In this article for The Ukrainian Week, Prof Viktor Kozyuk, Doctor of Economics and Head of the Department of Economics and Economic Theory at the West Ukrainian National University, along with Yaroslav Sydorovych from the European Cooperation Agency, examine the implications of the “21st Century Peace through Strength Act,” recently ratified by the US Congress. They underscore its equivalent significance to legislation addressing financial aid and weaponry for Ukraine’s defence. This US law grants the President unprecedented authority to divest Russia of its property rights sans judicial proceedings, thereby facilitating the transfer of assets protected by sovereign immunity to the Ukraine Support Fund.

***

The tumultuous events unfolding on Capitol Hill in the last weeks of April 2024 sparked hope for victory against the Russian aggressor waging war against Ukraine. The legislation, bearing the evocative title ’21st Century Peace through Strength Act,’ passed by both the US House of Representatives on April 20 and the Senate on April 23, carries no less significance comparable to the bill providing financial aid and weaponry for the defence of Ukraine, Israel, and Taiwan, totalling $95 billion. It introduces tangible legal frameworks of a non-military nature aimed at halting aggressions, granting the US President authority to impose specific sanctions on Russia and Iran.

The legislation reflects the collective efforts of diverse expert groups spanning international law, economics, finance, and communications. A pivotal component of H.R.815 is Division F, known as the ‘Rebuilding Economic Prosperity and Opportunity for Ukrainians Act’ or simply the ‘REPO for Ukrainians Act.’ Its provisions play a crucial role in compelling Russia and its allies to halt their aggression while also sending unequivocal signals to G7 nations and other partners regarding the urgent necessity of implementing financial accountability mechanisms for Russia.

The law now formally defines the term “Russian aggressor state” to encompass both the Russian Federation and, if determined by the President, Belarus, should it engage in an act of war against Ukraine in connection with Russia’s ongoing invasion since February 24, 2022. Moreover, the legislation empowers the President of the United States to redirect the sovereign assets of the aggressor state. Meanwhile, the existing laws of Ukraine and EU member states lack a comparable legal mechanism and terminology for reallocating assets and introducing new purposes.

Essentially, this law grants the US President the authority to strip the aggressor state of property rights without judicial proceedings.

It allows for the redirection of assets, protected by sovereign immunity, to the Ukraine Support Fund established in the US and an international fund named the ‘Ukraine Compensation Fund,’ likely to be set up by a coalition of partner states, possibly in The Hague.

This legal mechanism isn’t novel and has long existed in the United States, enabling the confiscation of funds from countries with which the US is in a state of armed conflict or that have attacked the US. Past American presidents have utilised asset forfeiture against countries like Cuba, Venezuela, and Iran.

Debate and adoption of a package of bills in the U.S. Senate on April 23, 2024

The most recent instance of employing this mechanism was under Joseph Biden, who signed an Executive Order on February 11, 2022. It facilitated the diversion of certain U.S.-based assets belonging to Afghanistan’s central bank, Da Afghanistan Bank, from frozen Afghan reserves after the Taliban assumed control of the country in mid-August 2021. These assets, totalling nearly $3.5 billion, were directed towards the Trust Fund to aid organisations providing humanitarian assistance to Afghans. Additionally, funds were allocated to support ongoing lawsuits by American victims of terrorism, including those against the Taliban by families of victims of the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, amounting to $3.5 billion.

The complexities of this mechanism are highlighted by District Judge George B. Daniels’ ruling in New York on February 21, 2022, which barred the enforcement of the second part of the US President’s order. The judge determined that the plaintiffs lacked entitlement to Afghan assets, as US courts lacked jurisdiction to seize them. Doing so would entail recognising the Taliban as Afghanistan’s legitimate government. Since Russia hadn’t engaged in aggressive military actions against the United States, the existing regulations couldn’t be applied. Therefore, adjustments were necessary concerning Russia, a country that consistently and flagrantly violated international law.

Russia was aware of this mechanism and was wary of US actions, reducing the share of US dollar-denominated assets in its sovereign wealth funds over and over again.

