Not long ago, I was taking a walk with my son in our home town, Dnipropetrovsk, when we came ran into an interesting 80-year-old woman who reacted with happy surprise that a five-year-old child could speak Ukrainian so well.

“People used to be ashamed to speak Ukrainian,” she explained. “Now it’s normal. Now they speak Ukrainian on TV and on the radio. Of course, I write better in Russian. Ukrainian’s a bit hard for me.”

“I guess you were taught in Russian at school,” I ventured, “and all your documentation at work was in Russian.” I definitely wanted to keep this conversation going.

It turned out she was the native daughter of the kozak settlement of Obukhivka in Dnipropetrovsk county and was eager to talk about her life. She complained, too, that her grandchildren spoke more in Russian, just like her children.

RELATED ARTICLE: Why the Bolsheviks needed the Holodomor

“Well, Ukrainian was always considered second class. You know, a photo correspondent friend of mine tells me that in the 1970s in Dnipropetrovsk, when people heard him speaking Ukrainian, some would start calling him a dirty bumpkin. The battle against ‘nationalism’ was ruthless…”

The minute she heard the word “nationalism,” the elderly woman went into defensive mode, trying to persuade me that Ukrainians should speak both their own language and Russian. And although I support the principle, “the more languages, the better,” I think that making English the second official language would offer far more opportunities for Ukraine. It became clear that the woman was trying to end our conversation. For a person who had grown up in soviet times, the subconscious terror of being accused of nationalism had not died.

The Holodomor effect

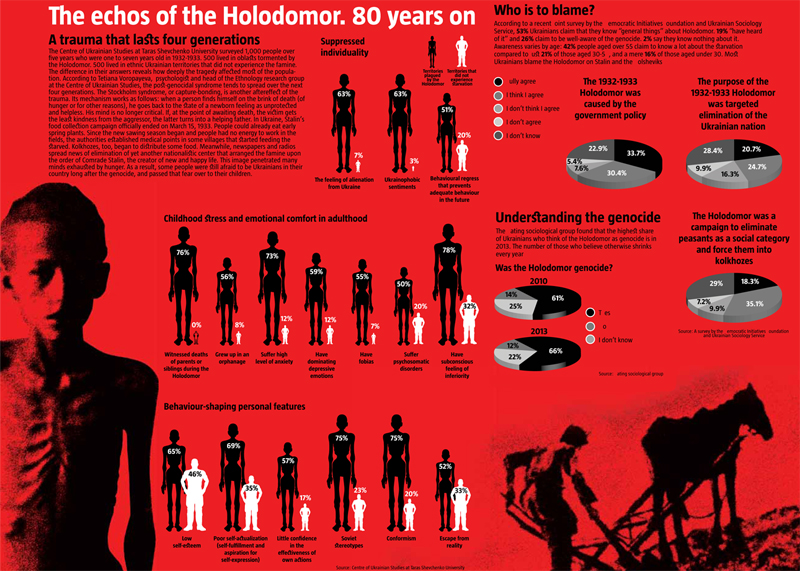

Over 2003-2008, researchers at the Ukrainian Studies Institute at Shevchenko National University in Kyiv carried out a study in which they polled 1,000 Ukrainians who had been between the age of 1 and 7 1932-33. Half of these people had spent their childhood on territories hit by the Holodomor, the other half in territories where there had been no famine. The results showed significant differences in personality traits between the two groups. Those who had suffered in the Holodomor were unable to defend themselves in confrontations, were less ambitious, suffered from low self-esteem, felt less happy with their lives, and they were likely to suffer from depression, phobias and psychosomatic illnesses. But what was the strangest was that victims of the Holodomor were less likely to consider themselves Ukrainians and patriots.

Feelings of “estrangement from Ukraine and its national interests” were evident in 63% of the respondents who had survived the Holodomor, and in 7% of those in the control group. What’s more, Ukrainophobic tendencies were almost as prevalent, at 63% in the main group and 3% in the control group. People who had survived the Holodomor were more likely to uphold soviet communist values such as “don’t stand out,” “be like all the others,” and “don’t be a nationalist,” and to believe in the ideals of “proletarian internationalism,” which seems quite contrary to common sense. Why did these victims not condemn their aggressor but, instead, follow his example?

RELATED ARTICLE: The echoes of the Famine in today's separatism in South-Eastern Ukraine

It appears that a special relationship is established between a victim and their aggressor. This phenomenon has been studied by Americans such as psychiatrist Frank Ochberg, psychologists Dee Graham, Edna Rollings and Robert Rigsby, Polish psychiatrist Antoni Kepinski and Swedish criminologists Nils Bejerot, who gave this symbiotic relationship the name that western European psychologists and American journalists picked up on: the Stockholm syndrome.

