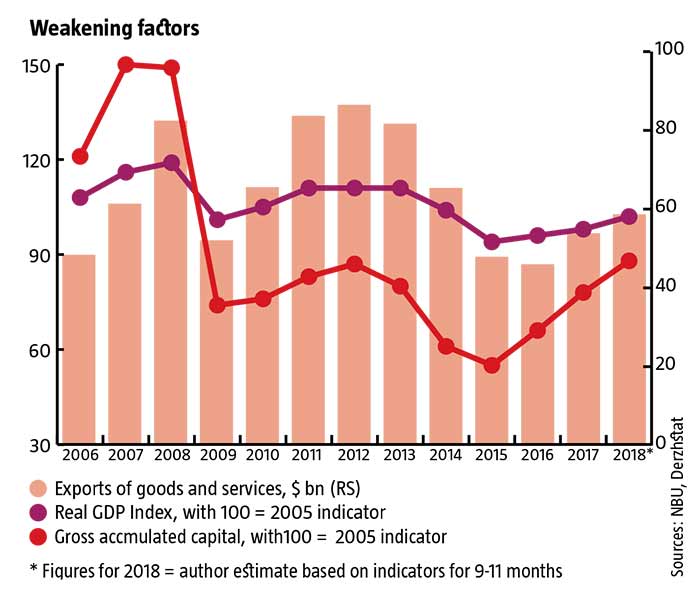

Take exports. They constitute more than half of GDP, so they are a key factor in economic growth. Over 2014-2016, exports went down nearly 50% (see Weakening factors), mainly because of the ruination caused by the war in the Donbas, which caused Ukraine to irreversibly use considerable economic capacity and a lion’s share of its export potential. All this is clear from economic indicators. During the 2008-2009 financial crisis, there was a similar collapse in exports, but things picked up again within three years, when GDP was growing 4-5% a year. This time, there is no way to recover to previous levels again. Yes, the export of goods keeps growing, but this growth is coming from completely different companies and sectors than prior to the crisis: three years after the crisis ended, indicators are still only 67% of their pre-crisis peak.

Another important factor is at play here, too. In theory, export is one of the economic powerhouses that has the strength to self-regulate. If the volume of goods being shipped out goes down for whatever reason, a trade deficit appears. This, in turn, drives the national currency down, making prices for domestic goods and services that were not previously being exported, more attractive on foreign markets. This leads to export growth and compensates a good part of start-up costs. In short, a decline in exports eventually ensures its rise in another area. A similar kind of self-regulation should take place whenever there are large-scale losses at an individual enterprise: demand for its goods did not go anywhere and the ensuing shortage causes prices to slowly rise again, making investment in restoring ruined manufacturing facilities and one-time production output levels. In Ukraine, however, there was no sharp increase in export volumes or significant capitalization in restoring the ruined enterprises in the Donbas, or their transfer to non-occupied territory. What does this suggest?

RELATED ARTICLE: Slaloming the risks

First of all, it reflects a lack of business acumen. The hryvnia went down to less than a third of its previous value. Foreign tourists find the country unbelievably inexpensive. Even the Big Mac Index produced by The Economist indicates that the hryvnia should be three times higher and the dollar should cost only about UAH 9.80 in Ukraine. This means that after exports declined during the 2014-2016 crisis, enormous export potential appeared again – and this needs to be taken advantage of. Ukrainians should be making just about anything or buying it domestically and selling it in Poland and elsewhere. If Ukraine had enough savvy entrepreneurial types, half the country would be busy doing precisely this. Exports would be on the rise like yeast and the dynamic of the GDP would be far more lively than the current 3%.

For some reason, this isn’t happening. We could try blaming it on Ukraine’s loss of the Russian market, or Ukraine needing time to adjust to the demands of the EU market. Except that the hryvnia is extremely cheap for four years and a bit, which means also the cost of manufacturing located in Ukraine. In other words, there’s been more than enough time to adjust to the new conditions and the economy has been responding, but far too little. If Ukraine had enough entrepreneurial folks, manufacturing and exports would be growing a lot faster. Instead, their growth is weak and Ukrainians themselves are choosing to emigrate rather than to try manufacturing something on their own at home.

Breakthroughs and obstacles

Secondly, the reality is that there is no technological capacity or economic sense to trying to restore the majority of the industry destroyed in the Donbas. Those facilities were anyway inherited from soviet times. The oligarchs managed to squeeze some juice out of them somehow, paying people very little and driving them like animals in a herd, but building a piping or steel plant from the ground up is more than any of them are capable of. Indeed, the number of technological breakthroughs since Ukraine became independent can be counted on the fingers of one hand and the people responsible for them are treated almost like gods in Ukrainian business circles. That’s the whole point: in order for the country’s economy to grow, Ukrainians have to build it – and that means knowing how to do that – but not all of Ukraine’s billionaires are capable of this.

The feasibility of restoring what was ruined is also extremely doubtful. Most of the facilities belonged to the third, and partly the fourth technological generation. The goods that they produced have many equivalents around the world and their markets are extremely competitive. Their disappearance from the global economic map has gone unnoticed. When the level of breakdowns with which these factories operated is factored in, investing in them is clearly a waste of money.

Thirdly, conditions for doing business in Ukraine also need to be kept in mind. In general, they probably got better during the Yanukovych Administration, but most of the economic capacities lost in the Donbas belonged to oligarchs who always enjoyed special conditions that they agreed with whoever was in power. Meanwhile, the exports that are just emerging today are generally being produced by SMEs that are not protected against the abuse of enforcement, tax or customs officials. That makes it very hard for them to enjoy the kind of success that oligarchic businesses had under hothouse conditions. And so, although exports are far more diversified today than they used to be, they are growing more slowly as well. The main conclusion that can be drawn is that if obstacles to doing business were removed for SMEs, manufacturing and export both would grow much more noticeably. But those in power need to understand that, so far, governments have been more inclined to create obstacles to commercial activity than to help business grow.

Investing in manufacturing

Investment is the other key factor to economic growth. Here, a number of interesting facts emerge. For instance, in the last three years, the gross fixed capital formation or net investment has grown nearly 60% (see Weakening factors). Moreover, this indicator was higher in 2018 than in 2012, the best year between the previous two financial crises. Apparently, investors weren’t investing then because they were aware of all the risks connected to the Yanukovych regime. Now, they are investing capital, despite the war, which testifies to some key improvements. The level of investment is still too small to spur economic growth, but it already offers hope that the situation in Ukraine will change for the better.

Over the last four years, 207 new factories opened their doors in Ukraine. Most of them are ventures by foreign investors. So far, the facilities are not large, hiring several hundred workers and altogether creating a few dozen thousand new jobs. This is less than 1% of the labor market in Ukraine, so their contribution to GDP growth is not very big for now. What’s important about this today is that the country is already being seen as potentially a full-fledged component of the European market, which is why the owners are trying to get in while wages are still low and the manufacturing facilities here can pay for themselves within a few years. The minute this trend becomes large-scale, the domestic economy is guaranteed to start growing at a good clip. The main thing is for this to be a qualitative growth in real jobs. The more foreign manufacturers build facilities in Ukraine, the more developed countries in Europe and elsewhere will have a stake in Ukraine’s security. This kind of partnership is win-win for all involved.

Shifting demand

Another key factor, one that few people talk about, is the change in aggregate demand as structural reforms progress. Schematically, it can be described thus: as reforms take place, demand grows for new goods and services in considerably larger volumes that the economy did not experience earlier. Supplies need time to adapt to new structural demand, to get the technology and labor necessary, to win tenders, sign contracts and establish market infrastructure. And demand needs time to find the right supply. This means that there can sometimes be a temporary manufacturing vacuum, where the buyer wants to buy something and has the financial resources, but the seller can’t sell enough of it. This can make it seem like the economy is slipping, but in fact it’s getting the resources together that are necessary for the next leap. And as soon as manufacturing adapts to the new conditions, the given market for goods and services begins to grow strongly,

There are several good examples of this, such as road construction. In 2013, UAH 15.5bn was allocated and 625 km of roadways were restored and resurfaced. In 2019, more than UAH 49.0bn will be spend just from the public purse, plus money from international donors for individual projects – and more than 4,000 km of roadways are slated to be redone. The point is not just that the budget for road building has tripled and the amount of roadway sextupled, but that this scale of roadworks requires that the process itself be properly organized and the manufacturing capacities prepared: ProZorro has been established and launched, all tenders are now going through the system, and both buyers and contractors are using this new platform. Meanwhile, equipment has been purchased, people hired, foreign builders invited to get involved and bring their own equipment, and so on. Once this system is running smoothly, it will be possible to redo even 10,000 km of roadway a year. Moreover, the impact on GDP growth will be proportionally affected as well.

