Whether people want them to be or not, their impressions of regions even within their own countries are often shaped by myths—and Crimea is no exception. Most Ukrainians tended to think of the peninsula—with the exception of Sevastopol—as a beach resort and wine-making region, even during soviet times. In fact, it was not quite like that under the soviets. The myth about the “all-union health cure resort” was originally started as propaganda to cover the truth the real nature of the economy of Crimea. Based on how its residents were employed, how its territory was utilized, what the state invested in it, and the volume of manufacturing produced on the peninsula from after WWII until the USSR collapsed, it was:

– firstly, a huge army, navy and air base—and eventually a nuclear and space base—that all ensured the Soviet Union’s dominion in the Black Sea region and its access to the Mediterranean and in the Middle East;

– secondly, a major industrial R&D center in the Union for making military instrumentation and shipbuilding;

– thirdly, one of the food-processing centers of the USSR specializing in processing fish caught in the oceans—most of the commercial ocean-going fleet of the Ukrainian SSR was based in Sevastopol and Kerch—as well as vegetables, fruit, grapes and wine.

Crimean industry was based on dozens of enterprises making military instruments, building ships and repairing sea-going vessels. That’s where ships for the Soviet Navy, guided torpedoes, missile control systems, navigational and radio equipment, tank sights, complicated parachute systems, including for space rockets and for landing tanks, and so on.

Prior to the 1990s, foreign tourists were forbidden to leave Simferopol to go anywhere except Yalta and Alushta. Sevastopol was off limits even to those who lived in Crimea unless they had a special permit, while even residents of Sevastopol could only enter Balaclava, where the Black Sea Fleet was based, with special permits. Soviet resorts were not a flourishing sector of the economy but, on the contrary, a costly state-funded social program of the Soviet Union.

Post-soviet demilitarization

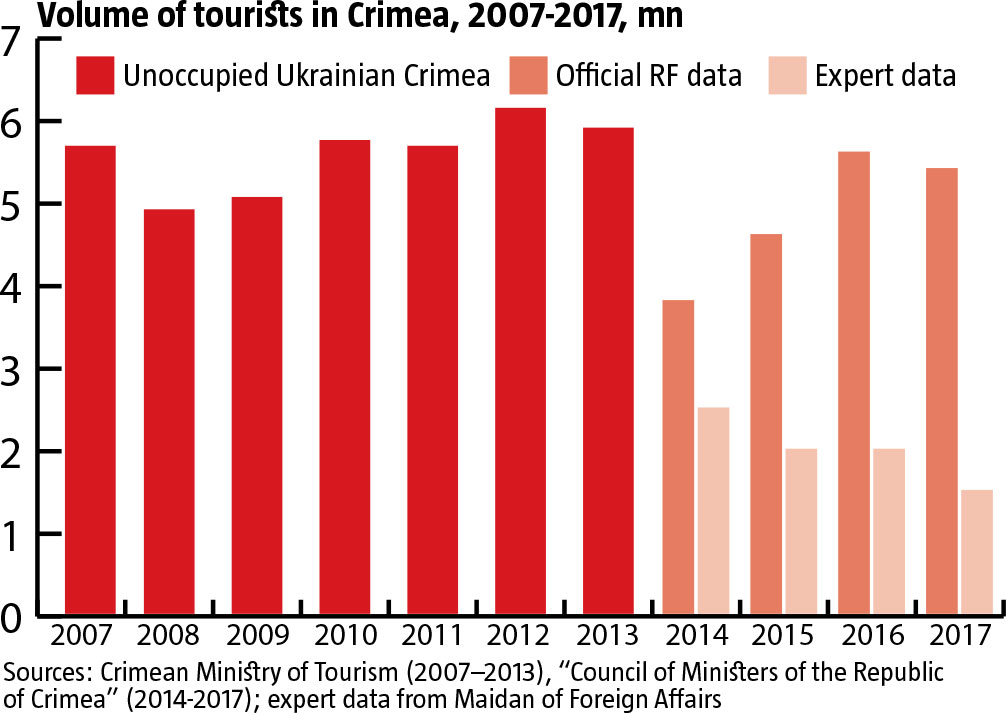

With the end of the Cold War, during the perestroikaperiod and after the USSR collapsed, the military specializations of the Crimean economy were completely lost. But defense itself was not the only victim: light industry disappeared almost completely during the 1990s. With the exception of grains, sunflower, vineyards and poultry, farming reverted to small household holdings. The resource base for producing fruits and vegetables was lost Crimean orchards shrank by more than 80%. Under market conditions, Crimean dairy production pretty much disappeared, as did canned fruit and vegetable and juices. The number of tourists shrank collapsed from 7.9-8.3 million in the mid-1980s to only 2.3mn in the mid-1990s. The jobless workforce was slowly taken up by small enterprises that were not a product of the middle class but simply a means for the local population to survive.

Slowly Crimea’s economy took on a new shape and by 2001, going through 2010, the main driver was the chemical industry based on the North Crimean chemical complex where titanium dioxide and sodium carbonate were produced, and the extraction of oil and natural gas on the marine shelf. After the start of the land boom in the mid 2000s, housing also became a major business. The relative weight of farming continued to shrink as trade and services grew stronger.

RELATED ARTICLE: The island of bureaucrats and soldiers

Following the 1998 financial crisis, Crimea’s economy picked up pace again over 2001-2008, but tourism, at only 7-8% of the peninsula’s economy, trailed behind industry, trade, transport, farming and construction. But this is when resorts and tourism, initially through growing awareness among Ukrainians and officially starting in 2010, became a strategic priority for the Crimean economy. Over 2011-2013, tourism grew visibly, as did the services related to it. As small enterprises quickly grew in this business, major investment projects began to come to the peninsula. At this point, some 6 million tourists were visiting Crimea every year and by the end of 2013, tourism and recreation were generating at least 25% of the autonomous republic’s consolidated budget. Three main regions where resorts formed a mono-economy served more than 75% of all visitors—Yalta with 38%, Alushta with 19% and Yevpatoria with 19%—and brought in over 20% of consolidated budget revenues between them.

A major indicator of the success of this shift was the fact that Crimea had become the main center for international tourism in the Black Sea: in 2013, the peninsula’s ports had received 187 foreign cruise liners, adding up to nearly 105,000 passengers. These were record numbers, not just for independent Ukraine but also for all of Crimean history. By 2014, growth was up to 70-80% (before the takover). By 2010-2013, grain-growing was almost at soviet levels, with more than a million tonnes per year, as was wine-making. Indeed, the production of cognacs was 5-6 times more than it had been in the 1980s.

In short, at the point when Russia invaded, Crimea’s economy was demilitarized and a completely new focus on tourism and services had become its strategic priority.

“A new showcase for Russia” — FAIL

Although the main purpose for occupying the peninsula was military and strategic, the idea of Crimea as a “new showcase for Russia” gained enormous popularity in 2014, similar to the Olympics in Sochi, but based on tourism and innovation rather than sports, complete with its own Silicon Valley, gambling resorts, free economic zone, cutting-edge technologies, 7-star hotels, just like the Emirates. There was a brief euphoric boom of ideas for developing the peninsula and visitors galore from major Russian businesses. Indeed, two weeks after the annexation, on March 31, 2014, the Russian Federation even established a new Ministry of Crimean Affairs.

But by the beginning of 2015, Moscow understood how impossible its initially ambitious plans for economic development on the territory were and began to focus on absorbing Crimea militarily without tourism to provide a cover. On July 15, 2015, the Ministry was dissolved as well. At that point, the cumulative effect of transformations taking place began turning the peninsula into the Island of Crimea and a grey zone because of a transportation and later energy blockade by mainland Ukraine, and international sanctions. Clearly, Moscow had not expected such a response from the West and was forced to adjust its plans on the run.

In 2016, Moscow’s rejection of plans to turn Crimea into a “new showcase for Russia” was final. On July 28, 2016, it reduced the status of both Crimea and Sevastopol within the RF: Putin’s decree dissolved the Crimean Federal District, which had been formed right after the annexation on March 21, 2014. The “federal subjects” known as the Republic of Crimea and the City of Sevastopol were amalgamated into the Southern Federal District, with its capital at Rostov-on-Don. With this step, Crimea’s administrative functions were unified with the military ones, as Russia’s Armed Forces in Crimea are part of the Southern Military District with its headquarters in Rostov-on-Don as well.

Among the general population in Russia, euphoria was replaced by annoyance at the “enormous demands” of the residents of Crimea related to all the huge promises that had been made in the run-up to the “referendum.” A mere three years after the annexation, 84% of Russians thought that federal budgeting for Crimea and Sevastopol should be the same as it is for any other territorial entity in Russia. In short, even public opinion was against the notion of a “new showcase for Russia” in Crimea.

The real success story of occupied Crimea

Once it had no cover, the militarization of Crimea became obvious in 2015, not only as the main focus of the Kremlin’s Crimea policy but also the main driver of the region’s economy. The military “takeover” of this territory had now become Russia’s “biggest success story” in Crimea.

One of the signs of this “change of course” was the introduction of large-scale annual military exercises just as the peninsula’s tourist sector is preparing for visitors and right through the height of tourist season, complete with artillery fire and bombardment on the Kerch peninsula, right next to the only highway that visitors can take from Russia to the peninsula, as well as the only road bringing in supplies from the deliveries from the Kerch ferry, and from the Kerch Bridge May 2018.

Russia’s military “takeover” has led to the expansion and equipment of a gigantic military base that is larger numerically than the biggest US base in the world. In connection with this, the necessary dual-use transport, energy and other infrastructure has been established to join the peninsula to the Russian mainland: the Kerch Bridge, an underwater power link, and an underwater natural gas pipe line across the Kerch Strait.

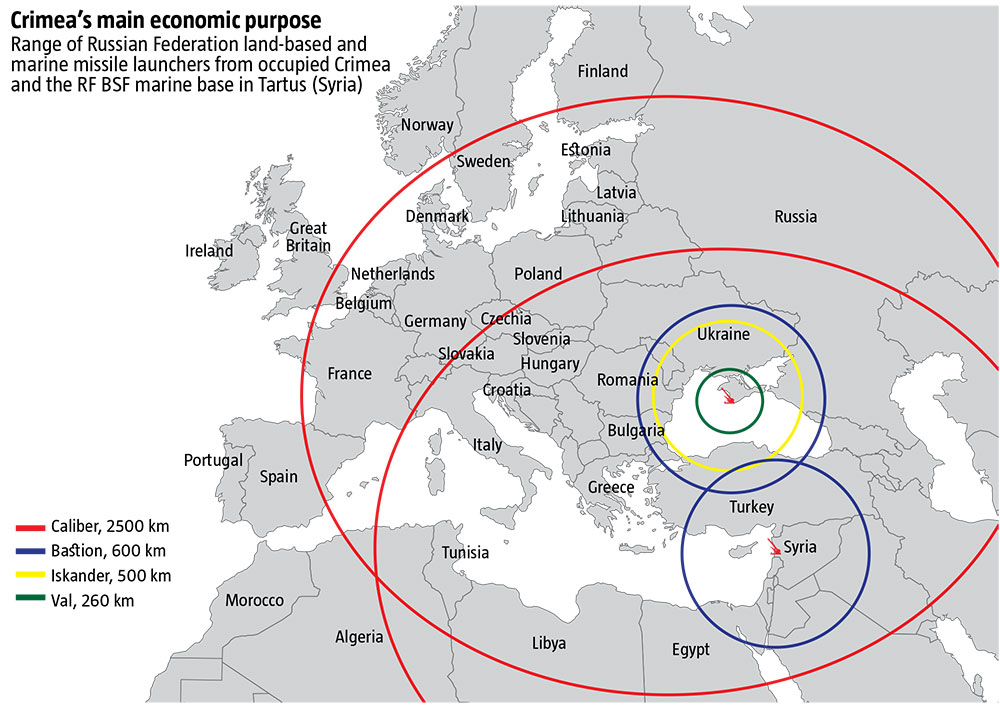

The RF Armed Forces have also been rapidly building up the biggest Joint Task Force in Europe. Crimea is now the priority location for only the latest in weapons, especially missiles. All 11 of the old soviet airfields in Crimea are rapidly being upgraded, together with missile launch sites, anti-aircraft batteries, radar systems, and nuclear weapons storage bases. A new fortification zone has been set up in northern Crimea. New military towns are being built and existing ones reconstructed for armed forces to be deployed, along with housing for service personnel. The number of different special forces has been dramatically expanded. The RF AF contingent in Crimea has been expanded to 60,000 soldiers and officers with prospects of growing to 100,000 over the next few years.

At this point, all other aspects of life in Crimea have been subordinated to the ideology of a military bridgehead: the civilian economy, the social sphere, education and the upbringing of children and teens, human rights, the information sphere, and national politics. Indeed, the development of the military base determines the priorities of the peninsula’s economy. This means, firstly, the revival of the defense industry and everything connected to military infrastructure by ensuring that Crimean enterprises get defense contracts and through state investment in infrastructure.

In 2014 alone, manufacturing in Sevastopol grew 372.9%. By the end of 2015, Crimea was declared the leader for growth of industrial output in Russia, at 12.4%. The index for industrial output in the Southern Federal District of the Russian Federation was at 106.4% in 2016, within which Sevastopol once again had the highest indicator at 121.8%. By mid-2018, the official pace of industrial output in Sevastopol remained very high at 110%.

Notably, Russian statistics on Crimea do not reflect indicators related to the Defense Ministry, the MIC or the power sector, similar to soviet times. In addition, the huge volumes of defense manufacturing, such as at the shipbuilding plants in Feodosia and Kerch that were taken over by Russia, are now included in the indicators for their new Russian “owners.”

The Pella Shipbuilding Plant of Leningrad is one of these “curators,” and then lessee of the More Shipbuilding Plant in Feodosia, which actually belongs to the state of Ukraine but was “handed over” to the federal government of Russia after the latter took over Crimea. On November 15, 2016, the More Company was officially leased out to this Russian plant until the end of 2020. Later, it became part of the Kalashnikov Concern. The More plant is building three new Karkurt-class missile corvettes in the nearby marine zone. This corvette has 8 Calibre-NK winged missiles, which are widely used by the Black Sea and Caspian Sea Fleets of the Russian Federation to attack targets in Syria, which is 2,500 kilometers away. On February 7, 2017, the plant also began production for the main border patrol hovercraft, the A25PS for the Border Service of Russia’s FSB. Plans are to produce 20 such craft.

Over the next few years, at least 9 new missile corvettes will be built at the taken over Crimean plants, with a total of 72 winged missiles of the Calibre-NK class on board. This represents a threat, not only to Ukraine, but also to EU countries and the Mediterranean region as a whole. In the second half of 2018, Russia’s BSF will begin adding vessels produced, not by Russian plants, but by plants that were seized from Ukraine. All told, defense production in Crimea and Sevastopol grew 430.8% in 2017 compared to 2015 and 227.6% compared to 2016.

Moscow’s real priorities

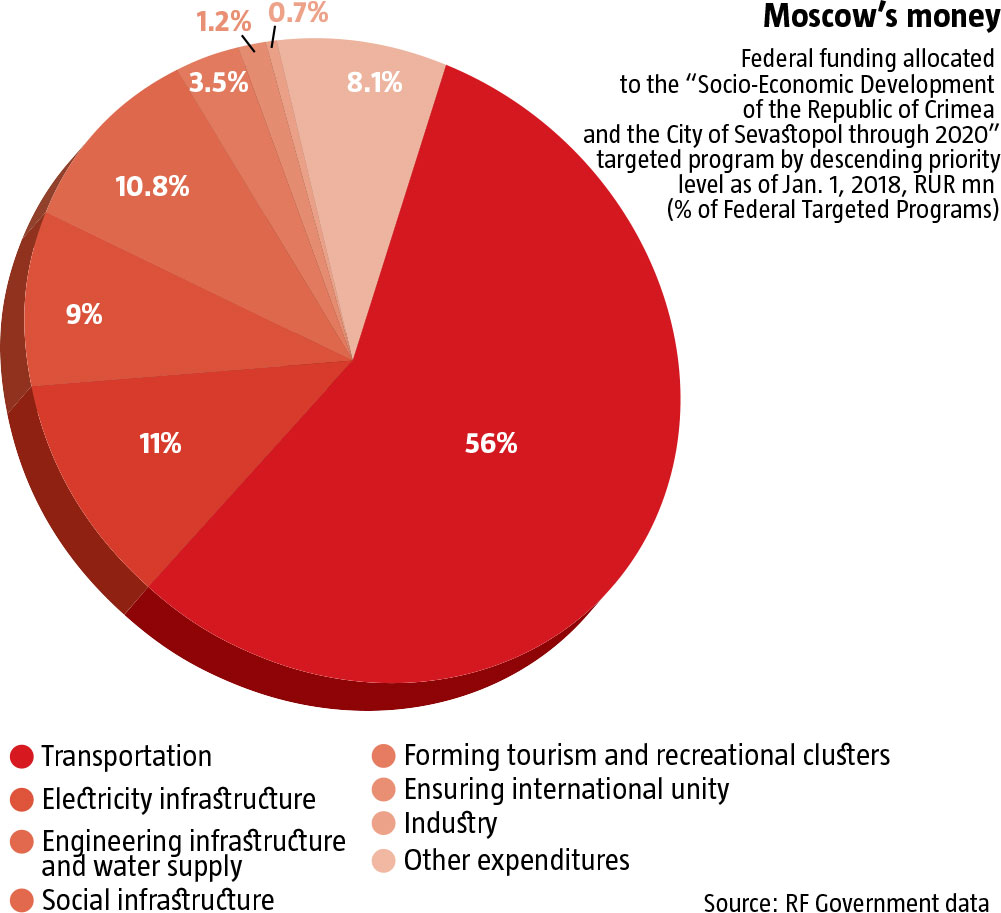

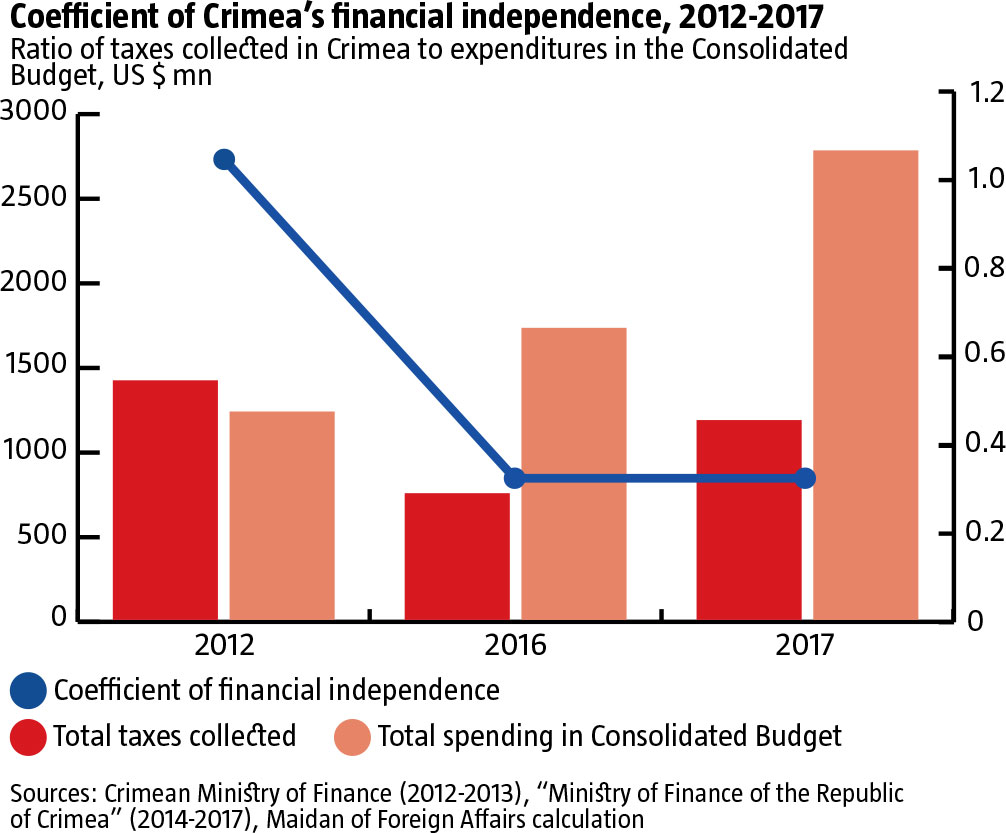

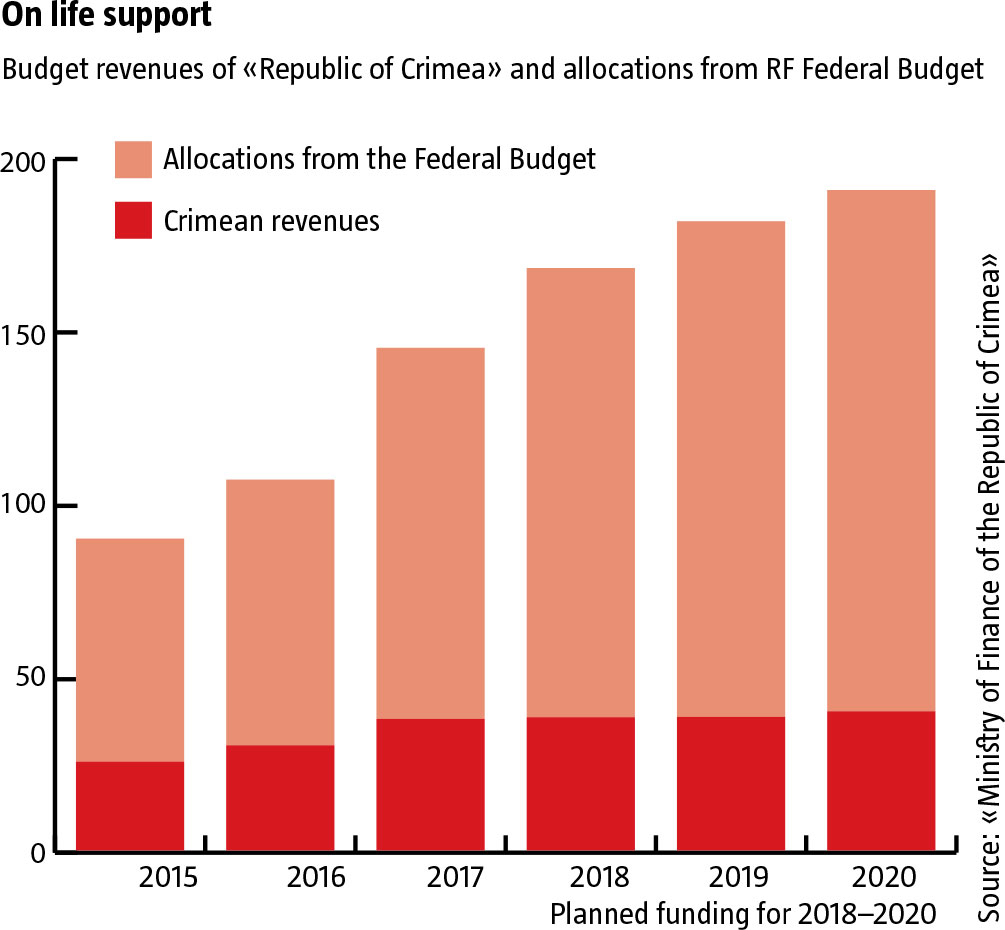

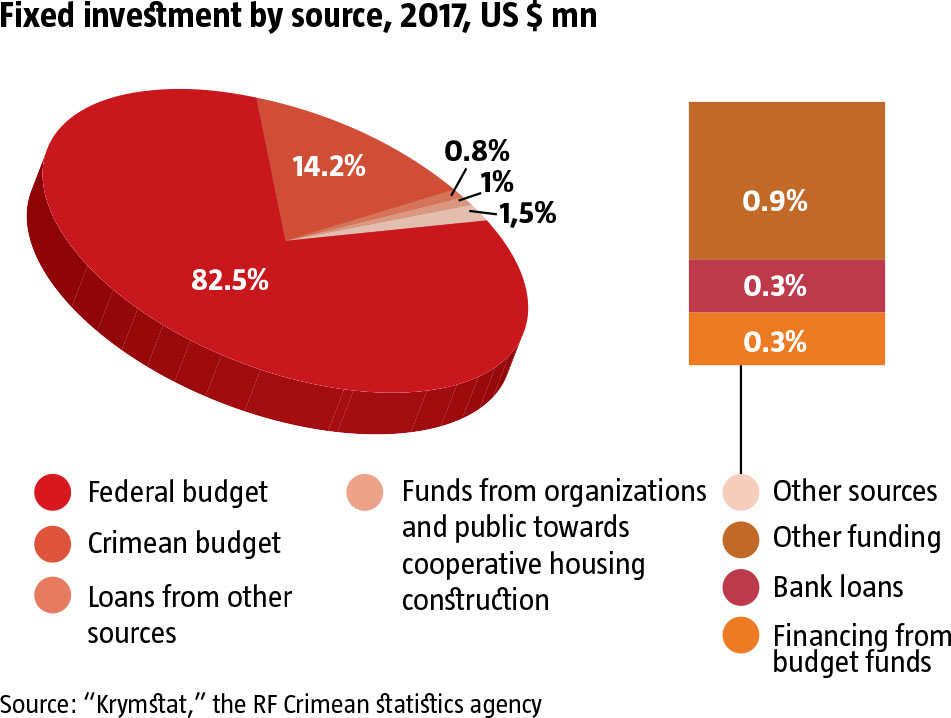

On August 11, 2014, the Russian Federation approved a targeted program called “Socio-Economic Development in the Republic of Crimea and the City of Sevastopol to 2020,” with a budget of RUB 669,594,630,000 or US $9.8bn, 95.9% of which was coming from the federal budget. Clearly, the implementation of this program has determined the economic life of Crimea. Still, anticipation among Crimean collaborators that they would enjoy a “shower of gold” from Russia as a result of this was unfounded. By early 2018, more than 1,000 contracts had been signed under the program with the main executors worth nearly RUB 600bn. About half of these were with Crimean contractors, but their total value was only RUB 28bn, or 3.5% of the actual amount allocated by the program at that point. The lion’s share of the golden shower went to Russian firms, especially in terms of job generation.

Even in 2014, the allocation of funds from the federal targeted program (FTP) was very eloquent: more than 80% of the expenditures were intended for three gigantic projects—the Kerch Bridge, the Tavrida Highway from the Kerch Strait to Sevastopol, and two new power stations. 10% was left for social services about 5% for tourism, and 1.5% to “ensure inter-ethnic unity.” This illustrated Moscow’s priorities very visibly: developing the critical logistics and energy infrastructure for a huge military base.

Notably, the construction of the Kerch Bridge stopped construction of nearly all new roadways and bridges in Russia. In 2017, only 10 new roadways were built across Russia, other than this bridge and the Tavrida highway. There simply wasn’t enough money for anything more.

At the beginning of 2018, the total financing for this federal program was up to RUB 837,174,19,000, of which RUB 770,192,94 was capital investment. Based on Moscow’s priorities, the money is currently being allocated thus:

RUB mn, % of FTP

1) transportation: 469,957.52 56.12%

2) energy: 87,801.17 10.49%

3) civil engineering and water supply: 76,078.74 9.09%

4) social services: 90,659.26 10.83%

5) tourist and recreation clusters: 29,194.01 3.49%

6) interethnic unity: 10,248.93 1.22%

7) industry: 5,450.03 0.65%

8) mass communication links: 243.25 0.029%

What’s important to also remember is that investments in MIC enterprises in Crimea are being undertaken by Russian corporations outside of this program. The construction and reconstruction of defense facilities is also taking place outside the FTP as this comes from the Russian Defense Ministry budget.

The FTP funding is being expanded for a number of reasons, starting with the ruble’s nosedive against the US dollar. In addition, the FTP was originally drafted in a hurry and during its implementation, many aspects specific to Crimea became visible. For instance, the cost of the Tavrida highway grew from RUB 41.8bn to RUB 144.0bn.

From the very beginning, the implementation of the FTP was complicated, deadlines were missed, endless corruption scandals plagued it, and criticism from top officials in Moscow grew harsher. This led to a gradual replacement of the Aksionov puppet Crimean Government with administrators from Russia. By the end of July 2018, a proposition had been drafted up in Moscow to extend the FTP through 2022 and increase funding by RUB 37bn, to cover 55 facilities in Sevastopol and a further 85 in the rest of Crimea. The authors of the proposal predicted that the FTP would be extended at least another 3-4 years with funding increasing in line with this. The most serious and long-term issue that needs to be resolved, both technologically and financially, is water supply.

The Kerch Bridge: Consolidating occupation

When the Kerch Bridge is completely open for traffic—trucks by the end of 2018 and trains at the end of 2019—, it will undoubtedly have serious military, political and economic consequences for Crimea. For starters, military logistics will be immensely simpler because trucks carrying men and materiel will be able to drive right in. After it finishes constructing the bridge, Russia will most likely be tempted to either close access from the peninsula to mainland Ukraine altogether—or make it as difficult as possible.

Over 2019-2019, the need for ferries to carry freight from Russia to Crimea will gradually disappear. But the remaining Crimean ports will continue to operate the way they do now, as an overflow system handling marine deliveries that don’t involve ferrying: grain, scrap metal and sodium carbonate to Syria, Lebanon, Libya, Egypt, Northern Cyprus, as well as glass, building materials and petroleum products from the Russian Federation, and cement and ilmenite from Turkey. Passenger traffic through Simferopol Airport will continue to shrink, the new terminals designed to handle over 7 million passengers a year will remain underused, and the investments made in them will not bring any returns.

Simplified road access could lead to growing flows of tourists to Crimea if the cost of vacationing on the peninsula becomes competitive for tourists from Russia. In any case, this is encouraging Moscow towards a policy of organizing vacations for low-income Russian citizens at Ukrainian sanatoria in Crimea that were expropriated by Moscow like so many spoils of war. RF civil servants, who are effectively prohibited to travel outside Russia, will also be encouraged to vacation in Crimea.

Banking

Prior to Russia’s takeover, Crimea and Sevastopol enjoyed a solid network of commercial banks, as 69 Ukrainian banks had branches on the peninsula. The RF planned to take advantage of Ukrainian financial institutions to ease the pain of the transition period, but none of Ukraine’s banks agreed to continue operations under the occupation. Major Russian banks that were already operating in Crimea prior to this, such as Sberbank, Alfa Bank and VTB, also stopped operations because of the fear of sanctions. This added another factor for certain foreign businessmen who, after visiting Crimea to test the investment waters, went into waiting mode.

Since the Russian occupation began, 34 Russian banks have launched operations in Crimea and two Crimean banks were transferred to Russian jurisdiction: Morskiy Bank, which belongs to Russian tycoon Aleksandr Annenkov, and the Black Sea [Chornomorskiy] Bank for Reconstruction and Development, which was “transferred” to the “Republic of Crimea” in September 2014. These are relatively small banks that have little importance for the Russian financial system. Indeed, 19 have already lost their licenses, one bank went bust and one is in bankruptcy procedures. Four banks left the Crimean market on their own. As of August 1, 2018, 8 Russian banks were still operating on the peninsula, all of which are subject to international sanctions.

Tourism: Rapidly shrinking numbers

After it was annexed, Crimea turned into a resort only for Russian tourists. and the quality of tourists changed dramatically as well. Previously, Russian tourists tended to be from the middle or wealthier classes. Over 2014-2017, low-income Russians began to travel to the peninsula on discounted tours organized by their employers. Well-known sanatoria belonging to agencies such as the Defense Ministry, the SBU, the General Administration, the State Fiscal Service, the Presidential Administration, the Verkhovna Rada, and so on, were treated like military trophies and passed on to their Russian counterparts, which proceeded to send their staff on holidays there.

Over 2010-2013, every tourist in a Crimean sanatorium was matched by four tourists in mini-hotels and rental apartments. Because of this growth, the tourism industry generated a substantial multiplier effect, as much as 3.5-4.0, in other branches of Crimea’s economy. In other words, for every UAH 1 in taxes paid directly by sanatoria, B&Bs and hotels led to UAH 4 in taxes paid by shops, services, entertainment places, transport, and by locals who served the tourists. Over 2014-2017, this correlation between tourists in major hotels and in the private sector shifted to 1:1.5.

