Two years before the Lumière brothers, a remarkable event unfolded in the seaside city of Odesa—a “fine art exhibition of live photographs, moving with the help of an electric machine”—what we would now call a film screening—took place at a hotel named ‘France’ – oh, the irony! That evening, audiences enjoyed two films: The Horseman and The Spear Thrower, both filmed at a local racetrack. However, the Ukrainian inventor Yosyp Tymchenko, who developed the “kinetoscope” featuring a disc-based photo plate, never patented his invention. As a result, France still holds the title of cinema’s birthplace. Nonetheless, Ukrainian cinema in the 20th century, rooted in several film studios, emerged as a vibrant chapter in the global history of film. Let’s take a moment to explore the places and the filmmakers behind the films that future directors and cinematographers around the world now study.

Odesa Feature Films Studio: the cradle of Ukrainian cinema

First, it’s worth mentioning the film studio along the seashore on Odesa’s French Boulevard, which got its start in 1919 when several private studios merged together, each with their own sound stages. This merger wasn’t really by choice, as the private studios’ properties were nationalised, creating a state film studio that was initially linked to the Soviet Red Army’s propaganda department. By 1922, though, it was rebranded as the Odesa Film Factory under the All-Ukrainian Photo Cinema Administration (VUFKU), kicking off its “golden era.”

The studio’s success can be largely attributed to Yuriy Yanovskyi, often referred to as the “benevolent genius of Ukrainian cinema.” He was a talented writer, screenwriter, and the studio’s editor-in-chief starting in 1926. A master at making connections, Yanovskyi quickly brought some of the finest writers of the time to the Black Sea city to craft scripts, including Isaak Babel and Mykola Bazhan, along with actors like Amvrosii Buchma and Yuliya Solntseva. However, the standout talent was the then-unknown Oleksandr Dovzhenko, who would go on to become a brilliant director. Encouraged by Yanovskyi, who believed in his friend’s talent, Dovzhenko filmed his first movies in Odesa: Vasyl the Reformer (1926, now lost), The Diplomatic Pouch (1927), and Zvenyhora (1927). The latter is considered one of the best Ukrainian films of the 20th century. Although the screenplay was originally written by Maik Yohansen and Yuriy Tiutiunnyk, a dissatisfied Dovzhenko made significant rewrites to it.

“Odesa caught cinemania,” wrote Mykola Bazhan about that time. “It was no surprise to see horsemen with epaulettes riding through the streets, firing shots into the air. It was the cinematic era of Odesa’s life. Before, it was a city of trade, a port…”

These lines come from Yanovskyi’s own diary. In a remarkable turn, the studio, which had previously released only two films a year, premiered an astonishing 26 films in 1926 alone! This impressive output represented 40% of the Soviet Union’s film production at the time. It’s also important to highlight that, amid ongoing ‘Ukrainianisation’ policies, all these films showcased a distinct Ukrainian folk character — a true cultural expansion!

However, as the ‘indigenisation’ policy rolled back and repressions intensified, along with the physical destruction of the intelligentsia, the film capital by the sea began to decline, and the centre of film production shifted to Kyiv.

Another vibrant chapter in the history of the Odesa Film Studio unfolded decades later with the work of director Kira Muratova, who began her filmmaking journey in the 1960s. Although her films faced bans for many years, they finally gained recognition in independent Ukraine for their technical innovation, philosophical depth, and sincerity. Muratova’s works received acclaim both at home and abroad, earning awards from prestigious institutions like the American Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences and the Berlin International Film Festival.

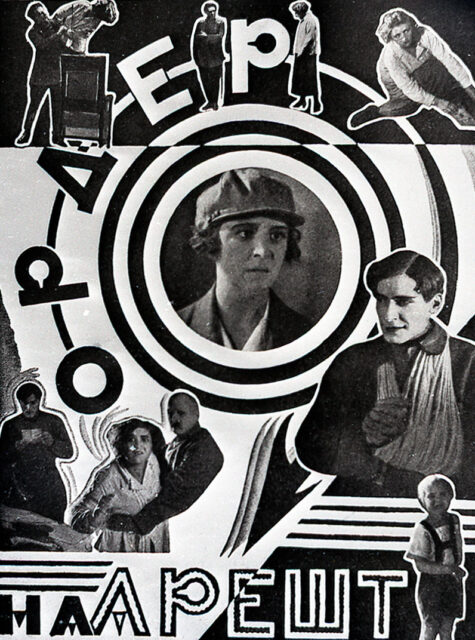

Movies to watch: Zvenyhora (1926, directed by Oleksandr Dovzhenko), Order for Arrest (1926, directed by Heorhiy Tasin, featuring a modern version with musical accompaniment by the band Vagonovozhati), and The Asthenic Syndrome (1989, directed by Kira Muratova).

Further reading: Yurii Yanovskyi’s Master of the Ship, a vivid portrait of Odesa’s film studio from within, where each character is inspired by one of his colleagues; and Yosyp Kozlenko’s Tangier, a fictional exploration of cinematic Odesa during that era.

Photo: ‘Order for Arrest’ film poster

Kyiv Film Factory: “The Ukrainian Hollywood on the Dnipro River”

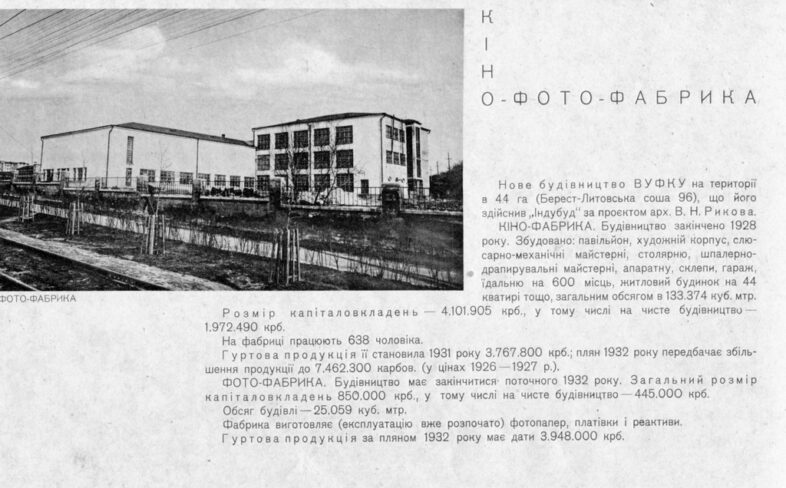

Amid the tremendous success of the Odesa Film Studio, a decision was made in 1926 to build another studio in Kyiv. This ambitious project—a 40-hectare film complex—was completed in record time, just one year. By 1928, what was reported as the largest film production facility in Europe opened its doors with the film Vanka and the Avenger (dir. A. Lundin). One of the standout features of the new studio was its 3,500-square-metre soundstage, spacious enough to accommodate several dozen films being shot at the same time, with enough room for cars, a train, and even an airplane to enter comfortably.

Photo: Construction of the Kyiv Film Factory

Despite the many historical upheavals, the film studio never fully stopped operating and has experienced several unique periods of growth, producing some of the greatest films in Ukrainian cinema. Leading the charge was Oleksandr Dovzhenko, who moved from Odesa to Kyiv after a few years. In recognition of his contributions, the studio has carried Dovzhenko’s name since 1957. Alongside this Ukrainian cinema maestro, the Kaufman brothers also worked here, one of whom became known as Dziga Vertov. It was at this studio that he created his iconic films Eleven, Man with a Movie Camera, and Enthusiasm: Symphony of the Donbas, all of which had a profound impact on the development of a unique cinematic language, much like the work of Ivan Kavaleridze, who also contributed to the studio’s legacy.

Avant-garde art was quickly banned and destroyed by Soviet authorities, leading to the studio’s being renamed as Soyuzkino. The next significant chapter for the company unfolded in the postwar era, especially during the 1960s, with the rise of ‘poetic cinema’. This unique artistic movement in Ukrainian cinema is celebrated for its distinct, “poetic” visual style and is primarily associated with Yurii Illienko, along with notable figures like Sergei Parajanov and Ivan Mykolaichuk. While the definition of the genre is somewhat narrow, only about twenty films— all produced at the Kyiv studio—are considered part of “poetic cinema.” Each of these films stands as a powerful and unique cinematic masterpiece of global significance. Unfortunately, this cinematic renaissance suffered a fate similar to that of the avant-garde; by the 1970s, films with their vibrant folkloric character were either banned or heavily restricted.

Photo: Page from ‘The Construction of Socialist Kyiv’ book, dedicated to the Kyiv film studio

The 1990s marked another intriguing yet relatively unexplored period for the studio, featuring cinematic gems that encapsulated the hopeful yet uncertain spirit of the final years of the USSR. This atmosphere is beautifully captured in the work of director Roman Balayan, particularly in his film Flights in Dreams and Reality, where the portrait of an era intertwines with the fate of a single individual.

With nearly a century of history behind it, the Dovzhenko Film Studio has produced over 1,200 films. The story of this studio and its production space continues today as an integral part of Ukrainian cinema in modern Ukraine.

Movies to watch: Man with a Movie Camera (1929, directed by Dziga Vertov), Earth (1930, directed by Oleksandr Dovzhenko), Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors (1964, directed by Sergei Parajanov), Flights in Dreams and Reality (1982, directed by Roman Balayan).

Further reading: VUFKU. Lost & Found (published by the Dovzhenko Centre)—a near-detective documentary account of the forgotten, lost, and rediscovered films of the 1920s.

Photo: Dziga Vertov (far left) on set during filming

Yalta Film Studio — cinema with an ethnic flair

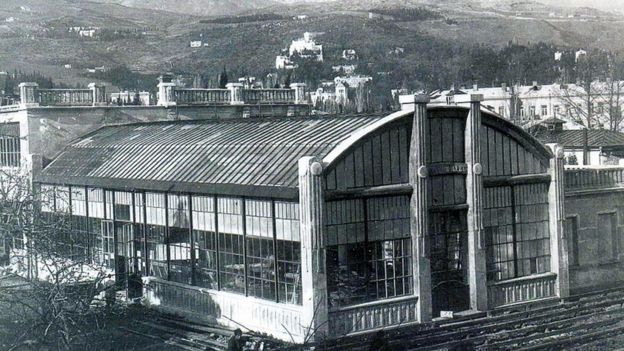

The story of Ukrainian cinema wouldn’t be complete without the Yalta Film Studio in Crimea. Established almost simultaneously with the Odesa studio, it was the first (and only) studio to focus on Crimean Tatar themes. While its history could have been longer, a sudden earthquake in 1927 caused significant damage and forced management to relocate most of the equipment to a new facility in Kyiv.

Yalta Film Studio. Photo: Stanislav Tsalyk

Despite its short lifespan, the studio produced around thirty films, with screenings held in Germany, the United Kingdom, France, and the Czech Republic. Its most renowned director was Volodymyr Hurdin. After the 1920s, the film factory continued to operate, though at a limited capacity. Unfortunately, the studio is currently experiencing its most tragic chapter. Since Russia’s occupation of Crimea in 2014, it has come under the control of the aggressor state.

Movies to watch: Ostap Bandura (1924, directed by Vladimir Gardin), Alim (1926, directed by Heorhiy Tasin).