All Ukrainians wanted to cast off the yoke of the communist dictatorship and the planned, ration-based socialist economy. What did they obtain after succeeding in doing so? Most people did not receive a better life. The “reforms” were such that fraud and embezzlement of public property were not just permissible but even prestigious.

How can Ukrainians come to terms with this fraudulent and largely criminal business? Most importantly, how can things be put back on the right track? Without a free market and the energy of entrepreneurs, Ukraine will continue to eke out a miserable existence. In this series of articles, I attempt to expose the main problems faced by Ukrainian business and show what alternative paths of development exist. The first instalment is about the importance of free entrepreneurship for the economy and how Ukraine affects it.

It is often said that privately owned companies seek only their own benefit, and the country's economy can do well without them. Following this line of reasoning, state-owned enterprises are the only ones that secure the welfare of the entire nation. Most Ukrainian politicians and government officials subscribe to the idea of seeking an optimal balance between the two types of companies.

Another widespread opinion is that private companies require efficient owners. It follows that, lacking such owners, companies must remain property of the state. There is also the well-known view that all forms of property need to be supported and developed. Is this really true? Evidently, it is not that simple.

ENTERPRENEURIAL PROFIT AS COMMON GOOD

If there is no economic profit, there is no accumulation of capital or investment nationwide, and this means that the conditions for growth in production, more jobs and R&D are not in place. This is axiomatic. Profitability can be found only in a market economic system with private property.

With few exceptions, there was no economic profit under feudalism and previous social systems. The dynamic of economic development was essentially nonexistent. Some people noted that both profitability and investments were part of the planned economy under socialism. Yes, profits indeed existed. But were they economic profits, i.e., the result of economic initiative put into practice? No, they were obtained by confiscating the property, goods and labour of peasants, urban workers and scientific institutions and by expropriating private capital accumulated in tsarist Russia. The Soviet government also claimed land rent and in-kind rent, exploited the military and convicts who did penal labour and earned income on war indemnities and the lend-lease in the Second World War, etc.

The profits were reaped not by enterprises that were economical, innovative or otherwise economically efficient, but by those whose products were sold at prices centrally fixed at a level higher than unit cost. Meanwhile, some other enterprises were forced to sell their products below unit cost, so they were unprofitable according to the economic plan.

Prices were fixed in a centralized fashion, which was the fundamental distinct trait of the planned economy. Profits were reaped by the state and the state then distributed them among certain economic entities. As the sole proprietor of all profits, accumulated capital and investments, it did not need other entities willing to seek and obtain them. That system was fundamentally flawed and could not be successful, because it failed to stimulate entrepreneurial activity, which is the human initiative that leads to the production and realisation of innovative consumer values, the application of innovative production technology and/or the opening of new markets.

The means of production and labour have no sense without entrepreneurial ideas and actions. It is only jointly that means of production, labour and the organisational efforts of entrepreneurs create value and become part of it. Land and monetary capital that are involved in creating value also need to be factored in. This pertains to any industry or type of economic activity, such as the manufacturing industry, commerce, transport, construction, communications, utility services, hotel and restaurant business, legal services and so on.

Some companies receive profits exclusively due to special entrepreneurial qualities, and these profits are the difference between revenue and production costs after interest has been paid on the capital received. Without ownership of a company, a person will not show entrepreneurial qualities. Nor will he channel his own and borrowed money to establish a new enterprise and develop it.

Notably, entrepreneurship plays an active, creative part in the economic process unlike other, passive components.

Entrepreneurship should be distinguished from scientific research, the creation of innovative products, design, branding and building a typical technological process. All these elements are prerequisites for manufacture and business, but without entrepreneurship, they remain on paper only.

Entrepreneurs are producers, but they do not simply implement what has already been designed and developed. On the contrary, they themselves initiate and implement the best of possible products rather than simply promote their own ideas. They also advance their products on the market, seek the best and most favourable markets, and create and increase value.

This special entrepreneurial process yields better products, the highest productivity, minimum costs and the best supply/demand ratio. The output may include any consumer goods – products, services, information, etc.