In addition, the Ukrainian government’s easy approach to small tourist businesses to gradually bring them out of the shadows was replaced by threats and fines. Much higher taxes on land and property forces many hoteliers to quit the business as mandatory contributions to the Russian budget grew tenfold over the last four years.

In fact, resorts have already stopped being one of the priority areas of the Crimean economy, both in terms of budget revenues and in the social sense. Any official quantitative assessments of tourism in Crimea today are not worth paying attention to, as they are largely propaganda. According to our estimates, statements that there are 5.2-5.5mn tourists a year now are two to three times larger than reality.

Small business in decline

Over 2014-2018, Crimean SMEs shrank considerably in number. At the beginning of 2014, there had been 15,553 working small private enterprises and 116,200 private entrepreneurs. As of July 1, 2018, there were 1,382 private enterprises, a more than tenfold decline, and 55,328 private entrepreneurs, less than half.

Unlike Ukraine, say Crimean entrepreneurs, Russia doesn’t have a simplified tax reporting system and has not reduced the number of inspections. Small business in Crimea has seen reporting requirements multiply, along with a huge number of inspections and an unforgiving system of enormous fines for the least violation. Prior to 2014, small businesses accounted for more than 35% of employment on the peninsula and this indicator was growing steadily. Today, they account for only 19.5%.

The decline of small business in Crimea is likely to continue. Practice has shown that entrepreneurship, free thinking and independent consciousness are antagonistic to the model of relations that operates in modern-day Russia.

Consumers: Big wages for select sectors only

One of the main slogans prior to the Crimean pseudo-referendum on March 19, 2014, was that wages, pensions and social benefits would rise considerably. Among those Crimeans who were drawn to Russia, the image of the standard of living in Russia was shaped by watching TV shows based in Moscow and St. Petersburg, and by the servicemen in the Black Sea Fleet in Sevastopol, whose salaries were like per diems on international business trips.

Initially, these promises were held: starting in March 2014, salaries for government employees were paid in rubles at a higher-than-normal exchange rate. The coefficient used for calculating the exchange difference was 3.0 for commercial entities, which was the actual exchange rate then, but public sector salaries and pensions were calculated at RUB 3.80 to the UAH, a kind of “reward for betrayal.”

In 2014, food products on the shelves of Crimean stores were still mostly Ukrainian-made, inexpensive and of good quality, so the first year, pensioners, officials, teachers and doctors saw their buying power go up. But by the beginning of 2015, the Russian system began to be used to calculate wages and pensions. Meanwhile, Ukrainian goods began to disappear from shelves, to be replaced by costlier Russian equivalents, and eventually deliveries from the mainland stopped altogether when activists set up a blockade at the end of 2015 and the Government of Ukraine changed its policies.

By 2016 it was obvious that Russian salaries and pensions were actually a lot smaller than “advertised” in 2014. Between the higher prices for Russian goods and the steep decline of the ruble in the aftermath of Russia’s aggression against Ukraine completely wiped out the illusory effects of 2014. An additional complication affecting the social status of Crimeans was a decline in the real number of jobs available to locals because of an influx of workers from nearby Russian provinces.

RELATED ARTICLE: The occupied legacy

A look at discussions about salary levels in Crimean forums suggests that the average nominal salary in Crimea in 2016-2017 was in the range of RUB 10,000-15,000, although official statistics say it was close to RUB 25,000. Many public sector employees get around RUB 8,00-12,000. The exceptions are officials in government offices, police, military personnel, and workers in prosecutors’ offices, the judiciary and the military-industrial complex, whose salaries are 5-10 times higher than the average in Crimea. Meanwhile, the average pension was RUB 11,000-12,000 in 2016-2017. In fact, most pensioners get only RUB 10,000.

Our analysis also showed that, compared to 2014, the consumer basket had inflated by 75.16% in ruble terms by 2017 and 154.79% in hryvnia terms based on the exchange rate. All told, the buying power of the Crimean monetary unit in relation to the consumer basket has shrunk eightfold since the peninsula was occupied.

Based on salaries and pensions, Crimea has turned into an ordinary Russian backwater with a low standard and quality of life. As nominal salaries go down while priority sectors, as Russia defines them, see their salaries go up and up, Crimean society will polarize more and more between highly-paid Russian workers and the original residents of the peninsula, who will watch their capacity to purchase systematically shrink.

By Andriy Klymenko and Tetiana Huchakova, Yalta and Kyiv, Crimean Department of the Maidan of Foreign Affairs

Translated by Lidia Wolanskyj

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook