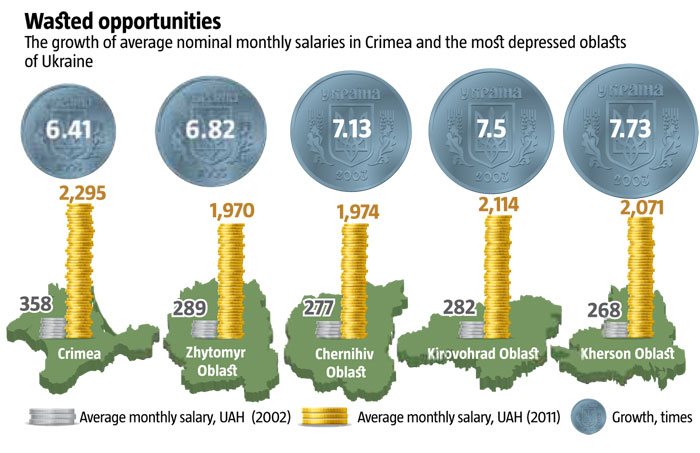

In 2011, Crimea’s annual per capita income was just UAH 17,600 or $2,200. Despite its huge tourism potential, Crimea lags behind the traditionally depressed Kirovohrad, Zhytomyr and Chernihiv Oblasts, where annual per capita income ranges from UAH 17,700 to UAH 18,700 or $2,210 to $2,300.

Over the past decade, average monthly salaries in Crimea have grown at a pace slower than all of the abovementioned regions of Ukraine. Twenty years of Crimean autonomy as part of independent Ukraine show that it has failed to make the best of its unique natural, climate, cultural, historical, transport and geographic potential in a constructive and creative way. Crimea was sacrificed to the destructive idea of cementing a soviet reserve in the peninsula, building a bastion of resistance to Ukraine’s European and NATO integration and to the consolidation of the political Ukrainian nation. It now acts as a platform for radical Moscow-oriented anti-Ukrainian and neo-imperialistic organizations. The phantom lament of the “glorious soviet past”, manipulated to serve the ambitions of would-be regional elites, has hampered Crimea’s prospects of becoming a multi-ethnic resort, shipment and communications centre of international scale. Meanwhile, various tactics have been employed to keep the peninsula in a constant state of tension and stress, such as the notorious recent media wars and speculations of possible ethnic clashes used to discourage potential tourists.

FOREIGN PRIORITIES

Local elites (and the population’s ability to select them) play a key role in Crimea’s relations with the centre and the freeing of its potential. When the elite has priorities alien to the territory and the population it purports to represent, the whole region falls hostage to it. That is exactly what has happened in Crimea. Unlike the elites of Donetsk and Western Ukraine, Crimea’s crème de la crème were ultimately unprepared to promote and protect regional interests on a national scale. Instead of integrating with the Ukrainian political sphere, they pursued their own autonomy and looked to Moscow or a balance between the Kremlin and Bankova St.[1] They were eventually pushed to the sidelines after the Donetsk group came to power and occupied Crimea, beginning with the appointment of the late Vasyl Dzharty as Chair of the Crimean Cabinet of Ministers. He brought along a huge team of new managers of various levels. This has continued under his successor Anatoliy Mohyliov. As a result, people born in Donbas or nearby oblasts ended up in all the key offices of government and law enforcement authorities in Crimea.

Over the past 20 years, Crimea’s governing elite has shunned outside investment, preventing the growth necessary to create a modern resort infrastructure. Meanwhile, the lion’s share of revenues from existing tourism remains in the shadows. It enriches semi-criminal entities and the officials who assist them in exchange for kickbacks. At one point, the Crimean government declared the introduction of a tourism tax that would earn the local budget 6-7 million US dollars annually, an extremely low amount given Crimea’s real resort potential. This reflects the degree to which the region’s tourism business remains poorly developed and in the shadows.

Comparison to other Black Sea and Balkan resorts reveals that the most successful ones adjusted their services and price-to-quality ratio to meet international standards. Crimea has not yet done this. Most tourists come to Crimea from Russia and the FSU because they find it more affordable than the Russian Caucasus Black Sea coast, and more familiar in terms of mentality compared to more developed tourist destinations abroad. Moreover, Crimea has failed to become a year-round resort. This is only possible with the proper investment policy. Compared to the successes of Turkey and Georgia in winning over the tourist resort market, Crimea looks like an isolated island, obsolete and poorly developed. Its focus on the unpretentious soviet-type contingent of tourists will continue to cement the peninsula’s obsolescence, while alienating it from the benefits of growing international tourism proceeds.

OCCUPIED KHERSONES

Another destructive factor is Crimea’s orientation toward the military and political presence of Russia and the extended rental of a slew of strategic objects to the Russian Black Sea Fleet. Sevastopol’s military status makes private non-Russian investors reluctant to invest in the development of non-recreation infrastructure—transportation foremost—let alone tourism.

Under the current deals with Russia, Sevastopol suffers great losses due to the location of the Black Sea Fleet on its coast. First and foremost, the Budget Code allows Sevastopol to keep 100% of revenues from property and real estate taxes[2]. Obviously, in a city whose real estate is among the most expensive in Ukraine, property taxes represent a key to prosperity. The Russian Black Sea Fleet leases over 14,600 hectares of land, while the city of Sevastopol itself occupies 107,900 hectares. This means that if the local community obtained the land currently leased to the Black Sea Fleet, the rent would bring increased revenues amounting to tens of millions of hryvnia. The current base rental fee in Sevastopol is UAH 21,500 or approximately $2,680. If more land emerged on the market at prices far below market value, this would facilitate construction, upgrade of infrastructure, and job creation, and fill the city’s coffers in the future. According to estimates made before the Kharkiv deals were signed, the minimum benefit reaped during the first year following the departure of the Russian Black Sea Fleet would amount to an additional UAH 1.5bn for the local budget.

So far, Sevastopol enjoys two statuses: that of a city and a region. Therefore, it does not pay any taxes to a higher territorial administrative unit, and has potential to become a powerful transportation and tourist centre. In reality, it is essentially a closed military zone and a cold war remnant.

Essential changes for the sake of progress in Crimea and Sevastopol are only possible once the locals realize that their role of “military outposts” and “unsinkable aircraft carriers” does not fit into the current geopolitical reality and their future lies in a focus on European values and Ukraine’s European integration. Crimeans will only succeed in freeing their region’s potential and avoiding ethnic and political clashes by overcoming the remnants of the Soviet Union and opting for a more promising model of development. In order to do this, Crimea will have to re-evaluate its current priority of remaining an enclave of the ephemeral “Russian World”.