RELATED ARTICLE: Twilight of the oligarchs

The same is true of decentralization. Just a few years ago, how many local government agencies had the skills and experience necessary to prepare business plans and grant proposals to get financing to, say, change all the windows in a school or to buy school buses? Even fewer probably had the budget to do so. Now the money is available but experience is lacking. And so local governments have huge surpluses of unused budget funds that lying around doing nothing in bank accounts. Over 2018, this surplus was often more than UAH 15bn. By the end of November, it was UAH 12.6bn. Obviously, if this money were working, they could be turned over several times over the course of a year and have a considerable impact on GDP growth. But this did not happen for objective reasons.

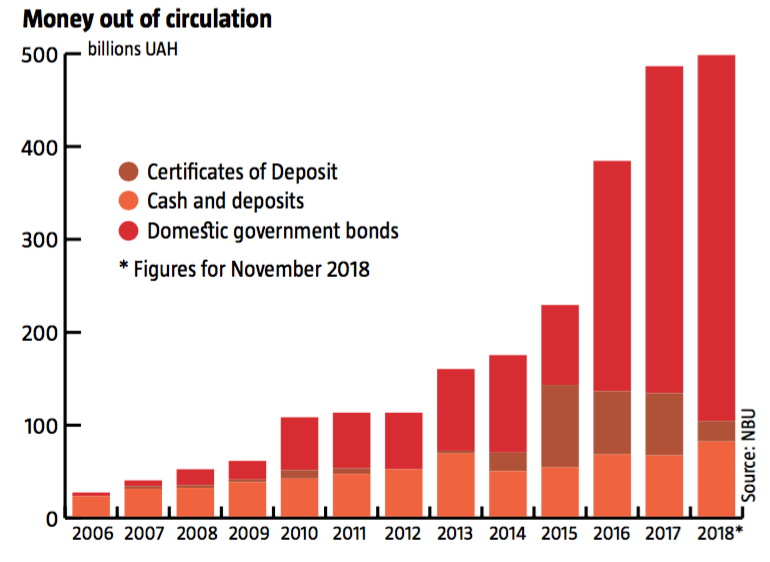

A similar situation was taking place in the banking sector. As a result of widespread reforms, domestic banks became highly liquid (see Money out of circulation). But the selection of borrowers became very limited because financial institutions were forced to stop lending to related parties and engaging in other risky practices, while finding a suitable number of creditworthy borrowers on the market proved easier said than done. The result was that, over the last four years, banks have held considerable liquidity in NBU certificates of deposit and even more in government bonds. In the former case, the money wasn’t working at all because it had been taken out of circulation. In the later case it went largely to consumption and even to pay for populist government whims. It will take time for everyone to adapt to the new requirements of banking institutions and their borrowers. But lending is already picking up pace again, which is very necessary to keep investment dynamics up. Still, a few years were lost and that is what we see in the GDP growth dynamic being reported.

The good news-bad news of migration

Last, but not least, is migrating labor. The country’s economy cannot grow quickly if it’s losing labor rapidly, especially highly qualified specialists. It’s not just that more workers mean higher volumes of output. A labor shortage pushes wages up. This is good for the workers themselves, and it stimulates business owners to increase productivity and to invest in growing their business – which, in and of itself, can have a positive impact on economic growth.

But there is a definite limit beyond which high wages will begin to have a harmful impact on business. As it becomes less profitable to produce goods and services, companies begin to cut back production or shut down altogether. At that point, GDP is likely to go into decline. And so labor migration needs to be kept at a minimum before things get to this point.

In short, what we have is a situation that is not straightforward. On one hand, there are factors that are holding back economic growth and their effect is disheartening. On the other, there are positive trends that give cause for hope. And then there are those factors that have no impact either way on GDP growth but they can shore it up over time. So, 3% GDP growth is the reality Ukraine faces today. In this situation, the country cannot afford another deep economic crisis under any circumstances, to lose in a year what it has achieved through gargantuan effort. If it manages to avoid this, the economic bottlenecks that are getting in the way of 7-8% growth will eventually be worked out.

Translated by Lidia Wolanskyj

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook