Jean-Claude Marcadé, a notable French art critic and museum curator, believes that the complexities involved in the process of understanding 20th-century Ukrainian avant-garde art as a distinct phenomenon prevent it from assuming its rightful place in the worldwide cultural scene.

According to Marcadé, information about Ukrainian culture is often perceived through a Russian lens at the international level. However, the French scholar is making efforts to change this situation.

U.W.: What is the foundation for your claim that Kazimir Malevich was a Ukrainian painter?

I wrote and published the first monograph about him in 1990. Earlier, there were problems with dating some of his works and life events, so I had to reconstruct his artistic evolution. Moreover, I was the first to speak about his Ukrainianness. It is not necessarily about ethnic origin—for example, art critic Dmytro Horbachov believes that Malevich’s mother was Ukrainian. This world-renowned painter matured absorbing Ukrainian geography, Ukrainian culture, Ukrainian landscapes and the Ukrainian colour palette, which is, I assure you, much more important than ethnic background or religion. However, we should not forget how Malevich realized himself in Russia and in the West, so he is not at all a 100-per cent Ukrainian painter.

In the late 1920s, upon returning to the Soviet Union after his period of suprematism, he experienced a kind of “re-Ukrainization”. He came to Ukraine and fit into the Ukrainian artistic context of the time. He contributed to the Nova heneratsiia [New Generation] journal and, with his purity and energy of colours, became a kind of a third party in the relations between Mykhailo Boichuk’s followers and spectralists. Incidentally, he criticized the former for their imitative tendencies, saying that they put Byzantine-era clothes on collective farm workers and made replicas of icons. This is despite the fact that he himself imitated icons in the images of peasants based on iconic prototypes. I believe that his special colour palette was largely borrowed from icon painting.

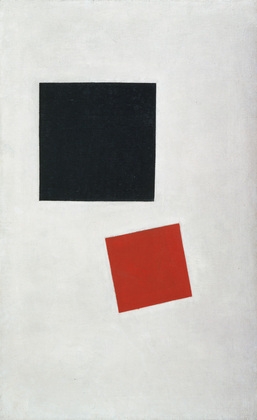

“Boy with a Knapsack”

U.W.: To what extent is the concept of a Ukrainian avant-garde accepted in the West?

The notion of Ukrainian historical avant-garde that existed in the first quarter of the 20th century as a self-sufficient phenomenon, rather than as part of a Russian movement, is becoming established in the West with great difficulty. People are only now becoming used to it. There are those who are fighting to have it recognized. I am happy I am not alone in this group, but things like this take time. Virtually no Russian art critic agrees with this approach.

READ ALSO: The Art of Resistance

U.W.: What made the “Ukrainian avant-garde” stand out?

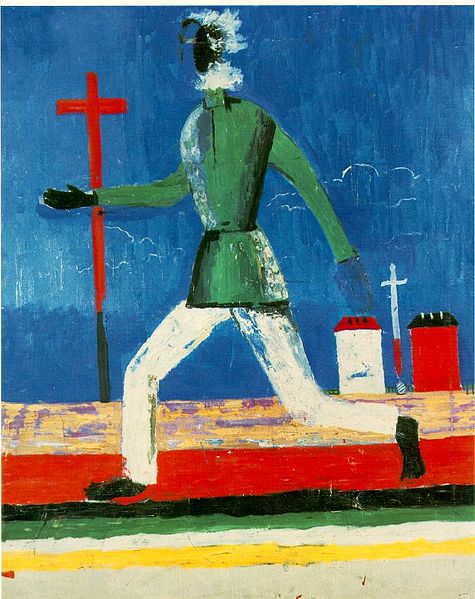

Avant-garde is, in general, an international phenomenon. However, the Ukrainian avant-garde had certain distinct features of its own. First, it had special colours. Take only the role of yellow in the works of Ukrainian artists at the time: it was the saturated colour of the sun… Second, there was a special experience of space. The steppe must have played a special part in the history of Ukraine: this kind of vast “steppe-like” space is very typical of Ukrainian avant-garde painters. Hence the spirit of freedom. And, of course, there was special mirth and humour. Take, for example, Malevich’s painting “Boy with a Knapsack” (at the New York Museum of Modern Art): two squares, one bigger than the other. Or take his “Reservist of the First Division”… At the same time, Malevich knew how to be serious and tragic. His late works, such as “Peasant Between a Cross and a Sword” or the famous image of a peasant woman with a black face (which can be understood as a coffin) may be viewed as an interpretation of the tragedy of the 1930s. It is an extremely universal and symbolic interpretation, and it is hard to find any analogue in the art of that period. At the same time, we need to bear in mind that this is not the only possible understanding of such works.

