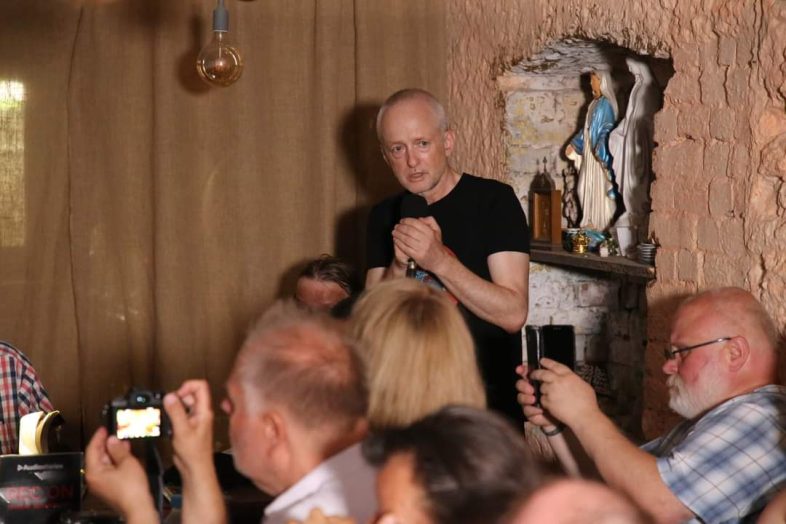

During Schulzfest, a festival celebrating the Jewish writer and artist Bruno Schulz in his hometown of Drohobych, one man stood out for his constant notetaking. Paweł Próchniak, a literary anthropologist, critic, professor at the Institute of Polish Philology at the Pedagogical University of Kraków, member of the Polish PEN Club’s Board Presidium, and program officer of the Zbigniew Herbert Foundation, was rarely seen without his small notebook. As a co-organizer and curator of the “Poems in Shelters” section, his detailed, metaphor-rich notes became the foundation for his insightful commentaries, which were worthy of being published as a collection.

This interview evokes the dreamlike world of Bruno Schulz. Picture Truskavets: a late evening in a small cafe, lights going out, a generator humming, faces lit by phone screens, and an intimate conversation. Yet, our discussion was grounded in the realities of life in Ukraine today. We explored the unique power of poetry, debated Ukraine’s pursuit of its missed past, and pondered why reading poems in shelters has become more than just appreciating texts.

– Can you recall your first encounter with Schulz?

– Yes, I do remember that. It was in high school, at the lyceum, and it was a very strange experience. I didn’t know what to make of it. At that time, I believed literature should speak directly about important things. Now, I no longer think that a direct and literal approach is the best solution. But back then, I was young, combative, and thought that way. My first reading of Bruno Schulz felt strange, almost narcotic—I barely understood anything. It was one of his stories, one of the few school readings I tackled before the class discussion. I had a rule to only read a book after it had been discussed in class. If it intrigued me, then I’d read it. Usually, it didn’t, but Schulz captivated me. Yes, that was a long time ago. Later, during my university years, I attended lectures by Professor Władysław Panas. He was writing a book about Schulz and Kabbalah at the time. This book, “The Book of Splendor,” was published alongside his second book, “Bruno the Messiah.” The lectures he gave were related to these books. They weren’t out yet, but I observed their creation process and listened, which was fascinating. This was largely due to Schulz, of course, but also because of Professor Panas, who was an intriguing personality.

– Throughout cultural history, we’ve seen numerous battles for memory, such as the conflict over Kafka’s legacy. How should we discuss Kafka in the digital age? Who holds his documents and the originals of his works? These are all different narratives about him. What is happening with Bruno Schulz’s collective memory? Here at Schulzfest in Drohobych, the Polish, Ukrainian, and Jewish perspectives converge to discuss something shared.

– This is a very interesting question, and it seems particularly important when discussing artists from borderlands. Schulz embodies these boundaries—you mentioned the Polish, Ukrainian, and Jewish aspects, but we could also include the Austro-Hungarian influence, among others. Schulz stands at the centre of these intersections. This raises the question: Whose Schulz is he? Is he Jewish, Polish, Ukrainian, or Austro-Hungarian? Disputes can arise if someone tries to appropriate Schulz’s work or any artist’s work to create a myth or use it for a particular purpose. It’s crucial to handle this carefully. Appropriating cultural works means using them for something, which is where caution is needed. This is the mystery of Schulz. Today, it often seems that art exists for a purpose, has a price, and can be bought. But in reality, true art is invaluable and cannot be bought. These priceless things, like love, cannot be commodified. Children, for instance, exist to be loved. Thinking that something can be appropriated, priced, and exchanged for money or social or political capital is a kind of crime against art, against something completely defenceless.

If we wish to honor Schulz with good intentions, we cannot do so solely from the standpoint of national identity. To truly remember Schulz, we must set aside these questions of nationality, social group, territory, and so forth. These categories do not pertain to art. While every literature exists in a specific language and is immersed in a particular time with its social, historical, and political context, these are merely incidental values—external factors. The essence of art lies elsewhere. Its true nature is in its disinterestedness and pricelessness. Art has no purpose; it simply exists as an invaluable entity.

– So, is it our personal perception that truly matters?

– Yes, a perspective is only honest when it is personally mine—not as a Pole or yours as a Ukrainian, but yours as Kateryna. Such a personal view is honest because, in reality, it’s the only one we have. Viewing Schulz strictly as a Pole would be dishonest. In this sense, if we look honestly, the memory of Schulz is shared and collective because it encompasses your memory, my memory, and the memories of others. We communicate more or less effectively, despite misunderstandings, not on a general national or purely cultural level, but through our shared journey toward the work of art, the artist’s vision, and imagination.

There is a more important aspect of this shared memory. Every work of art, especially poetry, often even a single metaphor or poem, creates a world that invites us in. This applies to a book and the artist’s entire body of work. We can enter this world: I, you, and others. Since this world is crafted by the artist’s vision, our memory, our thinking about it, and our participation in this vision become collective. The world invites us in, creating a shared experience.

There are two sides to this. The first is the particular, partisan, national perspective, which seeks to appropriate the work and use it for something, which is a crime. The second is the creation of a world we are invited into, where we are equal participants and guests. In this sense, it is our common world.

– Let’s discuss the part you curated at the Schulz Festival in Drohobych—the “Poems in Shelters.” How has it evolved from the initial idea you and organizer Vira Manyok conceived to its practical implementation now that the festival has concluded? What was unexpected, surprising, or perhaps just emerged along the way?

What surprised me the most was how well everything came together. I had faith in the concept—the idea of presenting poems in shelters and providing commentary felt essential and meaningful. I’ve been involved in similar projects for a long time, and my experience has taught me that things often go awry. What seems like a brilliant idea at first can sometimes fall short. However, I’ve learned that when a concept is simple, clear, and yet profound, it tends to succeed. It needs to be straightforward but not superficial, revealing some depth.

Finding a foundation in something natural and authentic is key. It’s about capturing an important phrase or thought, something that resonates deeply and can be shared. For instance, reading one’s own poem—while seemingly simple—carries a sense of reverence, like a ritual. In our current world, fraught with threats and challenges, this simplicity becomes even more significant.

During our readings in the shelters, we talked about how the linden trees once bloomed in July but now do so earlier due to climate change—a metaphor for the bombs falling on our world. In a world where threats are both literal and metaphorical, it’s crucial to focus on what truly matters and protect it. I didn’t expect that our series of eight meetings in shelters would coalesce into something so complete. Initially, it was just a collection of strong individual threads—one poem, one commentary at a time. But as we progressed, echoes and repetitions wove together to create a rich tapestry. I worried that time would be too short, our differences too great, and the bilingual nature of the project too complex. Yet, despite the heat and challenges, it all came together in a way that exceeded my expectations.

– Indeed, there was a sense of the sacred intertwined with a profound testament to life’s raw immediacy.

– It could have easily failed, so I was genuinely surprised by how well it turned out. I knew it was important, but I wasn’t entirely prepared for what I’m about to say. I added my own threads, comments, and reflections. Before events like the Schulz Festival, I usually prepare meticulously, knowing that day-to-day adjustments won’t be possible. I had written texts for the festival’s opening, for the conversation with Ryszard Krynicki, and for the introduction of the poems in the shelters. I expected these elements to follow their own course, guided by others. Yet, as the poems were read and discussed, they resonated with me more profoundly than I anticipated. I felt a strong need to provide additional summaries and commentary, which naturally led me to engage more deeply.

– Yes, your comments indeed set the tone and directed the spotlight. I saw you taking notes, observing details, and watching the poets over these days.

– Yes, I was indeed surprised by how well things turned out. Each time, I had the opportunity to introduce the readings, offer commentary, and then summarise. The final sessions were particularly striking because they included a soldier from the front lines and children from shelters across Ukraine, showing life unfolding before our eyes. I hadn’t planned to approach it this way; my initial plan was simply to prepare texts for the festival’s opening, for the conversation with Ryszard Krynicki, and for the poems in the shelters. I expected the readings would take their own course, with others providing commentary. But as the poems were read and discussed, I found myself deeply moved and felt a strong need to respond. I talked about how sometimes simply reading a poem isn’t enough, and that a response—whether writing or some other form—can be necessary. The resonance of the poems and the conversations was so profound that it surprised me, perhaps even more than the initial unexpected success. It all came together into a cohesive and impactful experience.

– Why does poetry often feel more powerful than prose during wartime? It might be a matter of perspective, but poetry seems to capture the essence of such times with greater precision and impact. Do you think this has something to do with the nature of war?

You’re right—poetry often seems easier, more precise, and somehow better, especially during intense experiences like war. But this isn’t just about conflict; it applies to other profound moments, such as illness, death, or love. Why do we turn to poetry in these times?

Perhaps it’s because language offers us two main ways to respond: through storytelling or metaphor. In crises, when there’s little time for elaborate narratives, metaphor steps in, and poetry becomes our go-to form. Poetry also has a magical quality—rhythm, melody, incantation, and a sense of prayerfulness, though not necessarily religious. We are drawn to respond with poetry when something deeply moves us.

Consider how children first react to the world—either with crying, which is a form of lamentation or with murmuring, a kind of early chant. These responses, both cry and song, are the roots of poetry. Poetry often blends these elements, capturing both the sorrow and the beauty in its verses.

I believe poetry resonates more deeply with human experience. This isn’t to undermine the value of storytelling, which is undoubtedly important and necessary, but poetry touches something more primal. It aligns closely with our hearts, souls, and bodies.

Poetry captures the rhythms we feel but often don’t consciously notice—like the beat of our heart or the flow of our blood. In absolute silence, such as in an acoustic chamber with all external sounds removed, you can hear your heartbeat and the sound of blood flowing. These internal rhythms are mirrored in poetry. Stories, on the other hand, tend to be more diffuse and often address others. Poetry, however, is frequently a direct conversation with oneself. Perhaps this is why poetry emerges so powerfully in times of crisis when the world is falling apart or burning. Descartes, despite his rationalist outlook, famously turned to poetry as he faced death, sensing that poetry captures something profound about our human condition in the face of life’s ultimate challenges.

– Ukrainian culture has long struggled with invisibility, even requiring prominent figures like Serhiy Zhadan, Oksana Zabuzhko or Yurii Andrukhovych to constantly “put Ukraine on the map” and explain its significance. While we are now more visible, there are still significant gaps—like missing translations, erased artists, and lost histories. Should we focus on addressing these historical gaps and catching up with the past, or should we concentrate on strengthening our present cultural presence and leaving the past behind?

– I prefer the latter. That is focusing on our local culture and tradition, engaging deeply with our language. However, I believe it’s essential not to limit this to the contemporary moment alone, as that could be overly reductive. To me, the idea of modernity is somewhat illusory. What we truly have are the memories of the past and the hopes and dreams for the future. The present is like the edge of a knife—sharp and precarious. We can’t dwell there for long; it’s a space that cuts and destroys. Instead, we need to draw from the depth of our past and gaze far into the future. Remembering and dreaming are crucial. Dreams are a form of hope, and hope is a form of dreaming.

The past, in particular, holds significant value for me. While our dreams and hopes are undeniably valuable, their true worth often becomes apparent only in retrospect. Hope is very much alive in us, and dreams are vivid and vital. Without them, we couldn’t live fully. But memory, too, is indispensable. This is vividly evident in language, which is why poetry is so crucial. Poetry preserves the essence of words, connecting them to their historical roots. Each word carries a legacy from the past, stretching back hundreds or even thousands of years. When I use a word like “is,” it reverberates with historical significance dating back to Proto-Indo-European times.

Poetry, therefore, is not just a reflection of the present but a bridge to the past. Language, as Steinberg insightfully points out, is a remarkable construct. The invention of the grammatical future tense, for instance, allows us to speak about things that do not yet exist—an abstraction that we have created. Poetry often functions as a dream, a form of hope, and in this way, it represents both the past and a future that is yet to come.

– So, it’s a blend of memory and envisioning the future?

Absolutely. It’s essential to build on what we have—our shared memories and hopes for the future—without worrying too much about whether someone in another country or language will fully grasp it. The real value of culture isn’t in its ability to be exported or showcased at international festivals. It’s found in the connections and experiences we share right here, like at the Schulz Festival. What really matters is the sense of community that brought us together. That’s the true worth of culture. If something is genuinely valuable, it will naturally attract interest from others.

There’s also a special case for smaller, endangered cultures. For instance, some small Pacific islands are facing extinction, with limited resources left. One such island had a small economy based on coconut palms and postage stamps. While the coconut palms are no longer viable, the postage stamps have found a place among collectors worldwide, preserving a piece of that culture. For these small, vulnerable cultures, sharing and preserving their unique aspects can be crucial for survival.

– Or consider Tibet, which had to share its culture with the West as a way to preserve and promote its heritage in the face of Chinese occupation.

Yes, but Tibet, despite its unique circumstances, is a large and ancient culture. What I’m getting at is that Ukrainian culture, while facing its own challenges, is not a small or endangered culture. It’s a rich and vibrant tradition with a deep history. It doesn’t need to be “exported” to the West—Americans, Germans, and Dutch should come here and experience it for themselves.

The greatness of Ukrainian culture is evident in the fact that many renowned figures traditionally associated with Russian culture, like Tchaikovsky and Gogol, were Ukrainian. This highlights how deeply Ukrainian culture has influenced and radiated beyond its borders.

So, to answer your question, I believe in focusing on the local, on specific elements like a particular poem or language, rather than exporting culture as if it were something that needs to be preserved by being sent elsewhere. Ukrainian culture is expansive and rich enough that it stands strong on its own without needing to be packaged and shipped off.

***

The Ukrainian Week extends its sincere gratitude to Natalia Tkachuk for translating the original interview from Polish to Ukrainian.