Like many Ukrainians, the theatre world is trying to balance the demands of war and everyday life. For those deeply involved, a typical day might look like this: after a night of relentless Russian shelling, people start their morning by donating to the Ukrainian army or local volunteers, spend the day talking about the latest news like seasoned political experts, and then try to unwind in the evening.

This emotional rollercoaster is tough on everyone, but theatres, which depend on their audiences, are finding ways to adapt. That’s why we’re seeing more entertainment-focused shows that tackle serious issues but in a way that’s easier to digest. On the other hand, plays that deal directly with the harsh realities of the war are mostly being performed in smaller venues for those still ready to face the rawness of the Russo-Ukrainian war. Even with these commercial challenges, playwrights are sticking to military themes. The Playwrights’ Theater in Kyiv is a great example. Their lineup, which already includes several war-themed productions from last year, now features a new play by Alona Al Yusef called “Can You Hear Me..?,” based on Anna Halas’s “Chronicles of an Evacuated Body and a Lost Soul.” This touching play about loss, written about two years ago, might not attract a huge crowd, but that doesn’t mean people aren’t interested. It’s more about taking a thoughtful look at the early days of the full-scale invasion.

Irony serves as a powerful defence mechanism in theatre alongside detachment. This is clearly illustrated by Oksana Hrytsenko’s tragicomic play Milkweed, written in 2022 and making waves in 2024 across various Ukrainian cities. The play, which humorously explores the early months of the Kherson region’s occupation and the use of folk medicine for both physical and spiritual healing, has been staged almost simultaneously by the Youth Theater in Odesa (directed by Yevhen Reznichenko) and the Theater on Podil in Kyiv (directed by Ihor Matiiv).

Another production of Milkweed is set to debut in Chernihiv under the direction of Andriy Bakirov, and it’s likely that this ‘healing plant’ will also take root in Vinnytsia or Zhytomyr. Beyond depicting the grim realities of war, Hrytsenko’s play charmingly portrays the interactions and conflicts among three generations, striking a chord with audiences. While it may lack the male figures of the Kaidash Family, the play unmistakably presents the archetypes of Ukrainian women.

The Entertaining Content

Despite its dramatic events and sombre ending, the work of Ivan Nechuy-Levytsky—a renowned Ukrainian writer of the late 19th and early 20th century—has long been a staple of Ukrainian theatre’s entertainment repertoire. His novella, while reflecting serious themes, has been adapted numerous times and remains a popular choice for the stage. Ivano-Frankivsk, for instance, now features its own standout production of The Kaidash Family, with Irma Vitovska as the unforgettable character of Marusia Kaidashykha and Oleksiy Hnatkovskyi as the novel’s noble Omelko Kaidash, all brought to life in Rostyslav Derzhypilsky’s rendition. Similarly, the Chernivtsi Theatre of Olha Kobylianska presented its own version at the end of the season, directed by Liudmyla Skrypka. Additionally, after the modern take on Nechuy-Levytsky’s novel, Kaidash 2.0, by Natalia Vorozhbyt, Maksym Holenko, the artistic director of the Maria Zankovetska Theater, is preparing to bring Lviv an authentic, unaltered rendition of Nechuy-Levytsky’s work.

Nechuy-Levytsky, celebrated for his comedic prowess and for initiating the beloved story of the two hares—a play that remains a classic of Ukrainian theatre—represents a cherished tradition. However, there is a growing demand for entertainment that embraces both local and international humour. This need was prominently addressed in the spring of 2024 with the major premieres of Chicago and On the Mermaid’s Easter at the National Operetta.

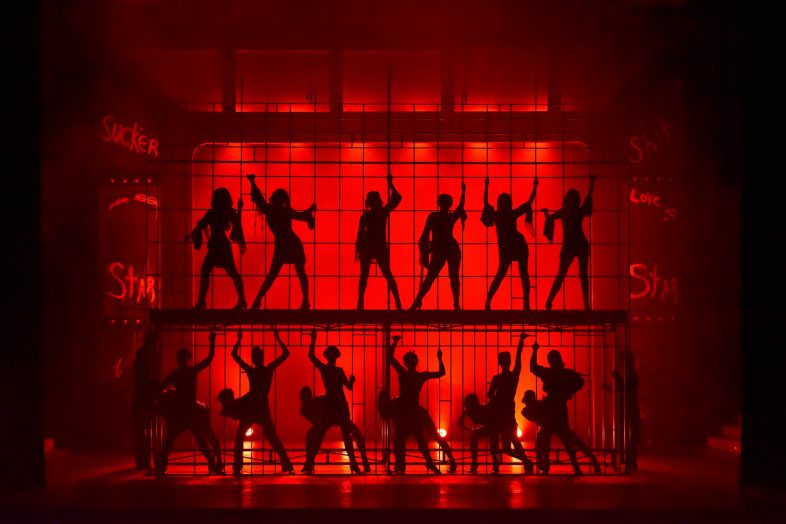

The Kyiv theatre has been meticulously preparing to stage John Kander’s Broadway hit Chicago for several years, a musical whose fame has only grown with its film adaptation. The extensive preparation went beyond merely securing licensing rights, developing an original concept, and crafting sets and costumes. The core reason for the lengthy process was Bohdan Strutynskyi’s deep understanding of musical theatre. Drawing from his rich experience, he knew that the success of this genre hinges on the flawless synchronisation of every element. Strutynskyi aimed to achieve a level of precision among actors and technical staff that meets the genre’s high standards.

To reach this goal, Strutynskyi departed from the typical Ukrainian stage approach, where soloists often overshadow the ensemble. Instead, his production functions like a meticulously crafted clock, with lead performers (three actors per role) serving as the hands that ensure the show’s flawless execution.

Audiences are unlikely to be fazed by this century-old American crime drama. Instead, they will likely be captivated by the show’s glamorous allure, charm, and vibrant kitsch—a heady mix of luxury, passion, and sensuality. This intoxicating blend might well sweep viewers off their feet, though such theatrical enchantment wasn’t the original aim of Chicago’s creators. Ironically, this sort of theatrical hypnosis was precisely what Mykola Leontovych envisioned for his lyrically melancholic piece On the Mermaid’s Easter.

The Intellectually Entertaining Content

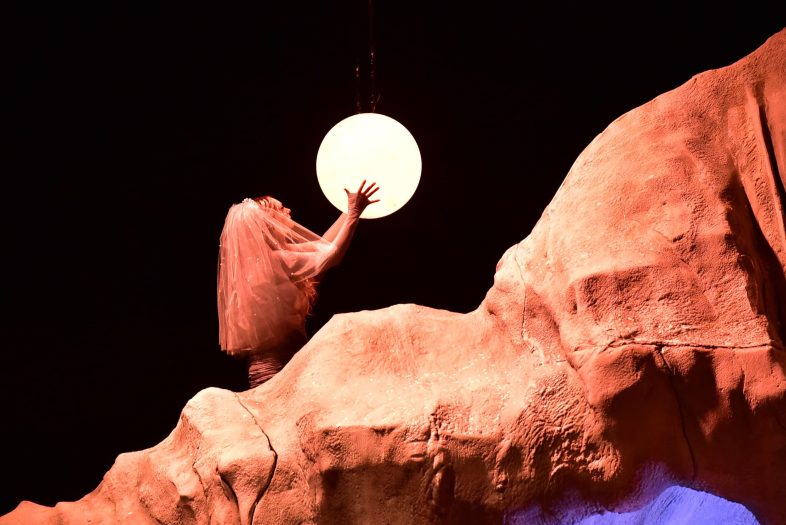

This mini-opera, On the Mermaid’s Easter, or more accurately, an etude about mermaids and a Cossack, was first presented at the National Operetta by Ivan Uryvskyi. Collaborating with artist Tetyana Ovsiichuk, Uryvskyi stripped the romantic tale of its sentimentality, setting it in a contemporary Antarctica where mermaids, not penguins, rule. These mermaids, with indifferent and disdainful glances, watch as plastic waste washes up on their shores—one of the planet’s last relatively pristine spots—where a drowning man in a wetsuit, representing the Cossack, struggles.

The on-stage spectacle is provocative and parodic, brimming with scepticism toward humanity’s wastefulness and consumerism, which are ravaging the world’s natural beauty. The characters—a troupe of mermaids doubling as models in neon swimsuits, the Cossack diver who might be an IT specialist on vacation, and pallid tourists keen to see the glacier up close—offer a sharply unflattering collective portrait of humanity.

It’s clear that the cartoonish sarcasm is apt for the contemporary context, but it also spills over into Leontovych’s mini-opera, which, unfortunately, doesn’t hold up perfectly. Currently, On Mermaid’s Easter seems too delicate to survive the reshaping of its plot, with its mystical elegance completely dissolving into the pop-symphonic style of Leontovych’s music.

In contrast, globally recognised masterpieces, which have been subjected to numerous stage adaptations over the past fifty years, prove much more resilient. Take Friedrich Schiller’s Mary Stuart, directed by Ivan Uryvskyi at the National Ivan Franko Theater. This production isn’t a historical exploration of 16th-century queens of England and Scotland but a commentary on today’s queens of showbiz, fashion, and ephemeral video content. It reflects the world of entertainment and the constant flood of trivial information. In response to the vision of director Ivan Uryvskyi, set designer Petro Bohomazov, and costume designer Tetiana Ovsiichuk, actors from the Franko Theatre—Vitaliy Azhnov, Akmal Gurezov, Tetiana Mikhina, Anzhelika Savchenko, Ivan Sharan, and others—delivered such a masterful critique of this world of pretence that some audience members took it at face value, rather than recognising it as satire.

Both the performers and the director, who occasionally contribute to the production of cinematic beauty themselves, demonstrate a deep understanding of the complexities and dependencies of the life they are satirising. The convincing portrayal in this stylish production, which is woven from Schiller’s text, evokes genuine sympathy first for Elizabeth, then for Mary. However, this fleeting empathy is quickly dispelled by cynical comments and the brazen antics of an additional character, Someone (Mykhailo Kukuiuk/Ivan Sharan), signalling that the creators of the performance clearly had no intention of indulging the audience’s emotions.

Using theatre to reveal the power dynamics within the social hierarchy is far from novel. Molière’s Tartuffe, written in 1664, was precisely for this purpose. In early 2024, Dmytro Bohomazov directed this play at the National Theatre, named after Ivan Franko. Unlike his previous works, where he engaged deeply with the text, debated interpretations, or infused his own ideas, Bohomazov chose to present Tartuffe in its original form, adding nothing new. By updating the setting to contemporary times, he infused the production with a caricatured, masquerade-like frenzy reminiscent of the Louis XIV era. However, instead of exotic Africans, the geometric greenery of Versailles is now home to King Kong. Orgon’s household resembles that of a mid-level oligarch, while the affectedly cautious Tartuffe (Andriy Saminin) and Orgon’s pragmatic brother-in-law (Mykhailo Kukuiuk) echo figures from today’s political circles.

The Intellectual Content

The candid critique embedded in comedies—since, in any era, including wartime, there will always be charlatans and manipulators exploiting others’ suffering—makes Molière seem, at first glance, more immediately relevant than Shakespeare. Shakespeare’s works, with their intricate plots and layered meanings, demand constant decoding. Interpreters must navigate a maze of hidden messages and complex intrigues to distil a singular, comprehensible message for the audience. The formidable challenge of this interpretive task was underscored by Ukraine’s inaugural Shakespeare Festival, an idea first ignited by the Donetsk Ukrainian Music and Drama Theatre nearly two decades ago and finally brought to life in June 2024 in Ivano-Frankivsk.

The festival drew a diverse crowd of Shakespearean experts and translators from Europe and the USA, critics, journalists, theatre managers, and, of course, a slate of performances. The anticipated highlights of the program were two recent Ukrainian premieres: The Tempest by the Lviv Theatre of Maria Zankovetska, directed by Oksana Dmytriieva and featuring Oleg Stefan as Prospero, and Othello, directed by David Petrosyan at the Lesya Ukrainka Theater in Kyiv.

The success of Dmitriieva’s intimate production, created for the small stage of Strykh, has already been affirmed by its invitation to the renowned Shakespeare Festival in Gdańsk. On the other hand, Petrosyan’s Othello, featuring invited actors from the former Kyiv’s Russian Drama Theatre—Oleksandr Yatsentyuk (Othello), Alexander Formanchuk (Iago), and Olga Goldis (Desdemona)—despite its sustained success with Kyiv audiences, still needs to establish its place in Shakespearean history. Nevertheless, this atmospheric production, where the audience encounters many attractions, undoubtedly possesses significant potential.

