The whirlwind of the latest "great migration of peoples", which has spread to more and more countries in recent decades, is rapidly approaching Ukraine. On this path, we will have to face challenges that other countries have already experienced in the past or continue to experience. However, we have the chance to avoid falling into the same traps that they did. Instead, by taking advantage of the latest technological and socio-economic trends from around the world, we can account for the experience of others and avoid many challenges they have encountered or will face in the near future.

Neglected by Their Own

Starting from the early 1990s, Ukraine primarily entered the era of the "great migration" as a donor country – a huge part of the population rushed to other countries and even other continents in search of a better life on a temporary or permanent basis. The Ukrainian emigration of the 1990s and early 2000s was aimed primarily towards remote places in Western Europe and North America. Even those migrants who did not dare admit to themselves that they were never going to return rarely visited their homeland due to objective financial and geographical reasons. Instead, they gradually enticed friends and relatives to their new lands.

The second wave of Ukrainians searching for a better fortune outside their native land began relatively recently and continues to this day. A new characteristic is that illegal immigrants are fewer and farther between, as they take advantage of the charms of the visa-free regime and liberalised regulations for migrant workers in new EU member states. On their part, these countries feel a strong effect from the massive outflow of their own citizens that work in richer countries of the Schengen Zone. This wave of migration carries out a much higher amount of trips back and forth and has a much larger seasonal component than was the case in the 1990s and early 2000s. Our compatriots focus mainly on EU countries located next to Ukraine. Nevertheless, the proportion of those there who are no longer considering a return to their native country to look for a job is growing.

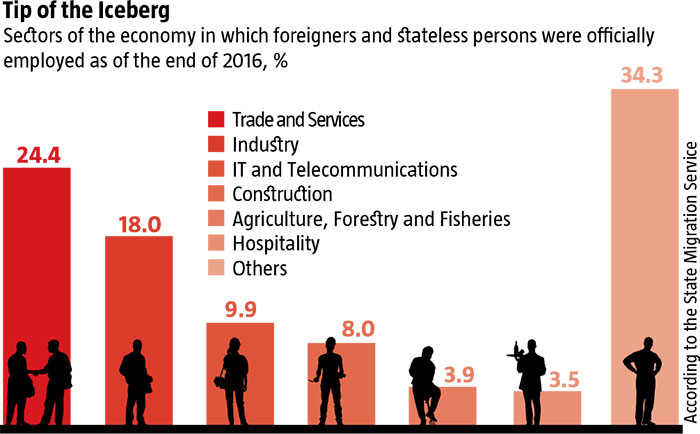

In the short term, the current wave of massive labour migration from Ukraine could have a much larger influence on the domestic labour market. While the National Bank of Ukraine, as vice-chairman Dmytro Solohub recently said, rejoices in its positive impact for balancing the demand and supply of foreign currency in the country (this year, payments from labourers are expected to reach $11.6 billion and then at least $12.2 billion next year), this coin has two sides. Gaining ever-greater magnitude, this process exacerbates the shortage of workers in a number of sectors of the Ukrainian economy, while at the same time stimulating the demand for goods and services from the relatives of emigrants, in addition to some of the migrant workers themselves, depending on the season. However, as worker shortages are uneven across industries, the rapid increase of demand and much slower wage growth in the respective sectors have recently been compensated for not by retraining personnel from other parts of the national economy or the unskilled unemployed, but by gradually filling the corresponding niches with immigrants from other countries that are significantly poorer than ours and whose inhabitants find it ever more difficult to get into the EU.

Ukrainian statistics clearly confirm that the key factor behind the rapid growth of labour migration to EU countries is not a shortage of jobs or an increase in unemployment in the country, but the desire for higher earnings from those who could easily find work in their homeland. After all, in recent years the rate of reduction in the number of jobs in Ukraine has sharply slowed down even when compared to the pre-war years of 2010 to 2013. Internal migrants, particularly in the construction sector, increasingly demand wages at the same level as in neighbouring EU countries, since "it makes no difference" where they work – in the main economic centres of Ukraine, Poland or the Czech Republic. At the same time, the labour supply on the domestic market is also rapidly decreasing for natural reasons: the generational structure is deeply asymmetrical. People born during the demographic pitfall of the late-1990s early-2000s are joining the workforce while the much more numerous generation of post-war 1950s baby boomers are leaving it. There is more than a twofold difference in size between them. For example, in 1950 and 1960, 840,000 and 870,000 people respectively were born in Ukraine, but only 385,000 in 2000. Considering that a significant part of this young generation leaves the country either as labour migrants or as part of the growing number of foreign students who, for the most part, do not plan to return either, there is only one working-age Ukrainian joining the domestic labour market for every three or four older citizens that are retiring. Youth unemployment is either due to regional differences and/or much higher expectations than employees are willing to offer within the current economic model.

Attractive to Others

At the same time, the flow of foreigners to Ukraine, mostly from Asian countries, continues and is even slowly growing, while immigration from Africa has picked up too. Africans have actively started to look for a place to apply themselves more effectively due to the demographic explosion, increase in unemployment, limited natural resources and, above all, scarce food on their home continent. There are at least 5-6 channels for such migration. They include studies in Ukraine that end with a desire to stay there, additions to large family clans that have already settled in the country through family reunification or marriages and hiring illegal immigrants to work in retail, services or manufacturing in the shadow economy. All the way up to attempts to obtain refugee status in Ukraine, unsuccessful attempts to reach the EU through the country and those smuggled by rare but aggressive ethnic criminal groups.

Official statistics show that since 2005, Ukraine has seen a steady increase in migration. That is to say, the amount of those officially moving there exceeds the number of people that have left the country. According to official figures, this amounts to about 15,000 people annually, which has for years compensated the 5-8% natural population decline due to the fact that the mortality rate in Ukraine is higher than the birth rate. Every year, at least 20-30 thousand immigrants arrive in the country. In total, almost 265,000 people were officially registered as immigrants with the State Migration Service at the beginning of 2018. In 2015, 16,700 official immigration permits were issued, in 2016 15,100 and 15,700 in 2017. In addition, tens of thousands of foreigners annually receive official temporary residence cards or have their current documents prolonged. The number of permanent and temporary residence cards given to foreigners in Ukraine is growing year on year too: about 83,000 in 2015, around 89,000 in 2016 and almost 94,200 in 2017. From 2015-2017, the State Migration Service issued 81,600 permits for permanent residence alone.

According to the official State Statistics Service, the majority of immigrants are people from Asia and Africa. For example, out of the 280,600 that arrived in Ukraine from 2010 to 2016, 162,200 (58%) came from those two continents. Moreover, in 2016 their share exceeded 74%, although it was less than 37% in 2011. To be more precise, between 2010-2016 22,100 people from Africa migrated to Ukraine, 16,400 from Turkmenistan, 12,800 from Azerbaijan, 12,000 from Uzbekistan, 6,100 from other Central Asian countries, 7,500 from Georgia, 7,200 from Turkey and 5,900 from Armenia. The fact that Ukraine has an unlimited visa-free regime with all states in the Caucasus and Uzbekistan contributes to this geographical spread: their citizens can even remain in the country all year round. In recent years, the share of immigrants from Africa has sharply increased from 10.5% of all immigrants in 2015 to 16% in 2016 (the 2017 data on countries of origin has not yet been disclosed). In 2010-2011, they represented less than 1% of all arrivals. Most other immigrants hail from the Russian Federation, especially from poorer regions and the North Caucasian republics. From 2010 to 2016, 87,600 of them moved to Ukraine – 31.2% of the total flow of immigrants over this period. However, following the start of the Russian aggression, both the total number and the share of Russian citizens declined, and by 2016 they accounted for less than 24% of all legal immigrants. As for officially recognised refugees in Ukraine, more than 57% are from Afghanistan.

At the same time, the lion's share of foreigners settled in Ukraine are young men and women. For example, in 2016, according to the State Statistics Service, men aged 15-34 made up 44% of all immigrants and more than 65% of male immigrants, while women of the same age represented 17.3% of all immigrants and more than 52% of immigrant women. Many of them have already given birth to children in Ukraine, who in turn legally receive citizenship. Indeed, according to current legislation, a comprehensive list of children of foreigners and stateless persons has the right to obtain citizenship. More precisely, it is awarded "by territorial origin" to children who "were born on the territory of Ukraine after 24 August 1991, did not acquire Ukrainian citizenship at birth and are a stateless person or a foreigner". Or "by birthright" to those who "were born on the territory of Ukraine to stateless persons legally residing in Ukraine", "were born outside of Ukraine to stateless persons permanently residing legally in Ukraine and did not acquire the citizenship of another state at birth"," were born in Ukraine to foreigners legally resident in Ukraine and did not acquire the citizenship of either parent at birth", "were born in Ukraine, have one parent who has been granted refugee status or asylum in Ukraine and did not acquire the citizenship of either parent at birth or acquired the citizenship of the parent that has been granted refugee status or asylum in Ukraine", "were born in Ukraine to a foreigner and stateless person legally resident in Ukraine and did not acquire the citizenship of the foreigner at birth". Data from the State Migration Service indicates 11,200 people gained citizenship by birth or territorial origin in 2014, 10,300 people in 2015, 14,600 in 2016 and 20,200 in 2017. This includes 4,700 by birthright in 2014, 6,600 in 2015, 10,600 in 2016 and 16,600 by 2017. As we can see, there was an almost 3.5-fold increase in just 3 years. The total number of people to acquire citizenship "by birthright" over these four years was 38,500, and if we include those "by territorial origin" this figure grows to 56,300. Additionally, in a number of immigrant communities the practice of marrying women from their countries and ethnic communities of origin is widespread, which, in turn, creates another sizeable channel for obtaining the right to live in Ukraine on an official basis. According to State Migration Service data, invitations for the entry of foreigners and stateless persons are an important source for replenishing the ranks of immigrants in Ukraine (11,100 in 2014, 15,900 in 2015, 19,800 in 2016 and 5,900 in 2017).

Additional measures to restrict the flow of immigrants to EU countries that are currently being developed could significantly increase the attractiveness of Ukraine. According to the State Customs Service, in only five months (January-May 2018), more than 4,000 illegal migrants were discovered in Ukraine – and those are only the officially documented cases. To make it clear, this is only 10-11 times less than the amount of illegals found in the entire EU over the same period. In total for 2017, more than 9,700 illegal migrants were discovered in Ukraine. At the same time, several hundred violators of Ukrainian legislation on the legal status of foreigners and stateless persons are caught every week in the country. It is obvious that in all these cases we can only see the tip of the iceberg as far as illegal immigration and violations of legislation on the residency of foreigners is concerned. The bulk of it remains imperceptible to government agencies, or is at least not reflected in their official documents. After all, turning a blind eye to illegal immigrants has long been a profitable business that compensates for the rather modest official incomes of the public servants responsible for this field.

Learn from Others' Mistakes without Repeating Them

As we see, the dynamic growth of the number of immigrants in Ukraine, even despite the unfavourable socio-economic situation in the opinion of many Ukrainians, indicates a high probability that we will increasingly follow the "great migration of peoples" model in the near future, according to which richer new EU member states (Poland, Lithuania, Czech Republic) and poorer old ones (Spain, Italy, Portugal) have been developing for quite some time. In 2016, 2,800 official residence permits for employment alone were issued and 4,700 in 2017. If everything develops according to the baseline scenario, this could be boosted by ever more active lobbying from Ukrainian employers. After all, the Party of Regions proposed a strategy of "simple" ways to solve the problem of labour shortages in the main economic centres of the country during the post-crisis economic recovery of 2010-2011. Migration was suggested by both Deputy Prime Minister Serhiy Tihipko and former trade union leader Oleksandr Stoyan, who announced in spring 2011 that "by the end of the year we will have to bring in people from abroad, because we will not have enough workers". Although the next crisis and then the war interrupted the implementation of these plans at the state level, the quiet influx of migrants to Ukraine has been continuing for a long time and is gradually gaining momentum.

However, building a strategy by going down the same road as a number of European states – filling vacant jobs with foreigners – would be disastrous. The West is already moving away from it due to the obvious challenges and threats caused by a massive influx of foreigners from another cultural and civilizational environment that are not prepared to integrate. In Ukraine, these challenges are complemented by the specifics of the country. After all, the main places where foreign migrants are currently concentrated are cities in the South East and, to a lesser extent, the Centre and other regions with the highest rates of natural population decline and ageing. For example, according to the State Statistics Service, in 2016 more than 83% of all immigrants were located in cities – usually the largest in the country or their surrounding areas. According to data from the State Migration Service, the lion's share of illegal immigrants are found in the main economic centres of the country – more than 17% for the first five months of 2018 (15% in 2017) in Kyiv and the surrounding region, 14.5% (15.5% in 2017) in the Kharkiv Region, more than 11% (10.1% in 2017) in the Odesa Region and 10.5% (unchanged from 2017) in the Dnipropetrovsk Region and Zaporizhia.

In total, these regions account for more than half of all detected illegal immigrants. Since the Ukrainianisation of cities in the Centre, not to mention the South-East, leaves much to be desired, the new settlers, in the absence of an effective integration policy, will be Russified and replenish the ranks of the post-colonial masses that experience strong nostalgia for the Soviet past and are indifferent or even sceptical towards the Ukrainian state and its interests.

Gloomy Prospects

The immigration option for solving demographic problems also has a socio-economic aspect. If anyone believes that immigrants will pay Ukrainians' pensions and provide for their old age, they are deeply mistaken. Firstly, in all European countries, such migrants generally have not shown and continue not to show a desire to assimilate in the communities of the countries they move to. Secondly, they have no particular desire to pay taxes or spend their own hard-earned cash on maintaining high social standards in these countries. The role of family/clan relations is decisive in the majority of communities that supply potential migrants to Ukraine and they fulfil the basic functions of mutual assistance and support of socially vulnerable groups or the elderly. Therefore, they have the tendency to work within the corrupt model of the shadow economy, which is much more dangerous for Ukraine than for EU countries, as it already has serious problems with the phenomenon. Nevertheless, the migrants themselves often seriously suffer because of this.

Against the backdrop of the issues that Ukraine has been experiencing over the past decades, the high-tech discourse in economically developed countries can look like something verging on science fiction, as modern technologies reach us in limited quantities. Nevertheless, the Third Industrial Revolution is raging on. Recently, the prospects and challenges related to the transition to the Fourth Industrial Revolution with its robotic automation and artificial intelligence for managing production processes are being discussed more and more actively. As a result, the increasingly obvious consequence of the Third (not to mention the Fourth) Industrial Revolution is a serious reduction in jobs. Oxford University experts warn that by the 2030s people in developed countries will yield almost half of their jobs to artificial intelligence. Recently, British company Verisk Maplecroft, which specialises in risk management, released a report saying that 56% of current employees in the largest production centres of developing countries such as Vietnam, Indonesia, Thailand and Cambodia could lose their jobs in the next 20 years due to the increasing automation of manufacturing.

In the context of the technological changes that the world is moving towards, it is important for Ukraine to prevent a mass influx of migrant workers from Asia and Africa in order to compensate for the Ukrainians that have left for other countries. Instead, it is important today to send a clear message to Ukrainian businesses that cheap labour resources will not be brought in at any time either now or in the future. This should make them face the fact that it is necessary to aim towards the automation of production processes, make increasing preparations for an ever more expensive workforce, stimulate the development of skills and adapt to modern educational requirements. Without a clear signal that there will be no cheap labour, either Ukrainian or immigrant, this will not happen.

It is also important to realise that the Third and Fourth Industrial Revolutions, which are progressing at various speeds in different countries around the world, will have an influence – directly or indirectly – on Ukraine in any case. Reducing the number of jobs for humans and replacing them with robots and artificial intelligence in developed countries will first and foremost hit migrant workers, who will be the first people dumped out of the economy. Unlike local residents, they will have significantly less chances and opportunities to claim compensatory social mechanisms, such as the so-called basic income. Therefore, many of them will be forced to return home, triggering reversed movements of migrant workers compared to what has been observed so far. Former migrants will return from richer countries to their less affluent ones, which will be left by the people who immigrated there to replace them.

Since Ukraine risks being left holding the baby as part of this scheme, it is very important today that we do not allow ourselves to build an economic model for replacing workers with immigrants from other countries by inertia. With the current advantage that labour migration to our country has not yet reached the same scale as in other, richer European countries, there is a still chance to do a lot to ensure we suffer less as a result of automation. Our weakness that is due to the rapid natural decrease in labour resources mentioned at the beginning of this article could turn into an advantage. After all, fewer labour resources will mean fewer problems finding places for so-called superfluous workers when artificial intelligence and robots start to actively force humans out of the economy.

Translated by Jonathan Reilly

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook