President Yanukovych’s administration has recently intensified its activity in the reformation of the country’s security sector. The reform steps include management changes in the power Ministries of the Interior and Defense, the Security Service and the National Security and Defense Council, the establishment of the Committee for the Reform of the Armed Forces and the Military–Industrial Complex. In actual fact, the pace of reform is very slow. The cornerstone strategic planning and management document – the draft National Security Strategy – was prepared back in 2010, but it has only recently been approved by the President. This article examines the reasons for the slow pace of reform and suggests that the problems stem from the system of “national values” wherein “national security” is still largely associated with “State Security”. While the government dedicated its scarce resources to managing external risks in relations with Russia, the overall level of domestic security risks is increasing. Thus, a value focus on the “people” dimension of security is suggested to step up reform.

BACKGROUND

To a certain extent, Ukraine’s security and defense sector enjoyed a successful history of reforms under the previous administrations of Presidents Kravchuk, Kuchma, and Yushchenko. First and foremost, when Ukraine became an independent country in 1991, the country’s security system in essence parted ways with the soviet totalitarian principle. A visitor to both Ukraine and Russia could probably speculate that today, in both appearance and behavior, the Ukrainian “milistia” looks more “European” than Russian.

To a large extent, Ukraine’s security sector transformations were institutionally shaped and financially supported under the framework of Ukraine’s partnership with NATO. In a way, Ukraine’s NATO integration was viewed as the driving force behind the changes for the officers of the Armed Forces, the Border Guards, and other power ministries and civil servants that participated in the Ukraine–NATO partnership program. This facilitated the change in the organizational culture. The cohort of ‘Western–minded’ professional national security managers and experts emerged in the security and defense sector and burgeoning civil society institutions and continue to influence policy-making to this day.

On the other hand, the pace of security sector reform was geo–politically affected by Russia. Ukraine’s NATO integration led to a confrontation with Russia that peaked during the August 2008 Russia–Georgia war, which divided Ukraine’s EU partners’ attitudes, with Germany and France blocking Ukraine’s NATO Membership Action Plan at the Bucharest NATO Summit in December 2008. Ukraine’s security sector services deteriorated significantly, particularly during the financial crisis of 2007 – 2009. Yanukovych’s administration attempted to alleviate the pressure applied by Russia and traded security concessions for economic benefits – which turned out to be provisional – by entering the April 2010 “gas–for–fleet” accords with Russia and legally institutionalizing the concept of a “non–bloc state”.

ENTHUSIASM AND VULNERABILITY

The Yanukovych administration appeared to have boosted security sector reform in 2010 and early 2011. Reform efforts were focused on strategic planning and naturally followed the tradition initiated by previous governments. Two important documents were drafted: the Strategic Defense Bulletin by the Ministry of Defense upon the completion of the second Defense Review (the first was in 2004) and the draft National Security Strategy that was prepared by the National Institute for Strategic Studies (NISS) to replace the 2007 document. The policy-making process was increasingly public. The draft National Security Strategy was prepared by NISS in discussions with Ukrainian and international experts, while Strategic Defense Review concepts were also discussed publicly. It was believed that these documents would become law quite soon. The National Security Defense Council resolved to speed up the process, sealed by Yanukovych’s Decree in December 2011. But the drafting and coordination process took too long and it was only recently reported that the Strategy had been approved by the President, although further work has to be done prior to completion.

The slowdown in the reform of the security sector can be explained by several factors. The first is a new environmental situation whereby the authorities’ vision of a non–bloc state was confronted with NATO–oriented government security experts that had to “adjust” their thinking. Using the management studies perspective, this resembles the conflict of “authority” and “knowledge” which management expert Ichak Azides described in his recent Twitter post: “I have often found that when there is disintegration, those who have the authority to say ‘yes’ and ‘no’ often lack the power to implement their decisions – nor do they necessarily have the knowledge to make good decisions. Conversely, those who have the information and knowledge lack the power or the authority. Worst of all, those who have the power to undermine decisions often have little or no knowledge concerning those decisions.” Second is the issue of government priorities and limited management resources. In 2011, probably the efforts of the vast majority of government analysts was directed towards fixing country’s finances, relations with Russia and energy security, and trade negotiations with the EU, while less attention was devoted to the security sector. The third important factor was apparently the absence of significant external security threats to Ukraine, that would have prompted the government to speed up its reform.

Ideologically, a new vision for Ukraine emerged and was legally stipulated. The concept of Ukraine as a “non-bloc” state was a hasty solution to the concern of Ukraine being in a ‘grey zone’ of security. But it did not actually calm this fear. The government seems to be leaning towards the vision of a ‘non–bloc’ Ukraine as a self-sufficient provider of security, reliant on its own resources and developing cooperation relations with all key regional players: “…on a bilateral and multilateral basis (particularly with NATO and CSTO) and gaining membership in the EU.” Because of the scarcity of resources available to Ukraine, at the same time, it is forced to limit its military power to resolving border conflicts and leaving relations with world powers to diplomats. Discussions continue on the size of the army Ukraine should have and priority is given to financing the defense sector and streamlining the military–industrial complex.

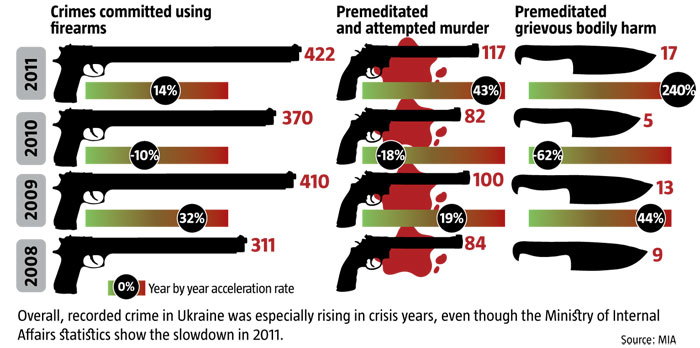

While perhaps Ukraine’s security community’s most popular topic for discussion is Vladimir Putin’s policy on Ukraine, what seems to be overlooked is the increasing level of crime and violence in the ”policing” segment of security. The violent crime trend is growing. Whereas 140 bank assaults were reported in Ukraine in 2011, this year the robbery rate has accelerated. As a challenge to public safety, the four explosions in rubbish bins in Dnipropetrovsk on 27 April 2012, injuring 30 people, raised concerns both in Ukraine and abroad over the reliability of Ukraine’s security system. Statistical data show an increase in recorded armed crime:

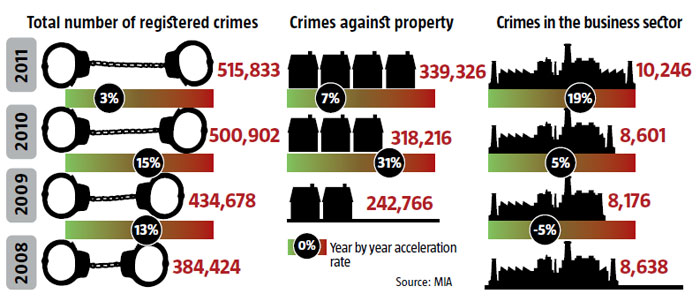

Overall, recorded crime in Ukraine increased significantly in crisis years, even though the Ministry of Internal Affairs’ statistical data shows a deceleration of this trend in 2011.

This dynamics is troubling if Ukrainian trends are compared with EU data where the crime trends decreased noticeably in 2006 – 2009.

THE KEY CHALLENGE

One could attribute the slow pace of security reform to the complexity of government management and the lack of coordination among various government agencies. But the greater problem seems to be the lack of a key pillar of strategic management value-based leadership. According to Volodymur Gorbulin and Anatoliy Kachynsky, it is these values that are the most important element in the “security triad” of national values –goals and interests. In the system of values, “The defining and supreme value for the human is him (her) self and his (her) life…Thus, a person is the basic element of all subsystems that form the national security system.

But the humanist values in Ukraine were suppressed by the years of the soviet and Russian Empire’s legacy that cemented the system of values dominated by State Security, not people security. Interestingly, Volodymyr Gorbulin and Oleksandr Lytvynenko found the fundamental presence of the outdate term “state security” in Ukraine’s Constitution, Article 17. It is very tempting to reduce State Security to serving and protecting those with power and money. The presence of this system is very visible in today’s Ukraine: in politically–motivated prosecution, the harassment of businesses by tax authorities, motorcades of protected senior State officials that cause gridlocks, cases of abuse at police stations, court bans of peaceful protests motivated by “national security” considerations, the monopoly of the police and not private guards to carry firearms and the political appointment of loyalists to key posts in the security sector. True security sector reform will be successful if reformists rely instead on Ukrainian traditional values that are similar to modern democratic values: personal freedom, taking care of the family, democratic governance, entrepreneurship and respect for private property, and of course patriotism and the virtue of service for public good. The managers that promote these values are leaders that will sooner or later carry out the suspended reform as well as other reforms needed for this country. Such successful reform will not be possible in an isolated Ukraine, but in an open one, carried out by leaders that enjoy the support of a broad societal coalition. Management scholar, Peter Drucker, rightly said that “in times of upheavals”: “One cannot manage change. One can only be ahead of it…To be sure, it is painful and risky, and above all it requires a great deal of very hard work. But unless it is seen as the task of the organization to lead change, the organization— whether business, university, hospital and so on—will not survive”. This is even more true of such a complex organization as the national security sector.