The production enchants with its poetic sails and costumes by Danyila Kolot, which gracefully envelop the performers’ bodies. The dynamic staging channels the performance’s energy, captivating the audience and compelling them to follow every movement and listen intently to each word and acoustic nuance. The central character is depicted as a noble warrior whose formidable combat skills fail to shield him from the web of intrigue and gossip. From the outset to the tragic finale, Othello is seen honing his steel sabre, believing that his martial prowess will ensure his survival in the civilian realm. Yet, in the final scene, the Venetian nobles display a cold indifference to the demise of the legendary warrior, their focus solely on securing a new protector for their interests.

Being a Legend

Despite the challenges faced in David Petrosyan’s production, Oleksandr Yatsentyuk, whose stage experience is evidently limited, delivers a compelling portrayal of Othello. Visually reminiscent of a Cossack, Yatsentyuk’s performance elevates the character to a legendary status—one that resonates within the pantheon where Ukrainian theatre venerates its icons. Recently, there has been a noticeable shift in the search for stage-worthy lives, as the well-worn themes of “old songs about the main things” are set aside. Over the past few years, this pantheon has grown, with the Ukrainian stage offering new legends.

Photo: Ruslan Lytvyn

Among these are notable adaptations, such as the novellas of Mykhailo Kotsiubynsky. These works appeared almost simultaneously in Kyiv: The Stranger, directed by Volodymyr Kudlinsky, at the Theatre on Podil, and Intermezzo, directed by Veronika Litkevych, at the National Theater of Ivan Franko. Additionally, the Odesa Theater of Vasyl Vasylko revived the play by the visionary Anna Yablonska, who tragically died in a terrorist attack at Moscow airport. The production of The Carrier, directed by Oleksandr Samusenko, brought her poignant work back to the stage.

Naturally, the most illustrious legendary status has been attained by the tragic figure of composer Volodymyr Ivasiuk, who has been commemorated with three distinct productions in Zaporizhzhia, Rivne, and Lviv. Among these, the musical Chervona Ruta, presented by the Lviv Theater named after Maria Zankovetska and starring the acclaimed actor Mark Drobot, stands out as a likely legend in its own right. This musical, which celebrates singing Ukraine, its patriots, and its potential traitors, is brought to life by director Maksym Holenko’s sentimental touch and set designer Yulia Zaulychna’s expressive, textured creations. Their collaboration weaves a tapestry of genuine emotion, creating a rare and powerful theatrical experience. Such moments are exceptional and can either emerge organically from the ground, as with Chervona Ruta or be inspired from above, as seen in Elegy of Wartime.

Photo: Ruslan Lytvyn

The title of the new mini-ballet by the internationally acclaimed choreographer Oleksiy Ratmansky, set to music by the equally esteemed Valentin Silvestrov, was unveiled at the close of the 2023–2024 theatre season at the National Opera of Ukraine. Elegy of Wartime marks a kind of jubilee, as it is the first time Ratmansky’s choreographic work has been presented on this stage in thirty years. Since the late 1990s, Ratmansky has been staging ballets exclusively abroad, having not been invited to perform in his hometown, where he spent his childhood and began his artistic journey.

Yet, this “citizen of the world” revealed his deep connection to Ukraine’s pain and resilience with remarkable artistry. The ballet Elegy of Wartime, suffused with both tenderness and sorrow, masterfully bridges the intense emotional and psychological states experienced during the war. Classical pointe duets give way to folk dance movements from male and female ensembles; Sylvestrov’s gentle chords transition to authentic folk melodies; and abstract projections by Matviy Weissberg are contrasted with life-affirming artworks by Maria Prymachenko. The pristine ceremonial costumes of Chopiniana (designed by Moritz Junge) are transformed into skirts of charred brown with streaks of yellow and blue, seamlessly integrating disparate artistic techniques into a cohesive portrayal of a wounded nation brimming with potential.

With its straightforward yet sophisticated artistic language, choreographer Oleksiy Ratmansky and his creative team eloquently depict the emotional extremes we navigate. Though it may seem clichéd to say that wartime leaves us breathless with fear and hearts frozen with hope, this duality is an everyday reality, and Elegy of Wartime captures precisely this truth.