Another important trait of entrepreneurs is their contribution to creating value and generating revenue. Other components – land rent, equipment cost, payroll and bank interest – are relatively stable quantities determined by average market values.

Entrepreneurial profit, just like the efforts of entrepreneurs, is in no way linked to average values. This performance indicator is always individual and depends on the specific invention as well as on consumer perceptions.

Entrepreneurial profit is, as a rule, short-lived. Its maximum value is achieved at an initial stage when new production ideas are implemented or a new good is manufactured, as long as it is unique.

With time, others begin to master the new production methods, production volume grows and higher demand for such innovations is met. Then the size of the entrepreneurial profit decreases, while other components of net profit (rent, interest, payroll and depreciation) remain virtually unchanged.

Entrepreneurial profit disappears completely when organizational and technological improvements spread throughout the industry and when no one has an individual advantage in terms of economy, or when a new product begins to be manufactured by all competing companies and consumer demand is fully met.

Thus, entrepreneurial activity as such is creative, because it develops production. An entrepreneur cannot afford to rest on his laurels. His stimuli are of a special and extraordinary kind. Entrepreneurial profit may be superhigh if his proposal is revolutionary, as was the case with the railway and the steam engine or, more recently, the Internet and its new operational capabilities.

By standing still, an entrepreneur risks losing everything and going bankrupt. There is no development, organization, enrichment and progress of society without entrepreneurial activity.

ENTREPRENEURIAL ACTIVITY AS AN ENEMY OF THE PLANNED ADMINISTRATIVE ECONOMY

Why did socialism remove entrepreneurs, and can the CEOs of Soviet plants and factories (and chiefs of ministries and agencies) be called entrepreneurs? In some cases, Soviet directors exhibited entrepreneurial qualities: they reequipped their plants, implemented better technology, serialized new products, optimized production capacity, etc.

But they never became entrepreneurs. First, they did not receive any of the profit resulting from their innovations. Instead, they only received their salaries which, truth be told, included various bonuses and stimuli, special one-time payments for technical upgrades and personal benefits awarded by ministries.

In other words, such improvements could never materialize without the consent of the owner (the state, or its ministry), which viewed plant directors exclusively as hired labour. Second, the changes made at state-owned enterprises were not, in essence, innovations because they only replicated — in a planned economy — the achievements of other entrepreneurial entities, which were normally located abroad. Typically, they did so inaccurately, because foreign models often had to be modified or altered.

These Soviet novelties simply propagated innovations already present on other markets. The best equipment used in the most advanced sectors of the Soviet economy (microelectronics, radio electronics, electronic engineering and rocket construction) was foreign-made.

In general terms, three waves of technological import may be singled out: during industrialization; after the Second World War (American lend-lease and war indemnities imposed on Germany); and in the 1970s and 1980s, when a strong flow of petrodollars after crises in world energy allowed the USSR to purchase new equipment in the West.

Soviet constructors who designed products that were serialized by the industry, from footwear to cars to ships and nuclear reactors, were copied from foreign specimens, including those procured by the Soviet special services.

ENTREPRENEURS NEED THE OPEN SEA AND FINANCIERS NEED QUIET HARBOURS

What is the connection between entrepreneurship and investments? Where do investments come from to meet the needs of entrepreneurs? The source of these investments is citizens, groups of citizens or nations that invest in manufacture, business and transactions in order to receive profits. If investments are made by private individuals who seek the highest return, they will most likely go precisely to entrepreneurs.

Entrepreneurial activity and financial business are fundamentally different. The former seeks to bring together factors and components of the production process to create supply on the market of consumer goods, while the latter is aimed at profitable and risk-free investment of money and is not much concerned about where to invest – manufacture, bank deposits, stocks or bonds, precious metals, real estate, financial, currency or other speculations.

An enterprise is designed to make new products, search for markets and select the best technology, means of production and methods of its organization. It is, in essence, a producer of commodities. The goal of business is to preserve the value of money by receiving passive income – interest, discount, rent, etc. This type of economic activity is passive in that it only reacts to changes in prices, profits and value of capital all of which are secured primarily through entrepreneurial activity.

An entrepreneur is not afraid to take risks. He does not even give thought to risk when he starts a business. In contrast, financiers shun risks, because they do not know all the capabilities of enterprises and markets; they cannot be sure what a particular government will do or how key financial markets will change. Even in these conditions they have to meet their commitments before investors.

They are mediators with interest in financial stability and predictability. Of course, financial profiteers earn precisely on “risks” – they like instability and abrupt currency and price fluctuations which enable them to buy lower and sell higher. Entrepreneurs are interested in innovations and their implementation, while financiers are very cautious about innovations. They would rather wait until a new thing is fully implemented and guarantees stable positive results. Investing financiers spread, rather than introduce, innovations.

Entrepreneurs need free access to resources and markets, laissez-faire and independence from the state, land owners, trade unions and creditors. In contrast, financiers are not interested in freedom and resources. They are ready to cooperate with the authorities, land owners, or anyone for that matter, in order to reduce risks and share them with others. This is why bankers, exchange brokers and investors do not, quite unlike entrepreneurs, seek political freedom and instead try to find ways to cooperate with the existing government regardless of how corrupt or totalitarian it may be.

In the USSR, there were no entrepreneurs or profit-oriented private investments. The economy was deprived of an ability to generate profits by cutting production costs and offering new consumer values on the market. In socialist times, the Ukrainian community reverted to a social system in which the economy was unable to self-improve, obtain entrepreneurial profits and efficiently use them, while Soviet society was incapable of cultural and intellectual growth.

IS THE PROFIT-ORIENTED ENTREPRENEURIAL ECONOMY WORKING TODAY? IF NOT, WHY NOT?

Several prerequisites must be in place for a profit-oriented entrepreneurial economy to function. First, prices must not be set on an individual basis. Instead, an average price should result from the interaction of all sellers and buyers of a certain product on the market. This price correlates with average costs in the industry and goes up or down depending on the supply/demand ratio. This is market, rather than administrative, pricing at work. In this case, price is an external factor for a specific enterprise and a common quantity for every player, independent of individual costs.

Second, entrepreneurial profit emerges only in companies that outperform others by installing newer or more productive equipment, using better or cheaper materials or organizing the production and administrative processes more efficiently.

Another source of profit is pricing: when an entrepreneur first comes out on the market with a fundamentally new product, he sets a price that is much higher than that of traditional products.

The same thing happens when a businessman opens new markets for his traditional products. Other entrepreneurs who have not achieved similar results incur production and marketing costs that are on the level of market prices or higher, and thus their activity does not bring that much profit.

In this case, entrepreneurs are content with bonuses for special managerial functions (formulating the overall conception, finding markets, landing large contracts, involving highly qualified CEOs, etc.) or receive rent payments as owners of land, minerals, buildings, communications and so on. The corresponding expenditures are, of course, part of production cost. Entrepreneurial profit is only one part of all profits received by company owners, so when it disappears, other components remain.

Third, entrepreneurship as a special type of human activity has a special existential niche. It brings together components of the manufacturing process and marketing procedure and secures the operation of a company established for this purpose. Success depends on how well the components are made to fit together, as well as the choice of equipment, labour and technology.

Entrepreneurial activity is also special in that it involves a constant search for new businesses and technologies; other (better) use of old equipment, buildings and land; closing old unprofitable companies and creating new ones in terms of the manufactured product, branch of industry and method of production. All these changes are innovative.

A true entrepreneur lives by innovating. Innovations are what enables businesses to put products on the market whose value greatly exceeds that of similar products made by other suppliers. Products of this kind bring the owner temporary entrepreneurial superprofits. (This highly important conclusion was first formulated by Joseph Schumpeter who once taught at the University of Czernowitz and served as the Austrian Minister of Finance.)

