Sisters and artists Alina and Karina Haieva have captured the hearts of Ukrainian and international audiences with their creative projects. By tapping into the traditional artistic skills of their ancestors, they infuse these age-old traditions with contemporary ideas and forms, breathing new life into their heritage. As the great-great-granddaughters of renowned artist Maria Prymachenko, they believe that talent is something you develop through hard work, not inheritance. They see heritage as a reminder of core values. We sat down with the Haieva sisters to talk about their childhood and early artistic achievements, the full-scale invasion, their move to Austria, their studies at the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts, their conscious decision to return to Ukraine, their meeting with a descendant of Ukraine’s last hetman, Rozumovsky, their participation in Paris Fashion Week, and the large-scale “Yaroslav and Ingegerd” project about the times of Kyivan Rus, as well as how art can shape global perceptions of Ukraine.

– What kind of environment did you grow up in? What was it like?

Alina: It was a mix of everything. We were born in the Mykolaiv region. Our mom is half-Lemko—our grandfather was displaced during Operation Vistula, and our grandmother’s family lost everything during Soviet times. On our dad’s side, he’s from the Kyiv region. His mother was related to the artist Maria Prymachenko, and his father was Roma. So we’ve got a bit of East and West, North and South in us. We were born in the village of Dobre in Mykolaiv, but we moved to Dnipro when we were three. That’s where we went to kindergarten, school, and university.

Dnipro played a major role in shaping who we are—it gave us a tough, almost unbreakable foundation. The city exudes an industrial spirit, as if steel flows through your veins. Yet, our roots remain deeply anchored in the South.

– You grew up in Dnipro. What was it like? Who did your parents interact with? Was it an utterly Russian-speaking city back then?

Karina: Dnipro was mostly Russian-speaking, but we were surrounded by a Ukrainian-speaking circle. It wasn’t until our teenage years that we noticed other social groups. Like most kids, by the time we were 8, we wanted to join clubs, and we ended up in an art studio, even though no one around us was into drawing or visual arts at the time.

Alina: Basically, we spent the school year in Dnipro, but every summer, we were in Mykolaiv, in the countryside, surrounded by the local dialect. At home, we spoke a mix, but in kindergarten, everyone spoke Russian—except for the Ukrainian songs we sang.

Karina: Which no one really understood.

Alina: Yeah, and at school, it was mostly Russian too, but like Karina said, we joined the art studio by second grade. We also grew up in a private house with a yard, so we weren’t really apartment-block kids. For us, it was always about the yard, the land, and the house.

Karina: The area we grew up in had an irregular layout, with individual plots. Our mother’s house was in Yekateryninska Slobidka, which used to have royal stables and the city’s only brick factory, built during Catherine the Great’s time. Dnipro, as you know, is famous for its red brick architecture because the bricks were mined and produced in Yekaterynoslav, the old name for the city, and most houses were built from them.

Alina: Yeah, they were top-quality bricks.

Karina: So, the landscape was completely unique—these “favelas,” little buildings, some made from clay, gave it a kind of romantic vibe. It wasn’t your typical city scene.

Alina: And it was right in the centre of Dnipro. We could walk to the academy in about half an hour, and if we rushed, we’d reach the Central Department Store (TsUM) in 20 minutes. So, it was a private sector right in the heart of the city.

Karina: A lot of Jewish quarters, too.

Alina: Yes, Jewish quarters really shaped that central part of the city. I think our sense of architecture was influenced by this. We weren’t confined to typical layouts. Our house was small, just 75 square meters, but it wasn’t a one-room khrushchyovka [a low-cost, concrete-panelled Soviet five-storied apartment – ed.]. It was built in 1935 and had two cellars and two entrances because it used to be split between two owners. Later, the second half was bought and merged.

Karina: The house sat on a plot of about 600 square meters. It felt like we were in the city but not at the same time. We had our own yard and an apple tree. And symbolically, we lived on Leontovych Street—of course, we know who he was. So, in a way, our mother, who moved from Dobre to Dnipro, brought with her the rural tradition of living in a house, not an apartment. That’s how we ended up in a house. It was wonderful.

Alina: Even though she got her education in Kyiv, met our father, got married, and somehow ended up in Dnipro, thanks to some distant relatives. The narrative of living in a house really runs through our whole lives.

Karina: A house in the middle of an industrial city—the contrast is still part of our lives today. So much of this makes sense when you look at it in context.

Karina Haieva on the workshop balcony. Photo credit: Kateryna Gladka.

– So, the journey to becoming an artist wasn’t a straightforward one. Given the fact that both of you chose this career, do you think you might have ended up doing something completely different?

Alina: Absolutely! You know how all kids love to draw? We did, too. The only difference was that I’m left-handed, which made things a bit interesting, but I never had to change that. Karina’s right-handed, so we made it work, sharing one box of paints between us.

Karina: And so many other things!

Alina: But when we were in the art studio, we didn’t really shine. There was no burst of talent or anything like that. Honestly, we were a bit behind.

Karina: Right? We were pretty average kids. Definitely not prodigies at 7, 8, or 9 years old.

Alina: Eventually, we even stopped going to the studio because we couldn’t afford it. But then, our instructor encouraged us to come back. What really set us apart was our determination and hard work.

Karina: We always did our homework and attended all the extra lessons they offered for free. By the time we turned 9, it started to pay off: our works were selected for an international exhibition at the Dnipro Art Museum. Out of ten pieces, six made the cut! It was a big deal for us back in 1996. For our studio, it was a major achievement. Then came the competitions, and Alina and I took turns winning.

Alina: For instance, Karina’s painting was showcased at the Ukrainian House before Alla Horska’s exhibition in 2001 (laughs). That’s when we first heard about Maria Prymachenko. We were at our grandmother’s, flipping through a photo album, and she casually said, “By the way, this is Maria Prymachenko, your great-grandmother’s cousin.” Just like it was no big deal! But we didn’t start painting because of her; by then, we already had our own accomplishments.

Karina: So, the topic of Maria Prymachenko wasn’t really central for us. The media often highlighted that family connection as if it was the key to our talent.

Alina: For us, it’s more about continuity. Even though no one in our immediate circle painted, it was still part of our family’s legacy. Ultimately, you need to nurture your own talent.

Karina Haieva in her workshop. Photo credit: Kateryna Gladka.

– I’d like to take you back to 2016, when the war in Ukraine was already underway, and you, Alina, became involved in the large-scale project “Ukraine Exists,” which was showcased in various cities across the U.S., including at the UN headquarters. Can you share your experience and how people responded to a Ukrainian artist?

Alina: I actually came up with the name for the exhibition to draw attention to Ukraine. Taras Topolia from the band “Antytila” invited me to participate, and I took on the role of art curator, bringing together the artists. We had around 25 artists, each contributing several pieces, which made the exhibition pretty hefty—about 2 tons! These were large works that formed part of a complex project, and the paintings were just one aspect of it. At the heart of the project was documentary material, including the film “Ukropy Donbasa” by Horovy and a few others. We were at the UN in January 2016.

The project served as an honest documentary about Donbas and Ukrainian art. We showcased what was happening in the region while also looking ahead and discussing how art could guide us toward a brighter future. There was an immersive video-audio installation featuring four plasma screens set against a map of Ukraine, surrounded by paintings from 15 artists nationwide. Our time at the UN was brief, as the project then moved to New Jersey, the Ukrainian Cultural Center, and later to Toronto, Chicago, and back. The whole process, including logistics, took nearly a year. The response at the UN was overwhelmingly positive. People approached us from all walks of life. I remember one woman saying, “You’re like a modern Michelangelo.” I replied, “Yes, I know” (laughs). The feedback was varied, which was exactly what we aimed for. For me, the idea of unity in diversity is crucial, and art should never be confined to specific canons.

But back then, no one really understood how long the war would last. We thought we were already behind the curve; it was 2016, and we felt like we’d missed the critical moment.

It was tough for me because I had to manage both the documentary aspect of the project and all the logistics for transporting the artwork, including navigating customs. Shipping 2 tons by plane was quite a challenge, especially since it was my first time handling something of that scale. I made a lot of new connections, but I also faced many hurdles. At that time, my daughter was only a year and a half old, and I spent a month in New York, which was incredibly hard for me.

In the end, I didn’t finish the catalogue, but it turned out beautifully. I even added two dots—yellow and blue—to the title “Ukraine Exists.” Later, I was surprised to see a similar design in an ad for Kyivstar because that was my idea. Overall, it was a fantastic experience but also exhausting.

Unfortunately, the Ukrainian Museum in New York backed out of our exhibition at the last minute, which created a huge problem. Suddenly, I had to relocate the entire exhibition of over 150 paintings, and I only had eight days to find a new venue. Thankfully, I managed to secure one, and a two-ton truck rolled into the UN to load everything up as we prepared to leave New York. It was snowing, and the city was shutting down, forcing me to trudge through knee-deep snow in my boots. On top of that, I had to deal with visa issues—an enormous source of stress.

To make matters even more surreal, the day we arrived in New York, David Bowie passed away. It felt like the whole city came to a standstill, with all eyes on that event.

At that time, while European institutions were organising similar exhibitions, “Ukraine Exists” really stood out. People had varying reactions to our message, but overall, the response was positive. It reinforced the idea that it’s not just about artistic representation; it’s also about the message we convey through our work.

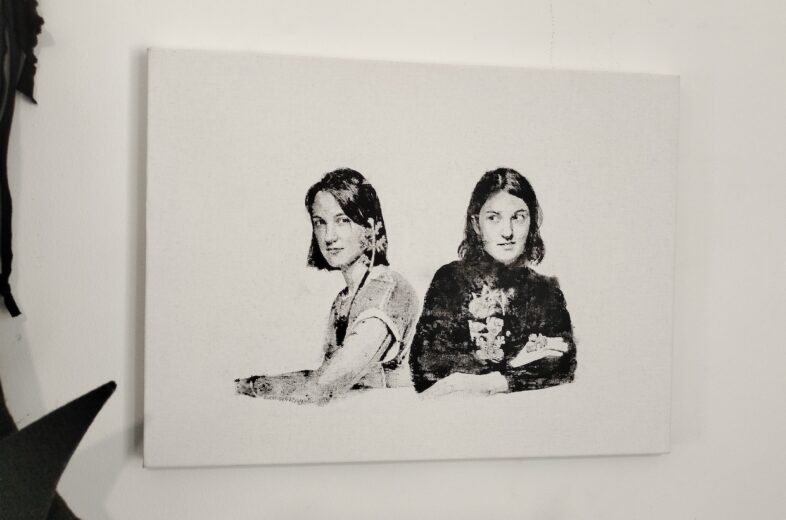

Sisters in the workshop. Photo: Kateryna Gladka.

– Did you feel at that time that this project could make an impact? Was it a form of people’s diplomacy?

Alina: Absolutely, that was our goal. We knew exactly what we were aiming for. It was also around the time when Dmytro Kuleba had just been appointed as the Minister of Foreign Affairs.

– But overall, was there already a decline in interest in Ukraine? The Revolution of Dignity had ended, and the war had been ongoing for a few years.

Alina: I felt like we were coming in late, like, “Oh, here we go again with Ukraine.” But people really responded to the art, especially the paintings. I believe it had a significant impact, demonstrating that Ukraine not only exists but that something deeper was happening—people were suffering, crying out, and being killed. The world might think, “Well, people are being killed in many places,” because that’s a daily reality for many. But art captured attention; it was vibrant, engaging, diverse, and modern, even featuring digital pieces. A lot of the artworks were sold, which shows that art is essential.

– Let’s go back to February 24th and the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. How did you experience that moment? Were you in any way prepared?

Karina: Honestly, we didn’t have an emergency bag ready. It all felt so distant as if it were happening somewhere on the horizon. But I remember thinking I wouldn’t go into a bomb shelter with the kids, so we decided to leave. My youngest was just five months old at the time. We packed up and headed to my mother’s in Austria. The journey through Ukraine took us three days, and it was an experience all on its own.

– Did you leave in the first days of the Russian invasion?

Karina: Yes, we hit the road on February 25th. Within 12 hours, we realised that men wouldn’t be allowed to cross the border anymore. My husband drove us to the border, and then we had to cross on foot. We had planned to drive across, but the queues were just insane.

So, at the last minute, we decided to leave the cars behind in Ukraine and walk over. Once we crossed, my mom picked us up. By March 1st, 2022, we were already in Austria at my mom’s place.

Alina: During those three days travelling across Ukraine, I felt a real sense of community. The weather was nice, and the military equipment and soldiers looked impressive. We only had to wait in line for fuel once. In the town of Haysin, some locals took us in for the night, and we stayed there with people from Kharkiv. The atmosphere felt different—almost “special.” We crossed the Slovakian border near Uzhhorod in just ten minutes, but then we ended up waiting five hours in a large red tent with other Ukrainians. We were surprised to see Roma and Hungarians from the other side of the border coming to collect Ukrainian humanitarian aid.

I was travelling from Kyiv with my daughter, Marusya. On February 23, I had a fantastic meeting and received a fresh preview copy of Antiquarian magazine, which was dedicated to 1918. While I was sitting with the editor, she suddenly exclaimed, “Oh God, can you imagine tanks rolling in?” I replied, “No, no way.” I hadn’t really prepared anything, but somehow I felt ready. The most important thing was that I had filled up the car the day before. The only thing I didn’t do was pick up my tattoos from the studio.

On February 24, I headed to my studio in Podil, crossing the bridge alone. There was hardly anyone around, just a metallic tension in the air. I collected my things and started to head back. Near a military unit, I saw our tanks already stationed. That was when we made the decision to leave.

The road to Zhytomyr was terrifying; it was completely jammed. Karina ended up driving in the opposite lane with her hazard lights on, but she managed to get there quickly—about eight hours, given the situation.

– So, your mom lives in Austria? That must have made leaving a bit easier.

Karina: Yes, it really helped. It’s nothing like what others faced, leaving without knowing where they were going. Our mom has been living near Vienna since 2018. She remarried, and they have a lovely family and a nice house.

Alina: I told my daughter that this was just the beginning of a vacation, and we were off to see her grandma. But even as we drove to Austria, we knew what lay ahead. We literally mapped out our plans in the car. We realised we would continue our work—promoting Ukrainian culture through visual art and design—but with even more energy, determination, and creativity.

Photo: Yuriy Stefaniak

– Did your older daughters ask where you were going?

Alina: They were fully aware of what was happening. They were preparing for a full-scale war at school, so my daughter was actually more informed than I was. She told me, “If it happens, you need to run to the bathroom.” That first night, something landed right next to us, blowing out the first floor of a building near our street, but we didn’t go to check it out—I just didn’t want to expose them to that kind of experience.

– How did things get organised in Austria? You got into the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna—how did that happen?

Alina: Well, to be precise, preparation takes time. Karina and I first visited Vienna as students in 2010. Then my mum got married, and in 2018, I attended an event about tattoos while visiting her. During my time in Vienna, I had numerous meetings, and many people suggested I meet Gregor Razumovsky, a direct descendant of the last Hetman, Kyrylo Rozumovsky. He is very pro-Ukrainian and strongly supports artists. However, at that time, I didn’t have much to show him. Still, I believed that when the moment was right, we would connect. So, when we arrived in Vienna in 2022, I immediately reached out to a friend and said, “What was it you wanted to arrange with Gregor? We’re ready now.”

In 2021, I created a large painting titled “Territory of Reality, a Groundless Country,” which explored the complexities of life in Ukraine. I completed it at the end of the year, and immediately felt a sense of sadness. As a tattoo artist, I had initially become intrigued by ornaments in that context. Our talented musician, Alina Krut, came to me for a tattoo, and I didn’t want to use just any design. I had received requests for intricate ornaments, which led me to delve into the world of 18th-century ornamentation and embroidery. I had begun sketching some ideas and sharing them on social media, but I hadn’t yet formed a cohesive narrative; I was simply captivated by these designs.

As we drove towards Austria, I realised I could base my project concept on this newfound fascination, having immersed myself in the theme for the past two months. It struck me that the Cossack elite, the last hetmans of Ukraine, and Gregor Razumovsky—the descendant of Ukraine’s last hetman—were all interconnected in this journey. We were moving towards this moment, and it was also moving towards us.

Photo: Kateryna Gladka.

– Did you meet Gregor Razumovsky?

Alina: We arrived in Vienna on March 1st, and by March 2nd, we had a meeting lined up with Gregor. By then, we had already developed our project and had a solid concept ready to present. During the meeting, we shared our ideas with him, and he was genuinely interested. We met with him again a week later, and that’s when we finalised the project. I painted Kyrylo Razumovsky and gifted it to Gregor, who appreciated our concept and promised to share it with others.

Shortly after, we received an invitation from the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts, saying, “Hey, we invite you to the Academy.” Two weeks later, we began a course led by Veronika Janečková, which lasted three months and culminated in an exhibition centred around collaboration. We were told that the professor was quite strict, but when we finally met her, we felt an instant connection—like she was our third sister.

We hadn’t even known about this academy before. It’s worth mentioning that this is the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts, the same institution where Hitler applied twice and was rejected, but they accepted us! (laughs) We hadn’t paid much attention to European education previously. Established in the 17th century, it’s one of the five oldest art academies in Europe, boasting an incredible collection that includes originals by artists like Bosch.

By that point, we had already created a website, and my painting “Territory of Reality” drew inspiration from Bosch. When we shared this with the academy, their attitude towards us shifted dramatically.

The staff expressed their gratitude, saying, “We’re sorry that the war has put you in this situation, but in reality, you’re our colleagues, not just students.” They were particularly impressed by Karina’s design work, our website, and the references to Bosch in our art.

They apologised, saying their students mostly showcased their work on Instagram, which couldn’t compare to what we were doing. After that, we became an example for everyone. The course had students from all over the world, including a student from Madagascar.

– Karina, you were also working on a clothing collection in Vienna, right?

Karina: Yes, that’s correct! While Alina was sharing the project concept with me from the front seat, I started refining it to give us a more comprehensive approach. Not long after, the name “And Flowers Will Grow on the Ashes” emerged. Everything came together perfectly: we had the right conditions, our ideas were aligned, and it turned out that the ex-wife of my mum’s husband had experience in sewing, so we had access to sewing machines.

We transformed a room filled with the necessary equipment and a cutting table into our workshop. We created a series of vests adorned with hand embroidery that showcased ornaments from the era of the Cossack elite. Once the exhibition at the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts opened, the project began to evolve into something more substantial. It eventually travelled to Ukraine, exhibiting in Lviv and Dnipro, and was featured twice in Venice.

Throughout our time in Austria, we dedicated ourselves to this project, continuously refining it. I feel that, at this point, it may have reached its conclusion, but it’s still set to go to Seoul before we move on to new ventures. We’ve learned a lot about what long-term work on a project truly means.

– Is it important for you to follow trends when creating collections? I mean not just the concept but also the format—like upcycling, which has become popular worldwide, from niche brands to the mass market?

Karina: You know, when we arrived, I realised that while there was a wealth of resources, there were very few people and almost no ideas. We had plenty of ideas and knew exactly how to bring them to life, so we started utilising that creative energy actively. I can’t wholly shield myself from trends, even though I consider myself a bit of an outsider. I’m drawn to deconstructivism—designers like Yamamoto, Kawakubo, and Margiela—who represent a niche culture with a unique style.

In the West, upcycling is more naturally integrated into the fashion landscape because, here in Ukraine, we don’t have a major issue with overconsumption. Instead, designers who focus on upcycling are more aligned with global trends. In Western markets, however, the challenge is to figure out what to do with the old as new ideas emerge. The waste disposal system is structured completely differently; in the West, you have to pay significantly to throw things away, whereas here, it’s often better to find a way to repurpose them.

I implemented upcycling in several pieces that were showcased at Paris Fashion Week in October 2023.

Alina Haieva working in her studio. Photo: Kateryna Gladka.

– Let’s return to the topic of printing. Did you bring any stamps with you from Ukraine?

Karina: They weren’t in our emergency suitcase; we didn’t even think about that when we left. However, after a series of meetings with Gregor Razumovsky, we began reaching out to contacts to help us integrate into the art community.

Surprisingly, we managed quite well, even though we didn’t speak German. We translated all our presentations into German, and if they were written, we also translated them into English. The children picked up the language very quickly in their surroundings.

The Ukrainian community in Vienna is quite large, with two Ukrainian schools. One of them is in a beautiful building and is affectionately referred to as the Ukrainian “Hogwarts.” It’s a Saturday school that actively hosts various events, fairs, and workshops on printing, and we even held our event there. They also have connections with other Ukrainian entrepreneurs, including those who run their own establishments.

There’s also a centre called “Barbareum” at St. Barbara’s Church, where various presentations are held. This venue is used for choir rehearsals and has welcomed many people from Ukraine. We’ve conducted printing workshops there multiple times.

Regarding the lack of stamps, we received an offer to hold a workshop, so we needed to find a solution. Friends in Vienna suggested printing them for us on a 3D printer. For them, this is quite common; they have one at home and use it to make all sorts of household items. I sent them the designs, and they created our first stamps in Austria, which we still use today. Later on, we decided to buy our own 3D printer.

– You participated in Paris Fashion Week. Can you tell us more about your journey there? How are participants selected?

Karina: First of all, it’s a truly global event. There’s a clear hierarchy, with haute couture at the top. Honestly, we can’t even dream of being part of that, let alone actually getting in. Haute couture is a title awarded to fashion houses based in Paris, and 90% of the pieces are made by hand. While working by hand is easier and more traditional for us, it’s still quite a challenge in that context.

At Paris Fashion Week, we participated not in the main shows but through the Flying Solo platform. This platform showcases clothing designers during fashion weeks around the world, featuring around 75 designers of clothing, shoes, and accessories.

Imagine our surprise when we arrived in Paris to find that the organisers were from the United States, along with girls from Kyiv. It really shows how connected Ukraine is on the global stage.

We often underestimate our own capabilities here. It’s only when we leave the country that we start to realise how professional we are and how present Ukraine is across various sectors.

The show isn’t just for show, unlike in Kyiv, for instance. We participated in Ukrainian Fashion Week only once, back in 2018. That event also served as a platform for young designers and involved a selection process.

In Paris, the application process is quite different. You submit your collection, along with descriptions and photos, and the review can take around six months—or even longer. At that point, the collection doesn’t have to be fully realised yet, but you do need at least sketches or concepts of what you intend to create. Once selected, you pay for your participation and bring everything with you; they provide the models. The entire show lasts about six minutes.

However, the true significance lies in the platform’s role in disseminating information. They select brands based on style and distribute catalogues to major global publications like Vogue and Elle. They also produce large promotional videos, so after the show, you receive a wealth of materials. It all makes perfect sense. Each designer has their own reasons for participating. In fact, a jacket from our collection was quickly snapped up by Ukrainians in Paris.

– What specific models did you present at Paris Fashion Week?

Karina: We showcased two models made from upcycled materials at the show. This time, I used a different approach than usual. There were eight looks in total, and each one was entirely distinct, serving as a preview of a larger collection that could be based on each look. This concept can be further expanded into broader ideas. For instance, an Asian male model wore a printed suit that suited him perfectly, even though the suit was unisex. Our printing was featured at Paris Fashion Week, along with a Scythian pectoral [golden pectoral found in the Scythian Tovsta Mohyla barrow in 1971 – ed.] designed as appliqués printed on velvet. We also presented a completely upcycled sweatshirt and a model entirely printed with Alina’s artwork. I exclusively use my sister’s prints in my clothing, which include both graphics and paintings. I really love painting, especially when we print it on fabric; it creates a truly unique story.

– Did you notice a shift in attitudes towards Ukrainians in France and Austria before and after the invasion?

Karina: Absolutely, people have finally begun to recognise us. For instance, the Academy displayed a large banner on its façade that read, “Solidarity with Ukraine.” This initiative came from both the teachers and students who were closely following the events. Even though Austria is a neutral country, the artistic communities and educational institutions have all stood with Ukraine, viewing it as a civilised stance. What Russia is doing is considered wrongful and uncivilised towards a civilised nation. This issue has become more pronounced, and it’s clear that people are now more informed about us and are treating us better.

Emigration is a new topic for many; these people didn’t leave in 2022 and generally hadn’t travelled before that. While there have been waves of Ukrainian migrant workers, this didn’t earn us much respect. It’s crucial to understand which segments of the population went there and how they were perceived because of this.

Stamps for block printing. Photo: Kateryna Gladka.

– Cheap labour…

Karina: Yes, and it was through those people that the overall attitude towards the country was formed. However, now Austria has experienced a different side of Ukrainians—immigrants who have moved here temporarily.

– Having education, language skills, and ideas…

Karina: These are highly skilled professionals in various fields. Austrians were somewhat surprised to learn that Ukraine is more than just a source of migrant workers.

We felt grateful to Austria, but the realisation of our potential in our work, which was difficult to achieve back home, was part of the reason we left. I believe those who stayed are thriving; they’re incredibly resilient. Ultimately, people choose what’s best for themselves, and that’s perfectly normal.

– At what point did you decide to return to Ukraine, and what was that feeling like?

Karina: First, I should note that during our time abroad—nearly two years—we returned to Ukraine more than twelve times, almost every month. It’s not far; Uzhhorod is only about 450 kilometres away. We weren’t the kind of people who just left and stayed away for a year. We maintained our connections and had work here. We were living not between two cities but between two countries. Production in Dnipro resumed within a month, allowing us to fulfil orders and send items to Austria for sale.

At the end of last year, in winter, we packed our three kids into the car and drove home through the fog. Visibility was nearly zero. People thought we were crazy for travelling in winter, suggesting we wait until spring. But looking back, I can confidently say it was the right decision, especially since winter was marked by a lack of blackouts. By spring, we had already secured significant projects, such as Brussels and the security forum with Arseniy Yatsenyuk. We wouldn’t have been able to achieve that if we had only returned in March. In March, we were already back in Brussels on a mission.

After two years, there comes a critical point where you must decide: either stay or leave. There’s a European narrative that doesn’t say, “Come on, maybe you should go home.” But when you choose to leave, they won’t stop you. This was true for us, both personally and globally, as our connection to Ukraine began to fade. We never aimed to integrate into Austrian society; we didn’t even study the language. I’m still unsure how we managed.

The conditions were harsh, but we weren’t in a camp. It baffled me that I couldn’t take my child to see their father without writing to the Ministry of Education for permission, which they wouldn’t grant for just a week. The travel took a day there and a day back, and these restrictions felt increasingly suffocating. As free-spirited individuals, we couldn’t tolerate that. So, we decided it was time to return. However, our mother lives in Austria, so this isn’t a permanent goodbye; it’s just temporary. The kids go there in the summer. We’ve made contacts and figured out how to work remotely. Even after we left, we had two projects in Vienna by October, all done remotely. This year, we took part in a significant project—a Nativity performance for the OSCE mission at Christmas. We sent 19 costumes, participated in the event, and then returned. So, everything is possible, but living there isn’t our story.

– Finally, could you share a bit about the project “Yaroslav and Ingherd: Life Story—Love Story,” which you presented at this year’s Bouquet Kyiv Stage art festival in St. Sophia of Kyiv?

Karina: One aspect of the festival was our master class on block printing, which we’ve been offering for the second year in a row. The other project is more expansive and has just begun; I’m confident it will continue to develop and travel to other countries. “Yaroslav and Ingigerda” is rooted in the story of Yaroslav the Wise and his love for his second wife, the Swedish princess Ingigerda. This period marked the flourishing of Kyivan Rus, and it’s essential to highlight it from various perspectives. We need to bring attention to this significant era.

The project has been underway for less than a year, initially intended for a presentation in Sweden, but everything kept getting postponed. Ultimately, we premiered it at the festival in Kyiv this August. I truly believe it was meant to be; we couldn’t have presented it anywhere else but at the sanctuary where they are buried.

Karina Haieva leading a block printing masterclass. Photo: Bouquet Kyiv Stage.

Alina and I dove into what could almost be called a scientific endeavour. We conducted in-depth research, embarked on a detailed tour with a researcher from the St. Sophia of Kyiv Museum, and devoured numerous books. We even approached all the staff members to gather information (laughs). We consulted with researchers and writers, including the Kapranov brothers, who are working on a series about Ingigerda. I truly hope the project will come to fruition, especially after the unexpected passing of Dmytro Kapranov in April. Our goal was to dig deeper, understand the dynamics among these figures, and explore who influenced whom.

The project, which premiered at the Bouquet Kyiv Stage festival, features an animated film complemented by a live performance from Dmytro Radzetskyi. Actress Kateryna Kisten portrayed Ingigerda, donning an upcycled dress and reading a fictional letter that captures her voice, telling her story in her own words. We processed a wealth of information, resulting in a film that is melancholic and contemplative, rich with symbolism and metaphors about the lives of Yaroslav and Ingigerda. The premiere also showcased an exhibition of Alina’s graphic works, which inspired the film.

The team behind the project “Yaroslav and Ingigerda.” Photo: Bouquet Kyiv Stage.

– On a side note, what’s the longest time you and your sister have been apart?

Karina: We’re not always together (laughs). Before the full-scale invasion, we lived in different cities, so we saw each other regularly, but we never went long without being in touch. We were always connected by phone.

I think the real challenge of being twins is dealing with separation. We know how to be together, but not so much how to be apart. That process of becoming separate is the main challenge of life, in my opinion. If you navigate it successfully, you won’t lose that connection; instead, you’ll each gain something personal that belongs to you, enriching one another in the process.