The recent campaign to discredit and dismiss Valeria Hontareva appears to be based on speculation, rumor, fear-mongering, unverified “facts,” open manipulation, and half-truths. It all started with a pamphlet entitled “Gontareva: A threat to the economic security of Ukraine,” which was distributed by MP Serhiy Taruta, the co-owner of the Industrial Union of Donbas (ISD), at the annual meeting of the IMF in October in Washington. From there, the epicenter of the campaign moved to Ukraine. Within a few weeks, a considerable number of articles appeared in public containing both reasonable arguments “pro” and “con,” and purely emotional rants. Now that all the sides have had their say, it’s time to analyze the arguments.

Forces majeures and more

After the Euromaidan and the Revolution of Dignity, a series of tectonic changes took place in the country’s economy, most of them with negative consequences. Many of them are now being blamed on the NBU and its governor, Valeria Hontareva. The biggest charge is over the steep devaluation of the hryvnia. Ukraine’s Constitution does make the National Bank responsible for the stability of the national currency and its latest decline affected absolutely all Ukrainians, without exception. But is the NBU at fault for this devaluation?

The exchange rate is based on the interaction between supply and demand on the currency market. The supply of dollars is determined by dollar earnings, primarily from export operations, and to a lesser extent from repaid credits, direct investments, transfers from migrant workers, and so on. Over 2014-2015, Ukraine’s exports plunged by 46% compared to 2013, and the country lost nearly US $40 billion in annual dollar earnings. Nearly US $12bn of that is the loss of exports to Russia and another US $2-3bn losses of exports to other CIS countries because Russia blocked their transit. The annexation of Crimea and the occupation of parts of Donbas cost another US $5-6bn, and if we include the disruption of production links, this amount probably doubles. In other words, from half to two thirds of the loss of exports in the last three years is directly due to Moscow’s actions, for which Ukrainians can thank Vladimir Putin and his fifth column in Ukraine, not Governor Hontareva.

The exchange rate is based on the interaction between supply and demand on the currency market. The supply of dollars is determined by dollar earnings, primarily from export operations, and to a lesser extent from repaid credits, direct investments, transfers from migrant workers, and so on. Over 2014-2015, Ukraine’s exports plunged by 46% compared to 2013, and the country lost nearly US $40 billion in annual dollar earnings. Nearly US $12bn of that is the loss of exports to Russia and another US $2-3bn losses of exports to other CIS countries because Russia blocked their transit. The annexation of Crimea and the occupation of parts of Donbas cost another US $5-6bn, and if we include the disruption of production links, this amount probably doubles. In other words, from half to two thirds of the loss of exports in the last three years is directly due to Moscow’s actions, for which Ukrainians can thank Vladimir Putin and his fifth column in Ukraine, not Governor Hontareva.

Since 2014, prices for commodities have been falling on global markets, which has eaten up about US $4-5bn of the remaining amount. And world trends are not something the National Bank of Ukraine has a lot of influence over. Finally, the country inherited a trade deficit of about US $15.6bn from the Yanukovych regime, which meant that the hryvnia exchange rate was inflated even before the Euromaidan and needed to be adjusted downward.

All told, Ukraine suffered an unprecedented decline in exports and this meant that dollars were in short supply on the domestic money market. Capital flight, money taken out of the country by members of the previous regime who figured they were unlikely to be able to enjoy their ill-gotten gains at home in the future, and the panicky actions of contractors who were afraid of the war and of the losses that it would bring, all led to a steep rise in demand for hard currency. The supply shrank as demand grew.

These are the factual reasons why the hryvnia lost value: they did not depend on the NBU and the Bank could not have done anything to prevent them. The only thing it might have done—and eventually did—, in this situation, was to institute strict controls over the currency market. Even so, some quarters complained about these controls and about their side effects, blaming the central bank and Hontareva personally.

Damned if you do, damned if you don’t

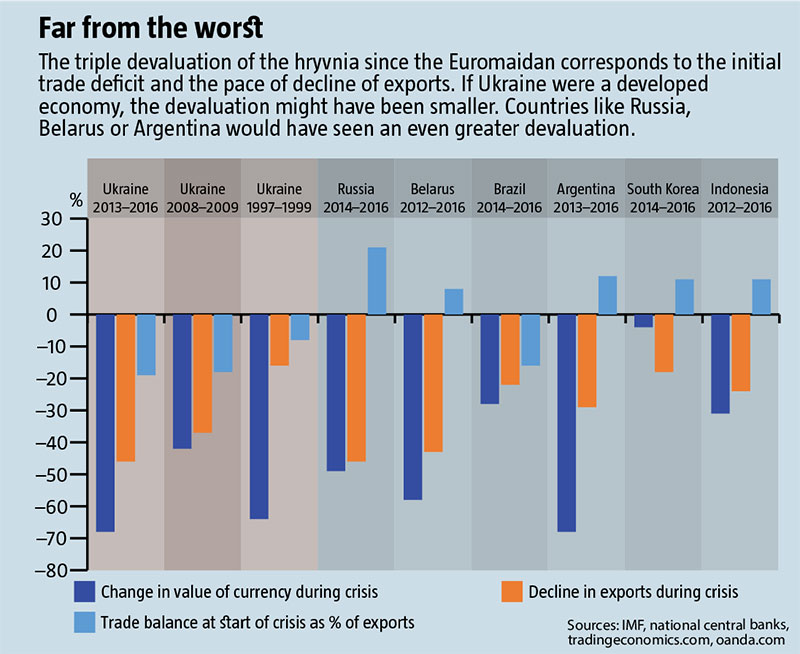

What about the size of the devaluation—was it too steep? If Ukraine’s balance of payments crisis of the last three years is compared with other countries (see Far from the worst), it appears that it was not. The Russian and Belarusian rubles collapsed by more given their initial trade surpluses and the size of the foreign exchange reserves of the Russian central bank. In developed countries, devaluations were relatively lower, but even their systems weren’t much more stable. The devaluation of currencies in countries that went into unexpected default, such as Argentina in 2014 and Ukraine at the turn of the century, was more substantial.

Ukraine was able to avoid a collapse in its currency because of the rapid response and negotiating skills of the Ukrainian team at the time, some of whom were from the NBU, with foreign creditors. Over 1997-1999, the newly-minted hryvnia also devalued by two-thirds, going from UAH 1.76/USD to UAH 5.00/USD and Ukraine managed to restructure its public debt successfully. The then-governor of the NBU, Viktor Yushchenko was appointed Premier at the end of 1999 and no one even considered blaming him for the devaluation of the hryvnia that he had so successfully introduced in September 1996.

In short, with the national currency losing value for external reasons, the NBU did what it could, which was to establish strict controls, increase the interest rate and so on. By not succumbing to provocations and numerous calls to print more money to finance government bonds, it managed to prevent a far worse situation from developing.

RELATED ARTICLE: Lessons learned: The benefits and flaws of PrivatBank nationalisation

In terms of the exchange rate, there are two factors that can be laid at Hontareva’s feet. The first was artificially propping the rate prior to the Rada elections in October 2014 when the war in Donbas was going full-force. The second was specific statements that there would be “no further devaluations” and that the dollar would “stop”—first it was UAH 12, then UAH 16, and then UAH 20. But neither of these factors had much of an impact on the overall result of devaluation.

The NBU governor is also being blamed for the sharp rise in inflation, although inflation is a direct consequence of the devaluation of the hryvnia, because the proportion of imported goods, from medicine and clothing to fuels and so on, is high. Devaluation also affects the value of utilities, whose rates are set by the Cabinet. If the hryvnia were stronger, rates would be lower, so blaming the Bank is simply wrong.