“Reservist of the First Division”

U.W.: In your opinion, why did 20th-century avant-garde artists sympathize with totalitarianism so often?

I have often thought about this. In the former Russian Empire, they hoped that a new life would come, the old sores of “bourgeois culture” would disappear and that a revolution would wash away all the evil of the world like a flood. They perceived revolution as the youth of the planet and as an opportunity to create freely… However, they soon became victims of the revolution they had welcomed. Thus, the concept of totalitarianism was not as prominent in people’s consciousness back then as it is for us today. The situation in the West was also different: people often had an aesthetic, rather than realistic, attitude to politics.

In any case, it was evident that this sympathy was not reciprocal: 20th-century totalitarian regimes did not particularly like the avant-garde and destroyed it when they had the chance.

READ ALSO: The Painted Garden

U.W.: What are the relations between the historical avant-garde and contemporary art? Is there continuity or they at odds with each other?

Tentatively speaking, the historical avant-garde was opposed to the Itinerant Movement in that it wanted to return to the essence, foundation and prototypes of art. It was as if avant-garde art was saying “art is not literature, or description, or a plain history of sociopolitical nature”. According to avant-garde reasoning, revolutionary art is not about depicting revolutionaries but about turning the consciousness of the observer upside down and offering an absolutely unexpected view on things. Because art evolves in cycles and it is impossible for it to remain attached to its abstract essence forever, we are now going through a different phase: contemporary art is again drawing closer to literature. It is trying to narrate, be understandable and social and reach out to the public at large. Hence the tendency to use long summaries and explanations. People want things to talk, and this is a perennial problem. Thus, we now have a “new Itinerant Movement”, although in a completely different form. I believe that this too will pass and we will see a new phase. We also need to remember something else: many of the works that are very prominent today will not maintain this status in the future. I recently read Guillaume Apollinaire’s reviews, and I should say that most of them are about works and authors that are clearly secondary and little known today.

“Peasant Between a Cross and a Sword”

U.W.: In your opinion, what needs to be done to help the global community learn more about the achievements of the 20th-century Ukrainian avant-garde?

Ukraine – its society and state – must make efforts to popularize the heritage of its 20th-century avant-garde. It is very poorly known. Apart from a group of recognized top-class figures (Malevich, Aleksandra Exter, Alexander Archipenko, Oleksander Bohomazov, the Burliuk brothers, Mykhailo Larionov and a few others), Westerners have hardly heard about anyone else. Moreover, they fail to distinguish them from Russian artists. (When a retrospective show of Bohomazov’s works was held in Toulouse several years ago, the press used attributes like a “Russian cubo-futurist”). Exhibitions need to be held to actively attract attention, because in Paris, for example, countless artistic events take place at the same time. Some things are being done, but it is clearly not enough so far. Here is a telling fact about awareness of Ukraine and its art. Some 10 years ago, a Moscow correspondent of a French newspaper (they did not and still do not have special correspondents based in Kyiv and receive all their information through a Russian prism) wrote about Ukraine and mentioned a “novelist Chevchenko”. Promotion of Ukraine is not something that only Ukraine’s friends in the West should be asked to do. Rather, the country itself needs to actively contribute to the promotional effort. I recently wanted to prepare a special Ukrainian edition of a respectable journal of Slavic studies, but I found that it was very hard to get Ukrainians to contribute papers. Everyone said “yes” but few actually submitted articles.

READ ALSO: Touching the Nerve of Time

U.W.: What do you like about modern Ukrainian art?

I am better acquainted with the works of the older generation. I like the pure art of Tiberiy Szilvashi and Anatoliy Kryvolap’s “figurative abstractions”. Then there is Oleksandr Dubovyk, who seems to be underestimated in Ukraine. In addition, Volodymyr Kostyrko has interesting combinations of epochs and cultures.

BIO:

Jean-Claude Marcadé is one of the world’s most authoritative researchers of avant-garde art. He holds a doctorate degree in literary studies and is the emeritus research director of the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS) and the president of the “Friends of Antoine Pevsner” association. Marcadé has curated art exhibitions in Paris, Berlin, Madrid, Barcelona, Bordeaux, Saint Petersberg and other cities. He is the author of Malévitch (1990), Calder (1996), Sergueï Eisenstein. Dessins secrets (1998), Anna Staritsky (2000) and Nicolas de Staël. Dessins et peintures (2009). A Ukrainian translation of Malévitch was published in 2013.