Changes in assets issued in US dollars, in the reserves of the Central Bank of the Russian Federation and the National Welfare Fund (RNWF) (geographical feature – USA). Source: Russian Ministry of Finance https://minfin.gov.ru/ and the Bank of Russia https://www.cbr.ru/

The Russian central bank used to release annual reports detailing the geographical distribution of its foreign currency assets based on the location or registration of legal entities acting as counterparties to the Bank of Russia or foreign issuers of securities. However, these disclosures ceased in 2022. Within the Reserve Fund of the Russian Federation, assets linked to the United States consistently represented over 40% of total assets and peaked at $200.9 billion in early 2021.

After sanctions were imposed in 2014 following the Russian occupation of Crimea, there was a noticeable decrease in foreign currency assets issued by the US. However, as of early 2022, they still stood at a significant $40.4 billion, comprising 6.4% of Russia’s total reserves.

The Russian Ministry of Finance, responsible for managing the National Wealth Fund, which is funded by revenue from oil, gas, liquefied natural gas, and petroleum products exports, swiftly reduced the amount of US currency in the fund. This reduction followed a peak of $57.23 billion in March 2020, and as of July 2021, there have been no US dollars in its accounts.

H.R.815 specifically targets various ‘Russian sovereign assets,’ encompassing funds and properties held by entities such as the Central Bank of the Russian Federation, the Russian National Welfare Fund, and the Ministry of Finance of the Russian Federation. Additionally, it extends to any other funds or properties owned by the Government of the Russian Federation, regardless of the specific subdivision, agency, or instrumentality involved.

It’s conceivable that US authorities observed the absence of US dollar-denominated assets in the Russian National Welfare Fund (RNWF), making the inclusion of this fund in the law more of a symbolic gesture.

The law primarily aims to incentivise partners to enact similar legislation for confiscating Russian sovereign assets under their jurisdiction.

Over the 22-month period from March 2022 to December 2023, Russia withdrew assets worth over €51.6 billion, £5.4 billion, and 809.8 billion Japanese yen from the RNWF, equivalent to more than $67 billion. This figure might actually be higher since it was calculated based on month-start balances without accounting for monthly expenditures, and data on these transactions are unavailable for analysis.

Since January 2024, the RNWF has not held assets denominated in the currency of what Russia defines as the so-called ‘unfriendly” nations’. As of April 1, 2024, the Fund has assets in rubles, 227.62 billion in Chinese yuan, and 334.86 tons in monetary gold. Unfortunately, it is no longer possible to seize any money from the Fund’s assets as time has passed. The U.S. Treasury Department’s data reveals that Russia and its residents have significantly reduced their interactions with U.S. financial institutions in recent years and are now choosing to work with European countries instead.

While Russians owned a record $222.77 billion worth of U.S.-issued securities as of July 1, 2008, by July 1, 2022, this figure had plummeted to just $3.464 billion. This underscores Russia’s premeditated preparation for war and its efforts to mitigate the potential consequences of U.S. sanctions.

Dynamics of ownership by Russia and its residents of securities issued in the United States. Source: US Treasury

To present a balanced perspective, the US Treasury Department has provided a disclaimer regarding the data on its portal. “Some foreign owners choose to store their securities with institutions located neither in the United States nor in the owner’s country of residence. For instance, a German investor might acquire a U.S. security and place it in the custody of a Swiss bank. In both the SLT and the periodic surveys of holdings of long-term securities, such holdings are typically recorded as being affiliated with Switzerland rather than Germany. This ‘custodial bias’ results in significant recorded holdings in major custodial centres, including Belgium, the Caribbean banking centres, Luxembourg, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom.”

In essence, this means that if the Central Bank of Russia buys US Treasury bills from a German bank and stores them with a Swiss bank, the holdings would be registered in the US Treasury system – Treasury International Capital (TIS) – as being associated with Germany, not Russia. To ensure the effectiveness of the sanctions, partner countries will need to establish not only an efficient exchange of detailed financial information on sanctioned individuals’ assets but also create an international Register of Assets of Russia and its residents subject to sanctions.

The Law’s operative part states: “Approximately $300 billion of Russian sovereign assets have been immobilised worldwide. Only a small fraction of those assets, estimated at 1 to 2 per cent, or between $4 billion and $5 billion, are reportedly under the jurisdiction of the United States.”

This statement gives no reason to expect that Russia will be deprived of a significant amount of sovereign assets in the United States.

However, the analysis of the available information does not support the congressmen’s expectations. While as of the end of January 2022, Russia and its residents owned $4.5 billion worth of Treasury securities in the United States, by the end of February 2024, Russians owned only $47 million worth of short-term Treasury securities.

The dynamics of ownership by Russia and its residents in U.S. Treasury securities. Source: US Treasury

The fact that the Russians were able to receive funds from the redemption or disposal of $2.092 billion (in November 2022) and $629 million (in December 2022) of Treasury securities suggests that their recipients were not subject to US sanctions at that time. It is reasonable to assume that the $47 million worth of Treasury securities are unlikely to be associated with the Central Bank of the Russian Federation or any state agency owned by the Russian government.

In this scenario, these assets would not be eligible for reprofiling (confiscation) under the law, which applies solely to assets owned by Russia or Belarus. If an individual residing in Russia is listed on the U.S. sanctions list, their assets will remain frozen until active criminal actions are attempted or the sanctions are lifted.

It’s worth noting that only Ukrainian legislation (Law of Ukraine No. 2257-IX dated May 12, 2022, ‘On Amendments to Certain Legislative Acts of Ukraine on Improving the Effectiveness of Sanctions Related to the Assets of Individuals’) and Canadian legislation (Section 32 of Bill C-19 dated June 23, 2022) contain provisions allowing for the confiscation of assets of individuals and legal entities under sanctions through court proceedings. As of December 2022, these laws have been implemented.

According to the ‘How to Confiscate Russian Assets in Ukraine?’ platform, as of April 25, 2024, the special fund of the state budget has received UAH 25.9 billion from confiscated property resulting from completed court proceedings. The Ministry of Justice of Ukraine continues to successfully initiate lawsuits for the confiscation of assets belonging to sanctioned individuals.

It might be feasible to locate and seize assets owned by Russian government entities in the United States. For instance, Czech activists managed to identify and pinpoint 23 real estate properties in central Prague belonging to the ‘Goszagransobstvennost’ enterprise, which operates under the Russian Presidential Administration.

Czech activists identified and mapped 23 real estate properties in the centre of Prague belonging to the Russian state Goszagransobstvennost enterprise.

The issue of economic sanctions and asset confiscation strikes a sensitive nerve with Russians, often eliciting vehement reactions from the ruling elite. In response to the West’s intentions to escalate efforts in depriving Russia of its resources, there have been instances of threatening nuclear retaliation. This factor could explain the reluctance of EU leaders to follow through on promises to confiscate Russian assets. It’s reminiscent of the Cold War doctrine of mutually assured destruction, which posits that the use of weapons of mass destruction by both sides would result in mutual annihilation, rendering any first-strike attempts futile.

While it seems improbable that the Kremlin elite would resort to nuclear weapons in response to asset confiscation, they may resort to other measures. For instance, following the passing of the Russian Assets Act by the U.S. Congress, State Duma Speaker Vyacheslav Volodin conveyed the official stance of the Russian authorities, hinting at potential retaliatory measures: “Our country now has every reason to make symmetrical decisions regarding foreign assets.” Given Russia’s history of expropriating property, both domestically and in occupied territories, his words carry weight.

In March 2020, Russia’s Vladimir Putin transformed Crimea into a military stronghold by signing a decree that prohibited non-Russian citizens and foreign legal entities from owning land in Crimea and Sevastopol, effectively confiscating their property. Following the full-scale invasion, the trend of expropriating property belonging to subsidiaries of Western companies in Russia became rampant. Putin’s decrees euphemistically term this act as “transferring to management” by Kremlin-controlled entities. A notable instance occurred on December 19, 2023, when Putin signed decrees stripping Austrian OMV and German Wintershall of their shares in joint ventures with Gazprom, responsible for developing the South Russian field and Achimov deposits of the Urengoy field. These assets’ rights and obligations were then transferred to a government-established LLC, with Sogaz and Gas Technologies invited to become co-owners.

Consequently, Congress’s decisions prompted swift repercussions concerning the affected companies’ US assets. On April 22, the Arbitration Court of St. Petersburg and the Leningrad Region issued an order to freeze all funds in JPMorgan Chase’s bank accounts, including correspondent and subsidiary accounts. Last week, JP Morgan Chase filed a lawsuit against VTB in New York to prevent the latter’s efforts to recover $439.5 million from accounts frozen after Russia’s incursion into Ukraine in 2022, for which VTB faced sanctions.

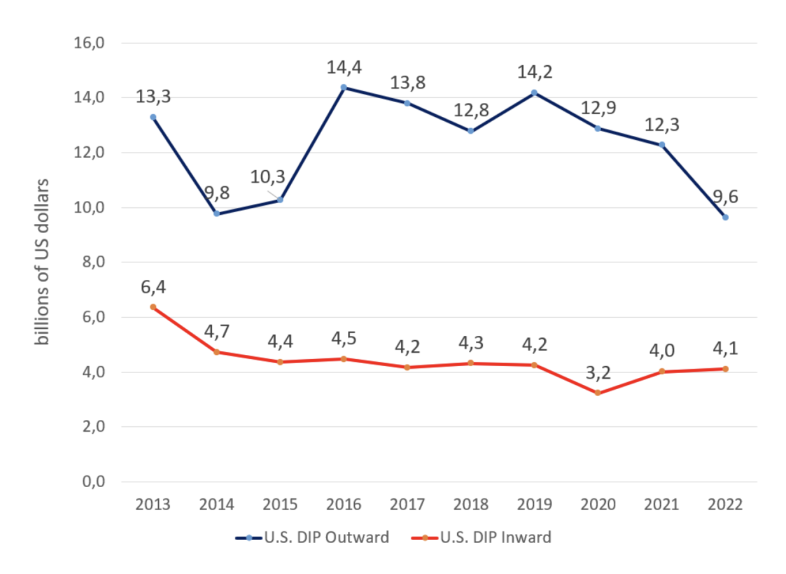

According to the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, as of January 1, 2022, the position of U.S. direct investment in Russia (outward) amounted to $9.6 billion. In 2021, 191,900 people worked in the Russian subsidiaries of American companies; sales amounted to $52.8 billion. Direct investment from Russia to the United States (outward) amounted to $4.1 billion. In 2021, the subsidiaries of Russian multinational companies located in the United States employed 3,300 people and had sales of $5.5 billion.

Dynamics of the US position on foreign direct investment with Russia. Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

It’s certainly tempting for Russian authorities to seize the assets of highly profitable American companies operating within Russia, especially considering the limited risk of a significant retaliation from the United States.

The economic ties between the two nations have significantly dwindled over time. In 2023, the value of goods and services exported from the United States to Russia stood at $2.3 billion, a decrease of 52.2% from 2022 and a staggering 8-fold drop from 2014’s figure of $17.4 billion. Similarly, imports from Russia amounted to $5.4 billion in 2023, down by 65.9% from 2022 and 5 times less than the $25.8 billion recorded in 2014. Currently, trade between the United States and Russia accounts for less than 0.1% of total US trade.

Dynamics of exports of goods and services from the United States to Russia

and imports of goods and services to the United States from Russia. Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

Therefore, it’s crucial to shift our focus towards ramping up financial actions on the European continent.

As per the Law’s operative section: “The bulk of immobilised Russian sovereign assets, around $190 billion, are reportedly within the jurisdiction of Belgium. The Belgian Government has publicly stated that any action concerning these assets would hinge on support from the G7.”

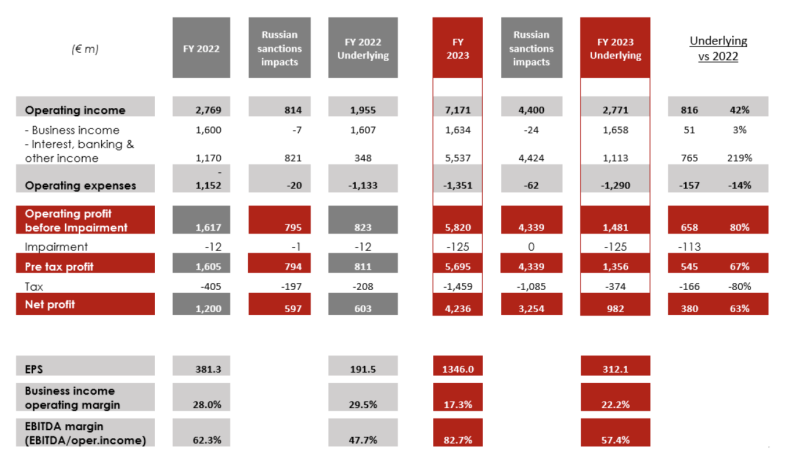

It’s worth acknowledging the conscientious approach of Euroclear Group employees, who, since the imposition of sanctions against Russia, have diligently maintained separate records for sanctioned assets. They’ve ensured that “sanction-related earnings from Russia are kept distinct from the underlying financial results and retained until further guidance is provided on their distribution or management.” These earnings are also reflected in their public reporting.

A thorough examination of Euroclear Group’s structure highlights that the decision to seize the assets of the Russian Central Bank’s reserves should involve not only the governments of EU countries but also those of the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, and Australia. These countries, as issuers of securities, bear legal obligations to redeem these securities and pay coupon income.

Source: Euroclear Group’s 2023 report

The majority portion of the CBR’s frozen reserves consists of assets denominated in euros (63%), likely managed by Euroclear France in France and Euroclear Belgium in Belgium. The remaining assets in the CBR reserves, comprising pounds sterling (16%), Canadian dollars (9%), US dollars (8%), and Australian dollars (3%), are under the purview of Euroclear UK & International, a UK-based central securities depository serving the US, Canadian, Australian, and New Zealand markets.

The category “Other—1%” signifies the presence of assets worth nearly €2.5 billion denominated in Swedish kronor, Danish kronor, Swiss francs, and Norwegian kroner, which the Central Bank of the Russian Federation preferred in past years.

Balances related to Russian sanctions. Source: Euroclear Group’s 2023 report

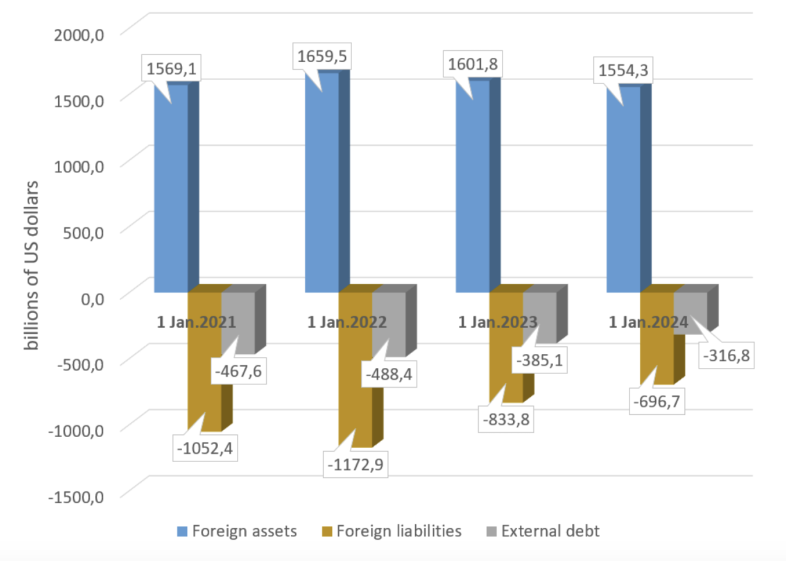

To the dismay of European politicians, Western countries stand a strong chance of prevailing in a mutual confiscation scenario. Russia’s total foreign assets significantly surpass its foreign liabilities and external debt; in the past two years alone, Russia’s net international investment position has surged from $485 billion to $876.4 billion. As of March 1, 2024, Russia’s foreign assets tallied up to $1547.1 billion, amounting to 4.7 times its foreign debt and 2.3 times its foreign liabilities.

Since the onset of the full-scale invasion, Russia has been concealing many vital economic indicators. However, the available data on Russia’s external debt structure as of January 1, 2022, reveals debt amounts of $205.1 billion and €97.1 billion. As of April 1, 2024, the external debt stands at $304.0 billion in equivalents.

Foreign assets, liabilities and external debt of Russia (2022-2024). Source: Central Bank of Russia

As of January 1, 2022, foreign direct investment in the Russian economy totalled $610.1 billion, with equity participation at $474.7 billion. Investments from “unfriendly countries” amounted to $553.3 billion, comprising 89.3% of all investments, with equity participation at $424.0 billion. The Russian authorities could potentially expropriate assets invested from these “unfriendly countries” up to this amount. However, these assets are secured by bilateral agreements that mutually protect investments. Yet, seeking protection through international courts can be time-consuming and not always successful, given Russia’s history of non-compliance with court decisions. For instance, in the arbitration case involving Yukos shareholders against Russia, which spanned from 2005 to 2024, Russia was ordered to pay $50 billion in compensation. The timeline and means for fulfilling this compensation remain uncertain.

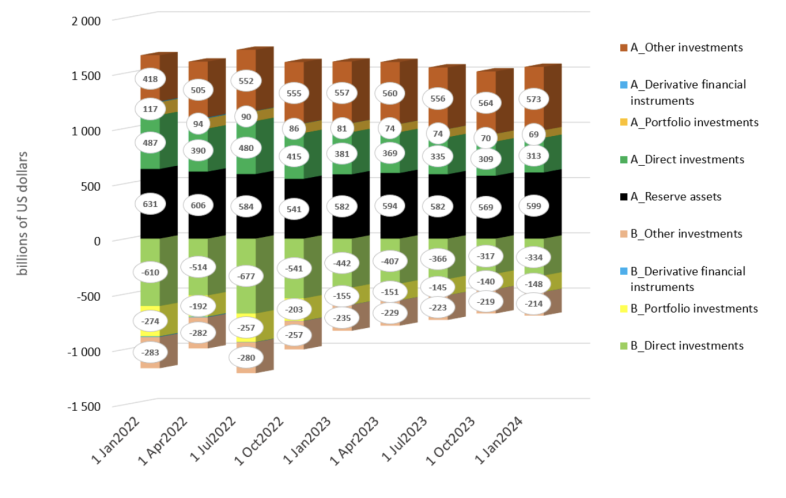

Dynamics of the international investment position of the Russian Federation (2022–2024). Source: Central Bank of Russia

It’s crucial for Western countries to actively safeguard their companies that have already lost or may face the loss of assets in Russia. They need to establish mechanisms to offset losses resulting from the confiscation of Russian assets in Western nations. Russia will seek out a vulnerability and set a precedent for swapping assets of Western companies on its turf for those blocked by sanctions. From a purely mathematical standpoint, both asset exchange and compensation for losses from confiscated assets lead to the same outcome. However, in asset exchange, Russia evades accountability and appears as a trustworthy partner. Among the significant assets Russia will likely leverage for such exchanges are a series of 13 issues of Eurobonds issued under the names RUS in US dollars and Euros, with maturities ranging from 2025 to 2024, amounting to a total of $19.7 billion.

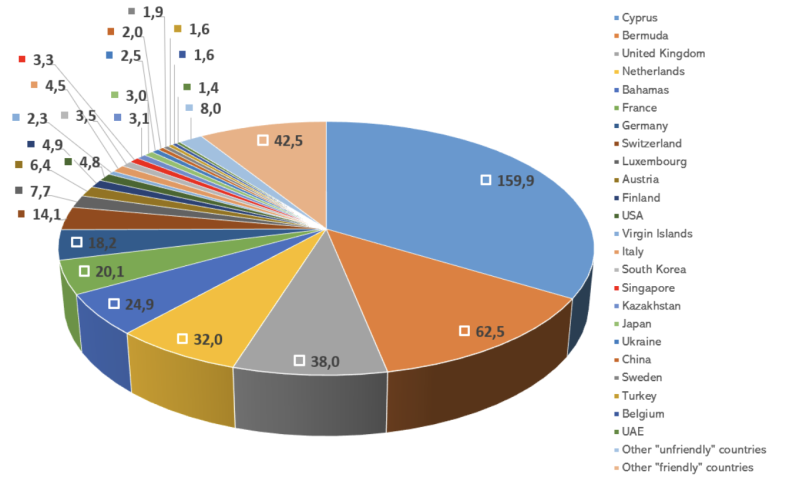

Foreign direct investment in the Russian economy by country as of January 1, 2022 (in $ billion). Source: Central Bank of Russia

The largest influx of foreign direct investment into the Russian economy came from investors based in Cyprus, amounting to $159.9 billion, followed by Bermuda with $62.5 billion, the United Kingdom with $38.0 billion, the Netherlands with $32.0 billion, and the Bahamas with $24.9 billion. It appears that investments from offshore companies might represent a return of a portion of funds siphoned out of Russia through clandestine channels, which the Russian authorities may not target for expropriation. However, genuine investors from “unfriendly countries” could find themselves in the Kremlin’s sights and become subject to retaliation. Overall, as of early 2022, Russia had invested $487.0 billion in other countries, with Russian companies contributing $455 billion to the economies of “unfriendly” nations. Much of these assets are held by Russian residents—both legal entities and individuals—listed on sanctions rosters and, therefore, subject to blocking measures.

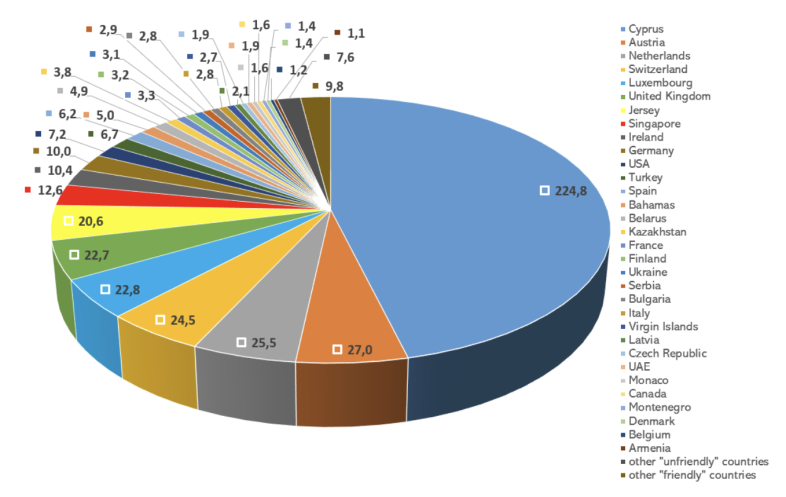

Russian direct investment in the economies of foreign countries as of January 1, 2022 (in $ billion). Source: Central Bank of Russia

Over the past two years, Western companies have utilised diverse strategies to recover some of their investments, significantly reducing their presence in the Russian economy to $333.7 billion by early January 2024. Despite the Russian government’s cessation of detailed information disclosure, alternative statistics can be obtained from other countries. It’s imperative to acknowledge that in a scenario of reciprocal asset confiscation, each individual nation may find itself disadvantaged against Russia. This stems from the Kremlin’s history of brazenly flouting international law, contrasted with the adherence of democratic nations to the principles of the rule of law. Only through a united coalition of states, reminiscent of a “Financial Ramstein,” can countries aspire to counter Russia’s economic sway, shield their affected companies from the caprices of Russian authorities, and fully compensate for losses by seizing assets belonging to Russia and its residents.

Under the Law, the President of the United States has been granted extensive powers to “lead robust engagement on all bilateral and multilateral aspects of the response by the United States to acts by the Russian Federation that undermine the sovereignty and territorial integrity of Ukraine, including on any policy coordination and alignment regarding the repurposing or ordered transfer of Russian sovereign assets in the context of determining compensation and providing assistance to Ukraine.”

Congress has stated that any attempt by the United States to seize and reuse Russian sovereign assets must be carried out in conjunction with international allies and partners as part of a coordinated, multilateral effort. This effort includes G7 countries, the European Union, Australia, and other countries where Russian sovereign assets are located.

An effective approach to address a wide array of economic issues would entail a “Financial Ramstein” format involving G7 countries, the European Union, Australia, New Zealand, Norway, Ukraine, Switzerland, and interested partners. This format would aim to synchronise sanctions lists, maintain the Register of Blocked Assets of Persons Under Sanctions, and establish effective legal mechanisms of financial accountability for aggression through the confiscation (re-profiling) of assets of Russia and its residents, with their transfer to the International Compensation Fund in The Hague.

The financial war’s frontline must be fortified for the democratic coalition to succeed in deterring Russia, freeing Ukraine, compensating for losses, and promoting global political and economic stability. Coordinated actions are necessary for achieving these goals.