The Belarusian society was rather shaken by the events that unfolded in the Ukrainian capital in early 2014. Armed clashes in the centre of Kyiv, scenes of protesters being shot at Instytutska st. made a daunting impression on the citizens of the neighboring country, with the prevailing sentiment being: “No, this kind of democracy we'd rather do without!”

According to the survey by the Independent Institute of Socio-economic and Political Studies (IISEPS), in June 2014 the Belarusians felt strongly negative about the Maidan, although the question contained an important provision: “Considering the post-Maidan developments in Ukraine, how do you feel about the Euromaidan and the ousting of president Yanukovych?” At that point, in mid-2014, 63.2% of respondents felt negative, with the positive response given by only 23.2% of the surveyed. This is not surprising, firstly, given the deaths in the centre of Kyiv, and, secondly, by then Crimea had already been snatched, and the chaos in Donbas had already began. The biggest and perhaps the most important factor in all was the influence of the Russian television, which is readily available in Belarus. So much so that, for example, the Russian channels RTR and NTV are part of what is called the "social package", which is aired via the nationwide broadcasting network. They aren't even cable or satellite channels, they are on equal footing with the Belarusian state-owned TV. Regular Belarusians saw Ukraine through the prism of the Russian interests and the Kremlin's propaganda.

The Belarusian people, which, according to the most recent studies, lost one third of its population during World War II, developed a very strong aversion to war of any kind. “As long as there's no war” (Soviet-era expression mostly used in place of ‘could be worse’ – Ed.) can practically be considered the national motto for a regular Belarusian. To such a great degree that the citizens, while acknowledging the direct threat to their country, aren't prepared to defend it.

RELATED ARTICLE: Alexander Motyl: "Ukraine is important to the US as a counterweight to Russia"

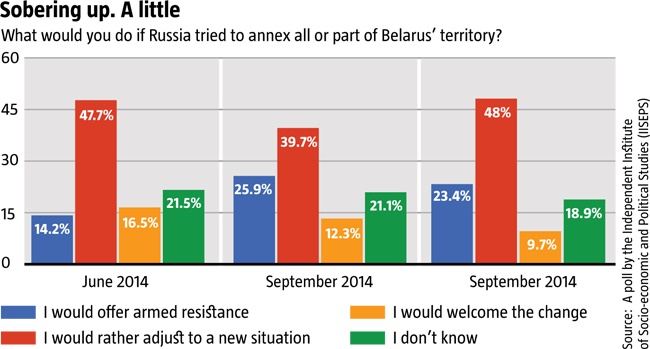

At that time, in June 2014, 67% of citizens believed that Russia may annex part of Belarus or its entire territory. Opinions spread from “possible, but unlikely” (36.4%) to “it is inevitable” (4.4%), but such a threat was largely acknowledged. And at the same time only 14.4% expressed readiness to take up arms to resist it. 47.7% would rather "adapt to the situation" and 16.5% would even "welcome such changes".

At that time, in June 2014, 67% of citizens believed that Russia may annex part of Belarus or its entire territory. Opinions spread from “possible, but unlikely” (36.4%) to “it is inevitable” (4.4%), but such a threat was largely acknowledged. And at the same time only 14.4% expressed readiness to take up arms to resist it. 47.7% would rather "adapt to the situation" and 16.5% would even "welcome such changes".

By January 2015 the trends did not change significantly. Although the percentage of those willing to defend Belarus grew by 9% (to 23.4%), and the demographic welcoming the annexation by Russia shrunk to 9.7%, nevertheless the percentage of ‘opportunists’ remained the same – 47%.

Russia's information war

The IISEPS sociologist and political analyst Siarhei Nikaliuk believes that the Maidan along with the ensuing events in Ukraine brought home just how decisive is the influence of the Russian propaganda on the Belarusian society. “Belarus is positioned inside the information space of the Russian Federation. And nearly 60% of population or more are receptive to the Russian interpretation of events. That is why they perceived these events the way Russians did: they were overcome with euphoria about Crimea becoming Russian. As a result already in March 2014 emerged the situation that I labeled ‘Anomaly-2014’. The rate of income growth among the population began to slow down and by the end of the year reached zero, if not negative values. And the Belarusians have grown accustomed to associating economic stability with doubling income, which is exactly what we had for 10 years. The anomaly lies in the fact that during the economic downturn the support of the authorities and Lukashenka in particular went up,” says the sociologist.

The results of the first survey of 2015, according to Nikaliuk, show that the anomaly is running out of steam somewhat, especially after the devaluation of the Belarusian ruble in late December 2014, but it is still apparent. “We recorded the perceived catastrophic drop of living standards among the citizen, but their trust in the authorities remains quite high. The electoral rating of Lukashenka dropped to 34.2%, but the trust level is still abnormally high at 48.8%. And that’s while 46.3% stated that their financial situation has worsened,” says the analyst.

RELATED ARTICLE: Russian military bases around NATO borders and in Central Asia

So why did the Belarusians go all euphoric about Russia grabbing Crimea? It's simple, according to Nikaliuk: they associated themselves with Russians. “One of the basic elements of Russian culture, and no one is going to challenge the fact, is its imperialism. And what I say (causing a bit of a stir among my colleagues) is that it is also characteristic of many Belarusians, as much as the Russians. Imperialism is a trait of homo sovieticus. Our famous compatriot Alies Adamovich was onto something, when he called Belarus the ‘Vendée of perestroika’. According to one of the early polls conducted throughout the entire Soviet Union in 1991, prior to the collapse of the USSR the percentage of homo sovieticus in Belarus was the highest of all the Soviet republics. To remind, at the time the question read: do you consider yourself a citizen of the USSR or a citizen of your republic? In their ‘sovietness’ Belarusians came ahead of all the republics of the former Soviet Union, it was the most soviet nation,” Siarhei Nikaliuk says.

Therefore the imperialism is perceived by them as something close to their hearts, and all the while the Russian propaganda bolsters the imperialist mindset. “The Russian propaganda in Belarus fell on fertile ground. It awakened and unearthed what was buried inside a soviet Belarusian,” believes Nikaliuk.

“The propaganda created two levels of perception amongst Belarusians. One being the economic one (the decline in living standards is perceived quite objectively), the other one being symbolic (the attitude towards the authorities and the state). And these perceptions live two separate lives. we don’t yet observe the expected decline in the symbolic level following the decline of the real one. It's quite a mystery for sociologists,” Nikaliuk says.

Maidan killed the ploshcha

In the run up to the presidential election in Belarus, which is to take place no later than November 2015, the opposition found itself in a dismantled state. The inability to agree in order to come forward with a single candidate has always been a problem for Belarusian opposition politicians. That's what occurred in 2006, when two democrats, Aliaksandr Milinkevych and Aliaksandr Kaluzin, ran for president. Same transpired in 2010, when the inability to reach an agreement resulted in a “parade of candidates”. In the end the authorities made sure that votes were counted in a way that gave opposition leaders under 2% each, and some of them ended up in jail, including Mikalay Statkevych, who remains in prison to this day.

Many Belarusian opposition leaders visited the Maidan to support democratic change in Ukraine. Much like in 2004 during the Orange Revolution they hoped that the democratic Ukraine would pave the way for democratic change in Belarus.

After the shooting of protesters at Instytutska St. in Kyiv the Belarusian society turned away from any ideas about having anything like the Maidan. This left the opposition without its mobilizing idea – its own ploshcha, the square, where Belarusians attempt to demonstrate to the authorities by means of peaceful protest that there are many in the country of those, who are at odds with the government's policy, as well as the official election results. In different moments in time rallies in Belarusian squares had different goals: from attempts to get the authorities to re-count the votes, to making them take notice of the opposition and its views. Now, after the bloodshed in Ukraine, the square is no longer on the agenda. The opposition basically lost its only mobilizing tool for its presidential campaign.

RELATED ARTICLE: The origins of Donetsk separatism

The protest vote in Belarus makes 25% of all voters. And these 25% are willing to support the single opposition candidate largely regardless of who this candidate is. The "mobilization" of this demographic was always tied to the square. Towards the end of an election day the supporters of the opposition would gather at the main squares of Minsk in order to “either celebrate the victory or make the authorities return the stolen votes”. This call traditionally was the main mobilizing force for the voters: even in case of defeat the opposition just wouldn't give up.

After the Maidan, though, things changed dramatically. Following the events in Ukraine Belarusian opposition leaders are not simply fearful of the square as a form of protest. They're afraid of what might happen, if the protest was suddenly to succeed.

In such a case, many believe, the Russian Federation may launch the “Ukrainian scenario” in Belarus, which in a society completely hooked on the Russian television, one that is basically part of the Russian media-sphere, will lead to loss of sovereignty and independence. Which is why the central theme for the opposition at the next election is preserving sovereignty and independence. So this time it is to avoid mass protests on the streets not to rub Russia the wrong way, to avoid providing the Kremlin an excuse to interfere in Belarus.

There's even a new saying making the rounds among the public: “Better Lukashenka Aliaksandr than a Russian Ivan on a tank”.

In 1997, when Lukashenka was on a roll signing documents for the creation of a union of Belarus and Russia, I had the honor to meet dissident Valeriya Novodviorskaya in Moscow. As we wrapped the interview she said: “You will see the day when Lukashenka fights for the independence of Belarus in a trench with a gun in his hand”. Back then this seemed preposterous: the president, who is “selling off” the country, to fight for its sovereignty? Fast forward almost 20 years and… it turns out Lukashenka, according to, perhaps not publicly voiced, but clearly implied view of the Belarusian opposition, is the guarantor of sovereignty and independence of Belarus. Novodviorskaya saw this coming way back!

Lukashenka's setback

From the very beginning Aliaksandr Lukashenka was less than thrilled about Russia's actions in Crimea and Donbas. Moreover, he was the first to get the chills about such a turn of events. Granted, Russia is the main partner of Belarus in all areas: political, military and economic, but Ukraine is also extremely important being the third biggest (after Russia and the entire EU) trade partner.

Russia's actions in Crimea violated the Budapest Memorandum, which guaranteed Ukraine territorial integrity and inviolability of borders in return for giving up nuclear weapons. But the thing is that the aforementioned memorandum envisaged the very same guarantees for Belarus. So the fact that one of the "guarantors" defied this document naturally caused serious headaches for the Belarusian leader.

RELATED ARTICLE: How effective is the Russia-led Customs Union?

Which is why since the early days of the conflict Lukashenka tried to distance himself from the Russian Federation. It's worth mentioning the meeting that he had with the then acting president of Ukraine Oleksandr Turchynov, at which Lukashenka promised to do everything in his power to ensure his support and mutually beneficial cooperation.

Also evident is the fact that the Belarusian leader made the right conclusions from the Russo-Ukrainian conflict. During the course of 2014 he focused heavily on the development of the Armed Forces of Belarus. Among the results of this was the development of new military machinery unveiled during the May 9 parade in Minsk.

Of course, Lukashenka did recognize the occupied Crimea as part of Russia, in words at least. The Belarusian leader presented his views at the large press-conference on January 29, 2015: “You know about my position regarding Crimea. You've had it coming. If you consider it to be your territory, you should have fought for it. And since you didn't fight, it's not yours”.

This, however, does not necessarily imply his support of Russia in the Crimean matter. His interpretation of events never translated into concrete legal moves. The Belarusian president himself stated that he had never been approached regarding the official recognition of Crimea, while the recognition inquiries of the Luhansk and Donetsk "People's Republics" sent to the Belarusian parliament had been ignored. One could read Lukashenka's true attitude towards the annexation of Crimea in the policy of the national airline Belavia, which no longer makes flights to the peninsula, thereby fully supporting the view that the occupied territory should be a no-fly zone.

The Russo-Ukrainian conflict gave Aliaksandr Lukashenka the opportunity to improve his relationships with the West. On the one hand, he believes that a stable and peaceful Belarus, albeit with "Europe's last dictator" in charge, is of great value for the West. On the other hand, it is valuable as a venue for peaceful negotiations. The Minsk-1 and Minsk-2 meetings prove this point. On top of that everyone expected the second talks in Minsk to be a major breakthrough in the political blockade held by the EU over Belarus since 1996. After Lukashenka rewrote the Constitution almost 20 years ago the PACE refused to recognize the Belarusian parliament, while the following undemocratic elections and human rights abuse have put the country under EU sanctions and even direct financial sanctions by the International Labour Organization. The latter kicked Belarus out of ILO's General Preference System due to persecution of trade unions. This incurs direct financial losses for the country.