The name comes from an incident in Stockholm in which terrorists captured four bank employees and held them captive for several days while threatening to kill them. After being released, an unexpected phenomenon was observed: the victims announced that they were not afraid of their kidnappers who had “done nothing bad to them,” but the police. They hired a lawyer at their own expense to defend the two perpetrators and later befriended their families. This phenomenon, where a victim begins to like the aggressor or even to identify with him has since been called the “Stockholm syndrome.”

The FBI bulletin for 2007 reported on the results of more than 4,700 cases of hostage-taking. The Stockholm syndrome was evident in 27% of the victims, the rest of the American hostages proved resistant to the “charisma” of those who kidnapped them. The conclusion can be made that far from every individual is likely to become psychologically dependent on those who hold their life in their hands. A good deal depends on the determination of the person, and that depends very much on their previous life experiences: what kind of psychological trauma they have faced, especially in childhood; how mature they are; how capable they are of individual action and critical thinking, their physical condition, and the specific circumstances under which they were attacked.

Pre-soviet traumas in Ukrainian society

What do we know about earlier, pre-soviet trauma experienced by Ukrainian society? Some answers can be found by asking the director of the Alex Pol Institute for Economic and Social Studies, Volodymyr Panchenko, who is a specialist in economic history and a PhD in history.

“After the collapse of Kyivan Rus, a part of Ukraine’s territory continued to belong to a Ukrainian state under the Halych-Volynhian Principality for more than 200 years,” says Panchenko. “Then these lands became part of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and later still, part of the Polish kingdom. In the mid 17th century in the Dnipro Valley, the only state-like entity dominated by ethnic Ukrainians was Kozak Ukraine. There was neither nobility nor serfdom here, and kozak taxes on the farmers were not especially burdensome: they paid for the use of land and for protection against invaders.”

RELATED ARTICLE: The history of Ukraine's economy: from the 11th century till present days

After the Pereyaslav Council, tsarist Muscovy gradually expanded its territory to include the free kozaks. “Peter I instituted economic sanctions against Ukrainian merchants who had previously traded successfully with Poland, Germany and the Orient,” Panchenko goes on. “In 1701, he prohibited them from shipping a slew of Ukrainian-made goods to Baltic ports—at that time Riga, Danzig and Königsberg, today Gdansk and Kaliningrad. The only way Ukrainians could now export was through Archangelsk,[1] which was thousands of kilometers away, and to which it was only possible to travel in winter, when the extensive northern swamps were frozen over.”

At the same time, foreign-made stockings, gold and silver thread, expensive silk fabrics, sugar, paint, canvas, and tobacco could no longer be imported into Ukraine. “Russia had set up its own centralized factories to make such goods and all the markets were to be preserved for them,” Panchenko notes. “This caused Ukraine’s merchant class to be completely subordinated to Russia’s, which had direct access to cheap, quality imports and now began to act as the middleman—very similar to the 1970s and 1980s in the Soviet Union, when Ukrainians traveled to Leningrad and Moscow to buy good quality items and goods that were not available at home. The Russian-Ukrainian border now raised additional customs duties to fill the Tsar’s treasury… In fact, systematic redistribution from Ukraine’s budget to Russia began already here, but there was no gas transit system yet and it was a lot harder to control Ukrainians back then.”

Nor were Ukraine’s farmers and peasants spared. “The fact that their ancestors had lived for an age on specific territories made no difference if the Polish lord, during Polish rule, or a Russian official, after the destruction of the Zaporizhzhian Sich, decided that some parcel of land appealed to him,” says Panchenko. “‘Where are the documents that prove that this is your land?’ What documents could the kozak or farmer have, if freehold law had ruled since hundreds of years: whoever first settled a spot and paid taxes was the owner? Farmers began to lose their land and became peasants, while under Catherine II, they were turned into serfs. They had lived for hundreds of years without the support of a national state, without anyone to guarantee their rights and freedoms, and the only way to have a ‘career’ was through vassalry. None of this fostered the development of a stable national identity.”

Four steps to self-hatred

The Stockholm syndrome is fostered by the same conditions as the brainwashing technologies favored by totalitarian sects. It starts with controlling access to information. On one hand, the victim becomes isolated from contact with other religious students and those with different views, even family and friends until such time as the victim has “strengthened in the faith.” On the other hand, concepts are imposed on the victim. Victims are the most receptive to the “right” information when they are in an altered state of mind: either they are afraid—say, of demons, tempters, death, the coming of the Apocalypse, or punishment for sins—, or are prevented from satisfying their basic needs: exhausting fasts, sleep deprivation through all-night prayer vigils, torture as ‘penance for sins,’ and forced sexual abstinence.

During the Holodomor years, a great swath of the population was in a state of restricted awareness because their bodies were exhausted and they were subject to physical agoniesdue to famine: swollen guts and extremities, splitting and cracking skin, stomach acid consuming internal organs, and so on. The only thing people in the countryside could think of under these circumstances was food, yet any information related to produce—about “nests of nationalists” in the farm sector or about “kurkuls” who were hiding bread, aroused their interest. Those who were on the edge of starvation had no spiritual strength left to connect these ideological “transfusions” with the bizarre events taking place in their own lives.

One of the key factors to bringing out the Stockholm syndrome is the victim’s hope for an opportunity to negotiate with their aggressor, to find a point of compromise with them. “A person who receives goodness from someone they expected to get evil from feels more obligated to their ‘benefactor,’” Niccolo Machiavelli once observed. If a wrongdoer suddenly shows a drop of goodness—gives you a glass of water and doesn’t shoot when he promised to kill you—, this deed takes on immense proportions in the mind of the victim and becomes a straw that they very much want to grasp. A small kindness from an aggressor when your life is in that person’s hands is accepted with excessive gratitude because it offers the hope of survival.

The psychodynamic of how victims absorb the “logic” of their aggressors looks like this. When they get a signal in the form of a “small kindness,” the victim begins to focus on the positive features of their torturer and attempt to understand their system of values and needs. When the person’s life is in danger, the impulse to do so is enormous and fear limits the person’s capacity for rational assessment. And so the transfusion of foreign values takes place very quickly, without critical evaluation, and barely noticed by the victim. Soon, the victim begins to “understand” why the evil-doer hates the police or the person’s relatives—the very people who are trying to get that person out of the hands of their abuser.

As the victim begins to see the world—and themselves in it—through the eyes of the perpetrator, they begin to believe that they “deserve” any abuse they are subjected to, that it is all their fault and they direct their anger at themselves. There have been cases where, even after the criminal has been imprisoned or killed, the victims continued to espouse the abuser’s system of values or elements of it.

Put together, there are four conditions that contemporary researchers write much about and that make it more likely that a victim will develop Stockholm syndrome:

- a threat to physical or psychological survival;

- small kindnesses on the part of the perpetrator;

- isolation of the victim, such as through physical isolation by the presence of armed squads circling the villages suffering from famine, and lack of access to information;

- seeing reality through the eyes of the aggressor, that is, accepting the “correct” information that the aggressor is broadcasting.

Sleeping with the enemy

Sometimes researchers have expressed amazement that people who survived the horrors of 1932-33 went on to fight “for Stalin” and died heroes on the front. And when Stalin died, Ukrainians, including those who suffered from the artificial famine that he had organized, cried and couldn’t imagine how they would continue to live after Stalin. As a classic example, one young historian was astounded to analyze the story of her grandmother, Tetiana Maksymenko, whose maiden name was Skubiy and who was born in 1922 in the village of Burimka, Semenkiv County in Poltava Oblast. Maksymenko had related how her parents, two brothers and eight sisters all died during the Holodomor. She ended up being raised in a state orphanage, where the walls in her room had portraits of Comrades Lenin and Stalin, who supposedly were looking over her. By seeing the “goodness” in the aggressor, the woman was thankful to the soviet government all her life and took the death of the “Great Leader” as a personal loss.

RELATED ARTICLE: Sociologist Yevhen Holovakha on tools used to install Soviet values, the phenomenon of nostalgia about the USSR and ways to de-Sovietizate society

This was true, not only of the famine of 1933. There are the copies of the diary of a teacher by the name of Oleksandr Soloniy, born in 1911 in the village of Krynychky in Dnipropetrovsk Oblast. In the famine of 1921, Soloniy lost his father, mother and older brother Fedir. In his diary, he wrote baldly about his childish joy and gratitude to the government that his basic human need for food had finally been satisfied:

“Under Lenin, the state rescued thousands of people from starvation. We ate at a cafeteria that was opened for us hungry children… the word ‘Hurray’ has already deeply penetrated our childish souls and hearts, and our memories. All the children of the village of Krynychky, as children of the soviet people, were given sweet rice kasha and aromatic sweet coffee in the state cafeteria. And white, white bread. Each of us holds on tightly to our bread and happily gobbles it down to the very last crumb. Lenin is feeding us, saving us from a terrible death… And we have made our childish vow to always be dedicated to our Communist Party, government, Lenin and the people for caring.”

If not for the rapacious Leninist policy of “militant communism” launched after the Bolsheviks took over Ukraine, it would have been far easier to overcome the problems of the drought that year. And the number of victims would have been immensely reduced. But where could a 10 year-old in the Soviet Union have found out about this?

Access to information made a big difference, especially in families. If the parents were aware of the real reasons for the famine and told their children about this, warning them not to say anything about this outside the home, that child never developed any love for the Leader and the Communist Party. If the parents themselves believed in the innocence of their Leader or were terrified of persecution if their child were to babble their seditious ideas to someone… those children grew up isolated from information and saw the genocidal event through the eyes of the perpetrator.

RELATED ARTICLE: Kharkiv: Explained

A classic example is the ideological paradigms of communist historian Valeriy Soldatenko, who ran the Institute of National Memory under Viktor Yanukovych. In 1933, Soldatenko’s mother was eight years old, as he told one interviewer. She lived with her parents in Vinnytsia. Her mother was the first to starve to death. Infected with dystrophy, thefather took his exhausted child to Donbas, where he had heard people were living better. Having fulfilled his last wish, he fell dead at the Kramatorsk station. His daughter, who could no longer stand on her own feet, was taken to an orphanage, where she survived. She survived thanks to the care of the same government that had destroyed her parents. The orphaned girl responded with gratitude towards the new regime.

“My mother always remembered 1933 with enormous grief, with unremitting pain, but never with anger, hatred—no matter how abstracted—to those responsible for her hard fate,” the historian explained. “Among the lessons of humaneness that I learned throughout my life, those my mother taught me were not only chronologically first, but they were the most fundamental and the most definitive.”

And so, we can see how a distorted historical memory and historical trauma is transmitted on a day-to-day basis from one generation to another.

The survivor’s offspring: Learned helplessness

Some consider the Khrushchev “thaw” of the 1960s and the 1970s under Leonid Brezhnev, when people continued to be arrested and imprisoned, but quietly, and there were no mass murders, as the years of a gradual humanization of the soviet totalitarian machine and a transition to democracy. And “if not for Gorbachev with his perestroika,” the USSR would never have collapsed but would have slowly evolved into a civilized country with real rule of law and the cult of the free individual. They somehow assume that the “lull” of the sixties and seventies was the result of some form of harmonization in society, the resolution of social conflicts and flowering culture.

The truth about the unhealthy state of a society traumatized by the Holodomor and endless repressions could be seen in the widespread theft at state companies, starting with office supplies, a gram or two here and there of spirits intended to wipe down equipment, a packet of sugar or a piece of kovbasa, and ending with dump trucks full of grain, bricks, metal and so on. Nearly everyone felt the obligation to pilfer anything they could from the state, because “everything’s collective, which means everything’s mine.” The logical extension of this phenomenon some researchers see in the corruption of the 1990s. This is the consequence of the trauma of de-kulakization and requisitioning of property that went on in the thirties, when people felt robbed and subconsciously wanted to venge themselves on the perpetrator—the state.

RELATED ARTICLE: Odesa: Explained

Among the sources of this day-to-day and administrative kleptomania was the experience of the Holodomor. In those terrible years, people’s lives and the lives of their children and nearest and dearest depended on the ability to cleverly hide food from the “red broom”—which is how the communist "requisitors" were called—, to snatch a corn cob from the kolhosp warehouse, or to simply take bread away from an innocent bystander who had earned it with honest work. These are survival habits that are deeply engraved in the subconscious and never vanish without a trace.

The other side of this problem was the fear among party elites of losing access to those who distributed specialized goods, to hospitals, sanatoria and other perks. What if there was another Holodomor? I must remain in the Party at all costs, God bless it, and I’ll just keep quiet about my native tongue and if something doesn’t suit me, I’ll also hold my tongue, but I’ll be safe…

In the seventies and eighties, domestic researchers recorded an epidemic of alcoholism, drug addiction and suicides such as had never been seen in traditional Ukrainian society. In fact, suicide statistics only became available to researchers in the 1980s, when it turned out that the suicide rate in the USSR was 29.7 per 100,000. The highest rate of suicide and alcoholism was observed in Eastern Ukraine, where the experiment of making the Soviet Man made further inroads than in the country’s western region.

How does the Ukrainian individual, such as a country dweller of the pre-soviet era differ from the soviet person? For one thing, in the ability to be master of your own life and faith in the effectiveness of your own actions. One witness of the Holodomor, Pavlo Mashovets from Kyiv describes how, with only a rake and a shovel at hand, his grandfather established a massive farmstead that was later destroyed by the Bolsheviks. The scale of the artificial famine killed people’s faith that they could change things with their own actions. “The thought that I can’t do anything, that millions of people are dying of hunger, and that this is a natural disaster drove me to complete despair,” psychologist Liubov Nailionova quotes a Holodomor witness of those years as saying.

RELATED ARTICLE: Why the Russian Empire failed to assimilate Ukrainians in the 19th century

A typical situation in 1933 was a father watching his children die before his own eyes and he cannot do anything to stop it. How can he respect himself after this? “Learned helplessness” is how we describe the behavior of a person who, as the result of traumatic changes to their worldview, stops seeing any real prospects for successful actions and self-realization. Learned helplessness leads to corruption because the individual a priori feels unable to resist force. Learned helplessness also leads to unemployment and abuse on the part of management, because even when they are highly qualified, workers with a victim mentality don’t believe that they will be able to find a new job on their own. Last but not least, learned helplessness leads to despair, alcoholism, drug addiction, and suicide…

The Generation 3 Mission

The fall of 2013 was very different. It was December. I had just left a presentation of my book, “Beyond Ourselves: The socio-psychological impact of the Holodomor and the Stalin terrors” and was walking along Khreshchatyk when I found myself walking through a crowd of people with blue and yellow ribbons and ribbons with the European Union stars. I had just told my audience, referring to professional studies, that the trauma of genocide takes three or four generations to gradually disappear and I was trying to believe this myself. Filled still with the echoes of my conversations with other professionals, I didn’t even realize at that moment, that the people around me were doing what I had just been talking about in future tense…

In mid-March 2014, I ran a survey among demonstrators on the squares in DnipropetrovskΔ about whether people thought the events in Euromaidan had affected Ukrainians.[2] Most of the respondents mentioned a feeling of pride that they were Ukrainians, that collective self-worth was growing, that the once-disconnected Ukrainian society was now consolidating, that people were overcoming their fear of taking action, the fear of their own government and were awakening a desire to control it, and that attitudes towards Russia among people who once blindly supported their neighbor were changing.

RELATED ARTICLE: Ukraine in World War II

Of course, this was no reason for the passing-the-buck kind of optimism that dominated after the Orange Revolution in 2004. Economic reforms are still far too slow. The ineptness of the current government is being felt in the wallets of ordinary Ukrainians and some snails have decided to hide their identities under their shells. But that’s life. Two steps forward, one step back, three steps forward… The main thing is that, after the Euromaidan and now with the war with Russia, the ranks of conscious, active Ukrainians have grown. And most of them are indeed the third or fourth post-genocide generation.

Having gone through the Euromaidan—and here it’s not just those who were directly involved in the armed confrontations, but also those who lived through the worst moments online, felt the pain and helped out—, these young people have overcome the grip of learned helplessness, they have vanquished ancestral fears, stopped being afraid to be who they are, they have demonstrated their abilities, felt themselves masters of their own fate, and recognized the joy of action and interaction, and of a just war and victory…

And now they have a mission. To make sure that justice is part of their lives. To learn to be successful and happy here and now, in their own, not someone else’s future, lives. And to pass on the life story of a warrior-winner to their children. Only then will the curse of genocide have been properly overcome. And Ukraine’s past will let go of Ukrainians.

Δ The tiny pinpricks of hatred

Interethnic relations were very murky during the seventies. The consequences of the russification policies of that decade can be seen today. A woman aged just over 60 asked me something recently with a shrug of the shoulders: “Oh, I don’t understand Ukrainian,” she said. “I just arrived from Russia.” As it turned out, though, she’s been living in Ukraine for 40 years… What is this strange inability of “Russkies” to learn?

Another time, the trolleybus I’m riding on breaks down. I transfer to the next one and begin to look for my ticket because I have to show it to the new conductor. One of the pensioners sitting nearby half-jokingly tells the conductor, “Let the banderite pay double.” She obviously expects the passengers to approve of her joke, but no one smiles. I wonder out loud, how it is that I’m a banderite. She responds: “What do you mean? My husband is from Vinnytsia, I recognize your dialect: gotta go, gotta work…” Now I’m quite surprised, because I never said anything like this and these turns of phrase are not my style of speech at all. But now I’m in for a real shock because the other passengers in the trolleybus rise to my defense. “Why did you marry him if you don’t like banderites,” another pensioner asks her. “Heck, we’re all banderites here in Dnipro,” a stocky, silver-haired man picks up the thread. This was in the spring of 2015, after Euromaidan.