The Ministry of Justice reports that at the beginning of 2013, Ukraine had over 15,000 officially registered charity organizations and foundations. This is a lot, but quantity does not mean quality. In a 2012 study of private charity development in the world by the Charities Aid Foundation, Ukraine landed 111th, dropping six points from 2011. Sociologists have determined a persistent mistrust and a general lack of understanding of the point of charity in Ukrainian society, especially among people aged over 35. This attitude is made worse by the alert attitude of government authorities to corrupt charity initiatives schemes that they are not involved in and tax pressure. The new Law “On Charity Activities and Charity Organizations” enacted in February 2013 has failed to solve key problems in this sphere.

INERTNESS AND DISTRUST

“Up to 2,000 new charity organizations have emerged in Ukraine annually in the past few years,” says Anna Hulevska-Chernysh, Director of the Ukrainian Forum of Philanthropists. “This surge is not surprising. It coincided with many election campaigns where politicians tried to buy voter support with philanthropy. This is why only 2,000 or 15% of the 15,000 officially registered charities actually work in Ukraine.” According to the Ukrainian Forum of Philanthropists, all EU member-states have 110,000 officially registered charity organizations. Compared to their rate of one charity organization per 4,500 people, Ukraine’s one per 3,000 looks inspiring. However, a survey conducted in 2012 by the Democratic Initiatives Foundation and the Razumkov Centre, confirmed that most charities in Ukraine only exist on paper: only 21% of Ukrainians supported them last year, only 6% did so because they trusted them.

The poverty of Ukrainian society is commonly considered to be the main cause of the reluctance to donate to charity. However, welfare is by far not the key factor in philanthropy. International surveys prove that it is much more common and efficient in some countries that are poorer than Ukraine. This attitude stems from the Soviet past, says psychologist Nadia Artyshko. “The Soviet government kept telling people that there were no such things as problems in the USSR. Plus, it fought against the church, where charity was one of the basic elements, and stifled any private initiative in people, even philanthropic. Add to this the Soviet “preventive” struggle against beggars, and the discouraging experience with many fraudsters begging for money today,” she explains.

CHARITY FRAUD

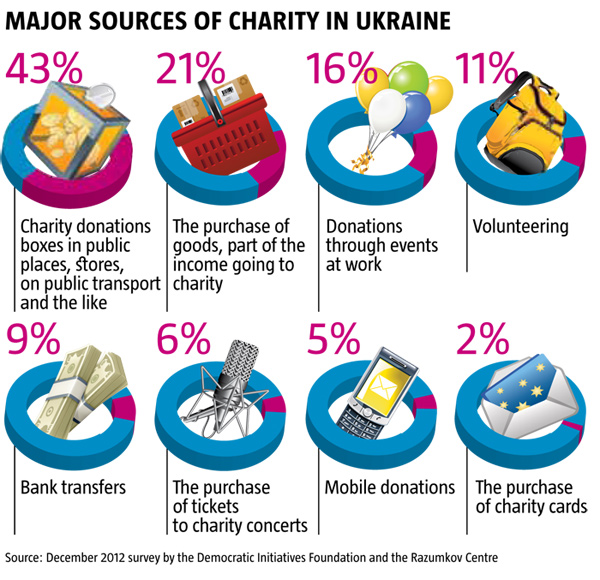

Based on the above-mentioned survey by the Democratic Initiatives Foundation, the key charity instruments in Ukraine include contributions through charity boxes (43%), the purchase of goods where part of the income is donated to charity (21%), and participation in charity events organized by employers (16%). These are the methods most often used by fraudsters.

Most fraudsters ask for money in public transport. In Kyiv, the subway is the most popular venue. They normally ask people to help them buy a train ticket home, pay for a surgery for a family member, and the like. Most have some kind of certificate, ostensibly confirming the diagnosis. However, police statistics claims that up to 95% of them are fraudsters.

“Fraudsters went from door to door, telling people that a sick girl needs treatment in Germany,” volunteer Oleksiy Savka says of a recent fraud discovered by a Kyiv-based charity organization. “They said that the state wouldn’t help the girl, so they had to collect the money from the public. They were only exposed two months later, but the police refused to charge them. That’s the reality. No wonder people often treat charity volunteers like sales agents.”

“I once decided to help a sick child,” says Oleksandr Troshkin, a manager at an international company in Kyiv. “There was a large plastic box with the baby’s photo and a plea to help the parents pay for treatment abroad. Below was a contact number. As I had read about the latest news on charity frauds, I called the number to ask how the baby was doing. No-one answered. I later discovered that this was a scam that brought the people behind it over UAH 200,000. Now, I treat charity organizations with caution.”

“Unfortunately, the number of charity fraudsters is growing,” says Dmytro Struk, President of the Sertse do Sertsia (Heart to Heart) Foundation. And they have been using new ways to get money. “They call commercial companies and ask for permission to collect money for a charity cause,” Serhiy, an investigator in Kyiv, shares. “Or they propose that companies support a charity event, preferably a one-time one. According to our statistics, up to 40% of all frauds are done this way because it’s fairly easy. If the fraudsters manage to fool the company, the latter collect money from their employees or the company pays for the cause from its budget. The amounts they earn this way are much higher than those they collect on the streets. The risk is higher, of course, but the fraudsters have become skilled in this art, and make authentic-looking fake documents.”

Experts believe that an important step in changing this would be to switch from cash donations to non-cash bank transfers. However, this will not eliminate charity fraud altogether. Serhiy and Oksana Frolov experienced one eighteen months ago when their nine-year old son was diagnosed with thyroid cancer. The couple opened an account at one of the largest banks in Ukraine. “Thanks to our friends who work on TV and helped us air our appeal for help on many channels, we received a goodly sum,” Serhiy says. “But fraudsters gained access to the account because of staff negligence, or so we were told by bank employees, and stole all the money, nearly USD 5,000.”

THE GREEDY STATE

The new law has made it much easier to register a charity organization or foundation in Ukraine. Even a group of individuals with a founding act and a charter listing their goals and expected sources of income, will almost surely get a registration at the Justice Ministry. At year-end, they are obliged to disclose financial statements, have independent supervisory boards and report to the tax inspection. Experts claim, however, that 90% of all existing charity organizations ignore these requirements.

“There are barely any charity statistics in Ukraine,” claims Anna Hulevska-Chernysh. “On the one hand, the state, represented by the tax authority, is not providing this information. If published, it will reveal that charity is subject to taxation in Ukraine, which is nonsense in most other countries. On the other hand, most charity organizations do not disclose their financial statements. The huge tax pressure urges those willing to donate to do so unofficially, while companies record their donations to charity as marketing or PR expenses rather than charity expenses which can account for 1-4% of their total budget. Under the current Tax Code, donors have to pay income tax on aid to recipients.” And banks rarely warn people opening a charity account that current legislation does not classify incoming funds as special-purpose funding, thus they are subject to taxation, plus bank fees.

This burden virtually stifles the development of some popular and effective charity technologies that are used all over the world, such as mobile donations. Mobile operators in Ukraine say that any text message, even if it is sent as a charity donation, is subject to a 20% VAT and 7.5% Pension Fund fee. As a result, the recipient gets 45 kopiykas at most from a charity text message costing UAH 1.

In addition to the tax burden, another big problem is the misappropriation of charity funds. In the recent past, state institutions including hospitals, orphanages and social services, would often sell the medicines, humanitarian aid and equipment sent to them as aid. This bitter experience has now taught charity organizations to try to supervise them more closely. As a result, many recipients often refuse to work with donors. Social services boycott most private charity initiatives because this blocks the traditional corrupt scams used for embezzling funds allocated for social aid and work. “Our state authorities, with only a few rare exceptions, don’t like charity organizations, because they can provoke inspections or turn media attention to the misappropriation of funds, while striking a bargain with charity organizations is more difficult than with inspection authorities, because the former are mostly driven by enthusiasts,” says volunteer Andriy Vlasianets. “In fact, whenever it comes to private initiatives, the government immediately sees this as a threat to itself, some sort of politics. Therefore, the best thing would be for government authorities not to interfere, issue all necessary licenses and keep tax inspections to a minimum. Lately, tax authorities have been visiting efficient charity organizations, especially international ones, on a regular basis.”

Five steps to avoid charity fraudsters

1. Check the official registration of the charity organization or foundation asking for your donation at the Justice Ministry

2. Demand charity organization’s portfolio, i.e. information on earlier campaigns conducted by the organizations, preferably with financial reports on expenditures and the use of the funds they collected.

3. If you or your company decides to donate funds to a charity, the best option is to do it via transfer through a reliable bank, preferably an international one.

4. Demand a report detailing what the organization is planning to spend the donations on, and a final report, before donating money.

5. Remember that the new law on charity passed in February 2013 allows you to demand the reimbursement of your donation if it was misused by the charity.