One would have thought that after the visit of François Hollande and Angela Merkel the EU sanctions would be swept under a rug. Surely Lukashenka can't be non-grata in the EU after all the handshakes with Europe's top brass? Turns out, he can.

Contrary to all the predictions regarding the “warming of relationships” with the West, the latter turned out to be more principled than even the Belarusian opposition could imagine. The list of sanctioned officials involved in persecution and election-rigging did not vanish into thin air. And Lukashenka is still unwelcome in Europe, another proof of which is May's Eastern Partnership Summit in Riga. Belarus got the invitation, but not for Aliaksandr Lukashenka personally. Therefore he failed to achieve his goal here.

“The ‘Russian World’ is not about us”

This is what Lukashenka proclaimed during his April 29 address to the people and the parliament. The relationships with Russia, which at first glance may seem to be in perfect health, in reality are anything but healthy. The Belarusian economy is almost fully dependent on the Russian Federation. The crisis in Russia prompted by the plummeting oil prices and the fall of the ruble, had a devastating impact on Belarus. In late 2014 the national currency devaluated by 40%. In times of crisis in Belarus Moscow always used to come to the rescue. But not anymore.

Minsk asked for a USD 2.5 billion loan in early 2015. But the Russian Federation could only provide USD 110 million to its "brother nation". Meanwhile Kyrgyzstan received USD 200 million of gratuitous financial aid (not loan) from Russia for equipping its state border. Such a brazen neglect of Moscow's “main ally” has to mean something.

“The Russian leadership is not very satisfied with the stance taken by Belarus regarding the Ukrainian issue,” says political analyst Andrei Fiodarav, “but it is not being expressed yet. As far as the loan is concerned, it's hard to say what the culprit was: whether it's the Belarusian stance regarding Ukraine, or the fact that Russia itself is in a similarly dire situation, or the failure to meet the obligations, under which previous loans were provided.”

“One cannot definitely see this as a demonstration of displeasure by Moscow. There's no evident displeasure expressed on the political level. The meeting in the frameworks of the Commonwealth of Independent States and the Eurasian Economic Union took place on May 8, and the outward impression is of complete harmony. So Moscow is to tolerate Aliaksandr Lukashenka for a while longer, keeping an eye on his behavior, on whether he keeps within the ‘bounds of decency’,” the analyst says.

RELATED ARTICLE: The concept of routinized totalitarianism as a key to understanding what is at stake in "decommunization" in Central and Eastern Europe

Fiodarav noted that at Lukashenka's large press-conference he made no bones about his concerns regarding the repeat of the Ukrainian scenario in Belarus. Which is why he will stick to certain boundaries set by Moscow.

Aliaksandr Lukashenka finds himself in a position of a “geopolitical pendulum”, which he perfected over the years: threatening Moscow by ‘swinging westwards’ and getting money for staying in the confines of the ‘Russian sphere of influence’, but at the same time simulating reforms and liberalization for the West and getting loans from there as well. There is nothing new or unusual about this: take for example the ‘liberalization’ of 2008-2010, which allowed the Belarusian leader to receive USD 3 billion loan from the IMF in order to bankroll his 2010 election campaign. And we know well how that presidential race ended: Statkevych, mentioned above is still in prison.

Victory or defeat?

With all things considered one can state that in Belarus nobody gained from the Maidan and the ensuing events in Ukraine. The Belarusian society has been bullied into a “pit of fear”. The opposition is demoralized. And while Lukashenka received a good opportunity to normalize the relationships with the West, this potential so far remains untapped. There is no evident change in the relationships with Moscow: the Kremlin continues to keep its “ally” on a short leash. Russia, however, didn't manage to get Belarus to totally adopt Moscow's stance in regards to the events in Ukraine.

All in all, in the spirit of the paradoxical saying that “negotiations are successful when both parties are dissatisfied”, the Maidan and the events in Donbas showed the weak spots of the Belarusian statehood. They include the inability to counter foreign propaganda, East-oriented Armed Forces, one-sided foreign policy, and great many other things that need working on. Whether Belarus is going to work on them, is another question altogether.