Those who fail to constantly innovate lose the initiative and zeal and soon stop being entrepreneurs as such, because their business loses its competitive edge, becomes unprofitable and eventually goes bankrupt or is closed.

Fourth, the entrepreneur is not, for all intents and purposes, a creditor, investor or financial partner. A person who seeks to accumulate and save money, receive interest on capital and make successful temporary investments never turns into an entrepreneur. He is a financier. The goal of an investing financier is to reduce the risks of capital placement (if possible), diversify investments, pull out of unsuccessful investments in good time and move his money elsewhere. A person who has accrued savings is primarily interested in investing in property, stocks, land and whatever else might secure the highest interest, dividend or rent.

None of the above pertains to the entrepreneur. His task is to organize and improve a specific business. Thus, if he has to also search for money needed to implement his business idea, solve tasks to minimize investment risks, etc., it will only hamper him and will hurt the economy in general.

Therefore, it can be concluded that financial business has to be a separate and specialized sector. Entrepreneurship cannot develop and be successful if the economy does not have favourable conditions allowing easy access to credit and investment market resources.

Fifth, anyone can become an entrepreneur, but he must have an intellectual, businesslike, socially and politically independent personality. This enables a businessman to carry out an objective financial analysis of existing production facilities, do marketing research, select the best new ideas in terms of design, technology and production and invite highly qualified specialists.

This kind of freedom is impossible in an unfree, closed, undemocratic, utterly bureaucratic and corrupt society. It also follows from this that a government employee, a law enforcement officer, a serviceman, a tax inspector, etc. cannot be an entrepreneur. Where people like that do “business” social goods are embezzled, bribery is forced upon citizens and criminally punishable abuse of office is rampant. Moreover, if an enterprise is launched and controlled by bureaucrats who cannot possibly have entrepreneurial qualities, it will not bring profits. In other words, n most cases it is impossible to adjust Soviet enterprises to a competitive market economy.

Sixth, a profit-driven entrepreneurial economy requires a competitive environment and a free market. The entrepreneur has to seek profits that arise from new combinations and improved business. If he is a monopolistic supplier of a special product on a certain market, he will objectively be able to set a much higher price compared to products in the same group on the same market. This price will reflect the real value and will include entrepreneurial profit as payment for innovation. However, a monopoly on innovation is short-lived in conditions of a competitive market economy.

Other producers also desire to receive innovation-generated profits and will try to start producing the unique product themselves as soon as possible. The growing supply will meet the spiking demand, and a monopolistically high price will go down. In this way, the price will begin to reflect production costs. Thus, competition destroys innovation-generated superprofits, and this is a positive phenomenon. The initial monopolistic supplier will be forced to come up with new types of products.

In other words, the entrepreneurial function would not be performed without competition, and a monopolistic supplier of a certain good would be content to receive stable superhigh profits and, instead of generating new business ideas, he would abuse his position by independently hiking prices, reducing the product’s quality, misreporting his profits, etc. So the entrepreneur himself is not idealist. He wants to maintain his monopolistic position as long as possible and tries to eliminate competition.

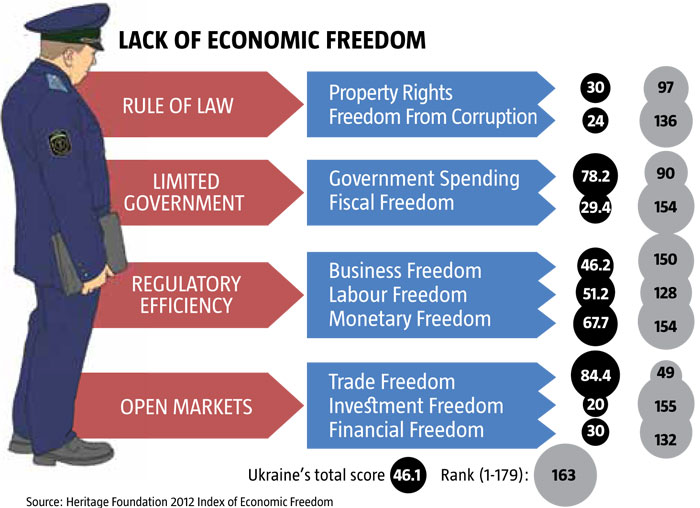

Artificially created and natural monopolies and their protection under the government, which was part and parcel of the socialist economy (and could not be otherwise because the state, as the sole owner, also craved for monopolistic superprofits) and survives, to an extent, in the current Ukrainian realities. However, the above suggests that this is a road to degradation. Moreover, entrepreneurial activity alone – without the government's involvement to support competition and overcome monopolism – may fail to produce positive social results and may, to the contrary, lead to economically unacceptable business structures and skewing the market.

Seventh, society must work out a tolerant and reverent attitude to entrepreneurs, both at the everyday and state level. This is the starting point for the mental and physical attitude of government officials, tax inspectors and policemen to businessman as a social group and to entrepreneurial expenditures and profits (including superprofits). If these financial resources that entrepreneurs have are viewed as undeserved, unfair and earned at the cost of “exploiting the working class”, taxes will be superhigh; policemen and inspectors will be unduly biased; and the investment and business climate will be unfavourable.

Social acceptance and intolerance have to be based on the understanding that entrepreneurial profit originates from labour. In contrast, monopolistic superprofits and corrupt political rent generated by certain businessmen must become a target of social obstruction and punitive persecution on the part of government, law enforcement and judicial bodies. Therefore, it is important to discriminate socially useful types of profits, such as entrepreneurial and innovation-based profits, and harmful and illegal profits (resulting from monopolies, corruption, profiteering, etc.) and stimulate companies to focus on the former. This may not be an easy thing to do, because profits, just like money, do not smell.

UKRAINE AS A CAGE FOR ENTREPRENEURS

Does Ukraine possess the above features and meet the requirements set for a profit-oriented entrepreneurial economy? A hostile attitude to private entrepreneurs – independent, innovative and creative – is undisguised and widespread in Ukraine. The public has formed an image of in impudent and greedy fraudster. Most people perceive the state as the sole benefactor that guarantees justice and develops the manufacturing industry. Mentally, Ukrainian society tolerates entrepreneurs as the unnecessary addition to the freedoms and property rights enjoyed by the citizens. Tax inspectors and policemen have been set on entrepreneurs like hounds. Fiscal pressure has cut off energy supplies to entrepreneurs.

Only those who cooperate with officials and those who have billions command respect because they can nicely reward a judge or a journalist. Entrepreneurs are not being raised or educated in Ukraine. Specialized colleges and institutes equip students with technological expertise and knowledge of economic relations in their respective industry (manufacture, construction, transport, commerce, tourism, the restaurant and hotel business, design, etc.) but not with the skills needed for entrepreneurial activity. Neither are individual approaches or nonstandard solutions encouraged. Thus, it should not come as a surprise that college graduates look for jobs only in existing organizations and fail to find them. They do not even think about starting their own business.

Our country lacks the cult of inviolability of a private individual and the protection of personal information. The rights and freedoms of people are not a supreme value like in the Western world.

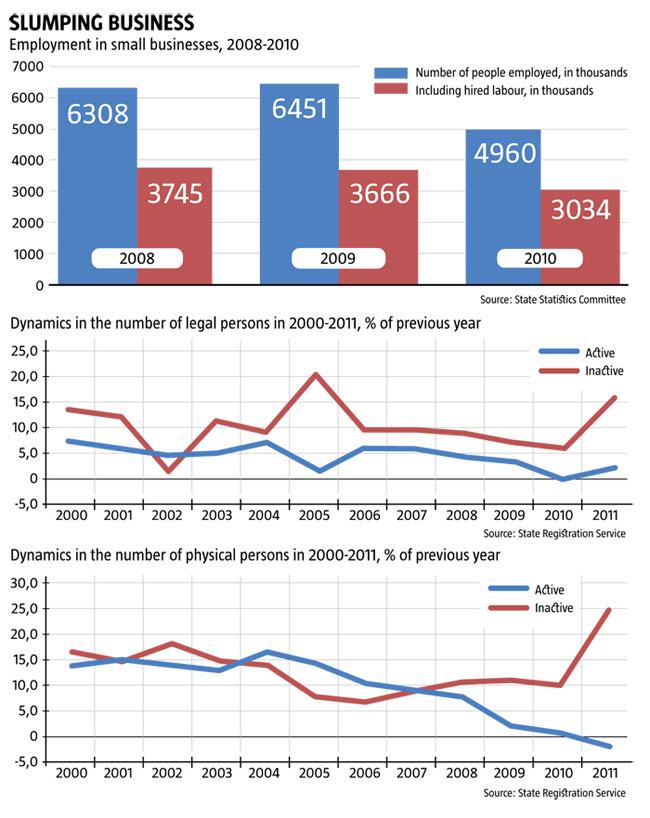

The entrepreneurial sector in Ukraine is very narrow, sparse and marginal. The authorities view it as a place for small-scale flee market transactions and related industries (delivery, transport and financial services). The entire system of financial and legal relationships between the authorities and entrepreneurs is built on this foundation.

It is still “permissible” to engage in individual activities that involve providing various intellectual and other professional services. There are few other sectors where entrepreneurial zeal can be seen: residential construction and business property development, entertainment centres, resorts, shopping malls, etc.

Due to destructive privatization and government-backed elimination of competition, the new owners of industrial, communications and agricultural enterprises inherited by Ukraine from the USSR never turned into entrepreneurs. They are content to receive other types of net profits – corrupt and monopolistic profits, various subsidies and soft loans, rent on mineral mines and fertile land, etc. Thus, most of them continue to lose their markets and revenue.

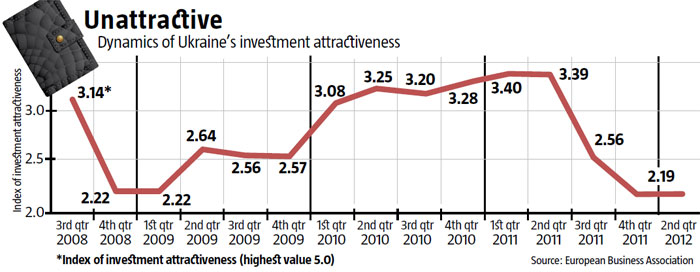

Unfortunately, entrepreneurs are unable to obtain sufficient financial means to develop production. The state is of no help, not even in R&D and socially significant projects. Instead, it sets tax traps to freeze revenue and confiscate property. Moreover, since Ukraine became independent in 1991, sky-high bank interest rates have made bank loans unaffordable. Bank loans do not account for even one-tenth of the demand in the national economy. The annual increase in credit resources has been at a mere UAH 60-70 billion in the past several years, which is less than five per cent of Ukraine’s GDP.

But independent entrepreneurs have received virtually none of this money – it is distributed among those who are close to the government, own financials institutions and who are not entrepreneurs by definition. When resources are lacking, there is no sense to seek innovations, manufacture new products and build the necessary equipment. That is the reason why there are no Ukrainian-made innovative goods to be seen.

The entrepreneurial sector accounts for an unacceptably low part of the national economy and is mostly marginal, which hampers the profitability and progress of Ukraine’s economy. An extremely heavy burden is placed on the national economy by unprofitable companies – at least 45 per cent of the total number in some years and 56 per cent during the crisis in 2009. This means that true entrepreneurs did not have access to such companies. It is also worth noting that the lion’s share of profits is secured by the financial and credit sector of the economy. Approximately one-third of enterprises in the industrial sector make any profit, and of these no more than 10 per cent are entrepreneurial, according to my calculations.

Another roadblock is the non-market character of Ukraine's economy: prices are set by the authorities, certain commodities are regulated in an administrative fashion; the central government interferes with the distribution of financial resources; the government puts restraints on foreign economic activity and so on. Therefore, Ukraine has found itself in an impasse — there is no future without entrepreneurship.