Indeed, the National Bank can be thanked for the fact that, in just one year, it was able to bring consumer inflation, which had peaked at 60.9% in April 2015, down to 10%. Appropriate, strict monetary policy gave the necessary results. Without that, inflation would continue to trample the wallets of Ukrainians. The NBU simply did what it could in very difficult circumstances that it found itself. Yet Governor Hontareva is also being blamed for the decline in household incomes and in the standard of living—both of which are the plain arithmetic result of inflation and devaluation.

Cleaning the Augean stable

One major accusation against the central bank is the removal of more than 80 commercial banks from the market. Is this a large number or not? According to the FDIC, the US deposit insurance fund, 25 financial institutions left the market during the crisis of 2008, another 142 closed down in 2009, a further 157 in 2010, and 92 in 2011. Of course, the US has over 5,000 banks, but the system is much better regulated and reliable, and the Federal Reserve works more systematically and effectively. Moreover, the crisis of 2008-2009 was not nearly as deep as what Ukraine has experienced. And even so, cleaning up the fallout from the crisis took more than three years.

According to Russia’s central bank, 76 banks lost their licenses in 2014 alone, as well as a dozen non-banking lending institutions. Another 102 lost their licenses in 2015 and a further 81 were stripped during the first three quarters of this year. A total of 600 remain, which means a third of the sector has disappeared. True, Ukraine’s share of bankrupt banks is larger, because, after the 2008-2009 crisis, Russia’s regulator cleaned out the system, shutting down 137 banks over 2008-2010. Had the NBU done its job after the crisis rather than preserving pseudo-banks and the status quo, it would have had a lot less work to do today. The fact that Hontareva took this task on, without any pressure from the IMF, simply honors her.

But there are two minor quibbles. Firstly, the NBU supposedly could have saved about a dozen of those banks. Perhaps so. But how would that have changed the overall picture? At the current stage, the regulator needs to demonstrate enough firmness that the country’s bankers will believe in its integrity and resolve to make the banking sector better. And this occasionally means resorting to draconian methods. The second complaint is that the insolvent banks lost about UAH 30bn in refinancing and over UAH 100bn belonging to individuals and businesses. This particular side-effect is society’s inevitable price for the clean-up.

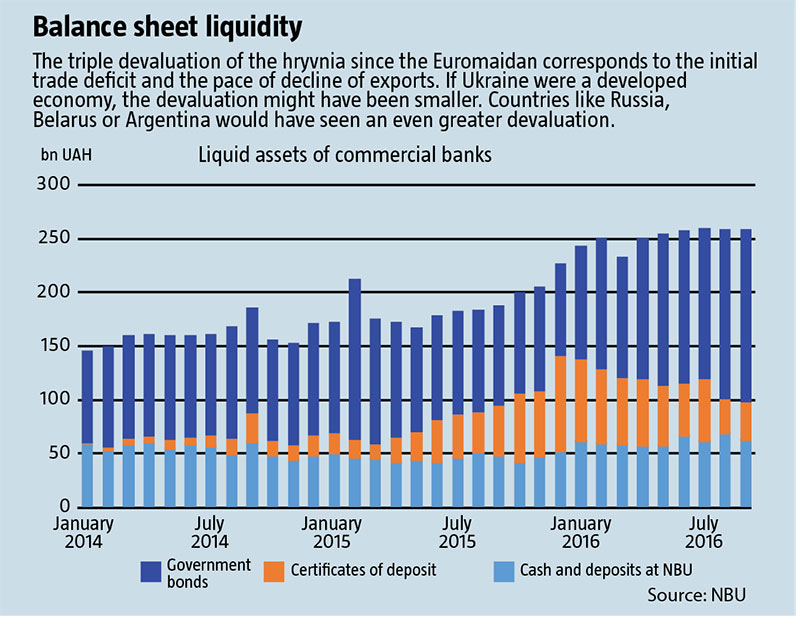

One more accusation is that domestic banks have supposedly stopped lending since Hontareva became the NBU governor. Yet the NBU kept lowering the prime rate over 2015 and 2016: from 30% in March 2015 to 22% that September, then to 19% in April 2016, and 14% in November. And in the last 6 months, banks are enjoying record levels of liquidity. The reason they aren’t lending, however, is because of the crisis. At the moment, it’s more profitable for them to make 12-14% on certificates of deposit or 16-18% on government bonds than to lend money that might never be repaid, even at 20%. In QI’09, banks also stopped giving out both commercial and personal loans, but that crisis was short-lived and by the third quarter, commercial lending had picked up again. Individuals, however, are still paying off personal loans from that time. In fact, loan portfolios have not grown during crises in Greece or other problematic European countries, either, because it’s too hard to assess the cash flow of potential borrowers. Ukraine is no exception in that.

More serious accusations against Valeria Hontareva derive from her pre-NBU years. For instance, she ran Investment Capital Ukraine (ICU), a company that is criticised for helping the Yanukovych “Family” to rob the state. Recently published documents shed some light on this situation. ICU was involved in the schemes publicized recently that were used to embezzle from state banks on the Perspektyva stock exchange, which the Family controlled. ICU acted as the official intermediary between a state bank and the “pocket” money-laundering operation known as Fondoviy Aktyv (FA) or Equity Stock and was paid a standard commission for its services, not a cut of the deals. Both FA and the Perspektyva exchange, and the supervisory boards and top management of the state banks belonged to the Donetsk clans who were happy to enjoy this windfall and had no intention of sharing it with anyone.

RELATED ARTICLE: Economic potential of Ukraine's sea ports

Could Hontareva and the company she ran have not taken part in these schemes? Without any doubt. At the time, the company was one of the leaders in this segment of the market and professional market players were needed as an intermediary, in accordance with the law. In fact, such schemes could not have been carried out without companies like ICU, although what ICU itself did involved absolutely legal operations. Did Hontareva know about the entire scheme and its possible consequences? Apparently, yes. The publicized documents show that ICU not only bought and sold T-bills, but also participated in driving up prices on these bonds, that is, deliberately overpricing them so that the Family wheeler-dealers could take advantage of them later.

Ultimately, this is a moral issue. Knowing the nature of these schemes and their ultimate purpose, an honest person should have refused to be involved. In recent years, many companies were involved in driving up prices for shares and bonds, including junk bonds, in an effort to plug the holes that had appeared in their balance sheets after the 2008-2009 crisis. Whether IСU’s willingness expose stock exchange schemes will have a positive impact on the market remains to be seen

A much more damaging accusation is that money was taken out of Delta Bank by Hontareva’s relatives prior to the bank being declared insolvent. Whether this accusation is based on fact or not, Ukrainian banks are known for this widespread practice: insider knowledge is used to remove money from a bank that is about to go into temporary administration. Typically the bank’s biggest clients are offered deals to recover their money for a cut, sometimes as much as 50% of the cash. The problem is that the National Bank is structured in such a way that it is very easy for certain individuals to buy the information they need. And it is a problem Hontareva had better deal with without delay.

One accusation concerns the removal of assets from the NBU’s Corporate Non-state Pension Fund (KNPF). The purchase of junk stock and government bonds of a company called Svizhachok and others like it with the knowledge of NBU management took place at least five years prior to Hontareva’s appointment. In fact, she initiated an investigation into this affair when she came to the Bank.

As governor of the National Bank of Ukraine, Hontareva must now look at changing the system to make it impossible for money to be withdrawn on a massive scale and effectively embezzle the Fund to Guarantee the Deposits of Physical Entities (FHVFO). Results won’t be immediate and will need the cooperation of the Fund itself and of the Verkhovna Rada. The same goes for the NBU’s Corporate Non-State Pension Fund, which should operate in a standard manner and not be hand-managed by the Bank. Criticisms of the NBU’s flawed system are fair, and hopefully Hontareva is prepared to do something about it.

RELATED ARTICLE: How the life of Ukrainians changed over the past 25 years economically

“Fostering a Russian expansion”

Hontareva has also been blamed for allowing the expansion of Russian banks into Ukraine. Today, there are seven Russian institutions in Ukraine: the state savings bank Sberbank Rossiyi, Alfa-Bank, Prominvestbank, VTB, VS Bank, BM Bank, and Forvard Bank, formerly known as Russkiy Standart. According to NBU data, their share of assets among 182 banks operating in Ukraine was 10.8%. By mid-2016, with only 101 banks operating, their share had inched up to 12.2%. Recently, UkrSotsBank/Unicredit was bought or merged with Alfa-bank, which would raise their share to 16.3%

Still, given the serious decline in the number of banks on the Ukrainian market, the Russians should have gained a lot more market share if they were expanding. For instance, PrivatBank has increased its market share from 16.8% to 21.4%, while Oschadny Bank has increased its share from 8.1% to 14.7%. After the Euromaidan, Ukrainians began to massively boycott Russian goods—and Russian banks felt the hit as well, losing deposits at the fastest rate of any other domestic banks.

There is, of course, the question why no Russian banks have lost their licenses, although Prominvest and VTB bank are known to have plenty of problems and gaps in their balance sheets. Others are probably also less than ideal. It’s hard to know whether these banks are simply staying within the law or whether the issue of Russian capital in Ukraine was one of the unpublicized components of the Minsk talks. In any case, it’s an issue that would be better addressed to the National Security Council or to the President rather than the Governor of the National Bank.

Job 1: Credibility

One odd item in the Taruta brochure is the statement that trust in the NBU governor is only 2.8%. Given the threefold decline in the hryvnia against the dollar, this is hardly surprising, but in fact, the reasons for the devaluation are something at most 10% of Ukrainians actually understand. And it hasn’t been helped by massive criticism aimed at Hontareva on oligarch-owned television channels and the months-long pickets of “deceived depositors” in front of the NBU and Parliament.

Clearly, she has stepped on some big toes of Dmytro Firtash, Kostiantyn Zhevago, Oleh Bakhmatiuk and Serhiy Arbuzov, one of her predecessors, as well as other Family members, by withdrawing the licenses of many of their banks. Ihor Kolomoyskiy has probably joined their ranks now that the regulator is forcing him to stop using PrivatBank to finance his other businesses. So it’s no surprise that many television channels have little good to say about the NBU these days, because that might increase confidence in both the hryvnia and Hontareva.

RELATED ARTICLE: The scale and impact of monopolisation in Ukraine's economy

Meanwhile, certain politicians are trying to make populist hay out of the situation and piling on the criticisms. But confidence is not just an official “measure of popularity.” The NBU today has a proper team of professionals and is working to institute best world practice in its administration. Indeed, international and independent Ukrainian experts say that the National Bank is one of the leading reforming institutions in Ukraine today and give it high marks for its work. So, when the Rada submitted a series of bills intended to reduce the NBU’s powers and make it more amorphous, the IMF and others came to the defense of the independence of the central bank.

The NBU’s first female governor has certainly made her fair share of mistakes, both before being appointed to the Bank and since. But those mistakes pale in comparison to what Hontareva has accomplished and the major problems she has managed to avoid. At this point, it makes more sense to let her to carry through the reforms that she has begun rather than pushing for her to be dismissed. The oligarchs have not been happy with the slew of new people who have come to government, are taking reforms seriously and are working to establish rule of law—and the populists and fifth columnists are quite happy to jump on this bandwagon. At a time when the country is slowly but surely crawling out of an economic black hole, however, preserving the credibility of the central bank should be a priority.

Translated by Lidia Wolanskyj

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook