In a series of articles published during Russia’s last presidential election, Vladimir Putin outlined plans to increase the country’s energy, geopolitical and military impact, reclaim its status as a key link in the future structure of Eurasia, and squeeze the US out of the Eastern Hemisphere.

PATH OF LEAST RESISTANCE

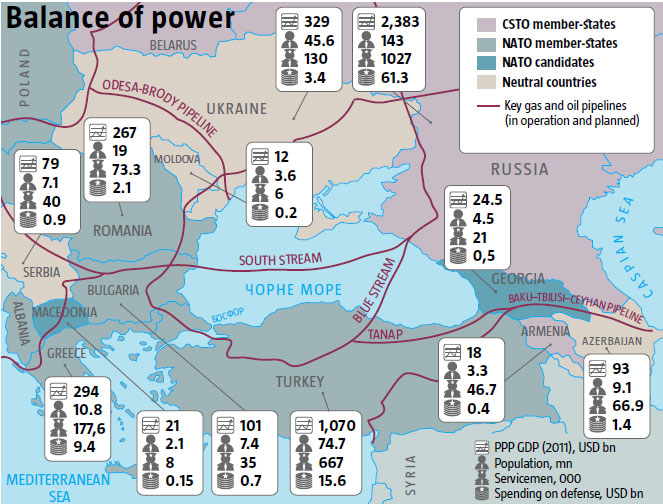

Meanwhile, Russian foreign policy records show that given few options for expansion westward and over the Baltic States, the Kremlin has typically focused on the region of least resistance to the south, including Black Sea and Caspian Sea states and Central Asia. None of those is yet able to compete with Russia in terms of its military, economic or demographic capacity. As resistance to the growing impact of China in Central Asia is an unrealistic objective, the Kremlin is likely to see its increased presence in the Black Sea region, including the Caucasus, as a priority.

In addition to the intensified activity in the Caucasus that accompanied Mr. Putin’s previous ascent to power, with Russia’s military intervention against Georgia in 2008 marking his shuffle to the premier’s office, preparations have been made for an expanded Russian naval presence in the Black Sea. At this point, Russia’s Black Sea Fleet has only one submarine. According to the Fleet’s Commander, Rear Admiral Aleksandr Fedotenkov, it should have seven by 2017. New naval ships are currently being built at Russia’s Baltic shipyards. In summer of 2011, Major General Aleksandr Otroshchenko, Chief of Russian Black Sea naval aviation, stated that strategic aircraft, including TU-23M3 bombers, must be returned to the Black Sea Fleet.

Clearly, this is why the Kremlin wants new concessions from Ukraine in terms of its Black Sea Fleet and the green light to “upgrade” its weapons, which will in fact end up increasing in size and number as well. On 20 April, Grigogiy Karasin, Russia’s Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs, mentioned that a series of new deals had been drafted regarding the movement of Russian military units beyond their deployment areas and the crossing of Ukrainian borders by ships, supply vessels, aircraft and military staff of Russia’s Black Sea Fleet. The Kremlin is also developing a backup base in Novorossiysk that could become the key deployment point for Russian Black Sea Fleet reserve troops if talks with the current Ukrainian government fail to achieve the desired results or if a new government revises the terms.

In 2005, the Russian government approved a federal programme to develop the Black Sea Fleet on the territory of the Russian Federation from 2005-2020. It will cost the government nearly RUR 92 billion or over 3 billion dollars. Given Mr. Putin’s recently declared military ambitions, the programme may eventually receive much more than that. In 2010, the Russian government spent RUR 2.8 billion (nearly 90 million dollars) to set up the base in Novorossiysk. Funding for 2012 is estimated at RUR 9 billion (300 million dollars) according to SpetsStroy (Special-Purpose Construction Company), the builder of the base. Regardless of whether the increased Sevastopol armaments lead to concessions from Kyiv, Russia will still increase its military presence in the region through its base in Novorossiysk.

Apart from the ambition to expand its influence in the Black Sea region, Russia is motivated by Georgia’s consistent movement toward intensified collaboration with the US and NATO integration, as well as Turkey’s growing authority in the region. Russia’s Blue Stream gas pipeline, as well as the yet-unfinished South Stream and Burgas-Alexandroupoli pipelines will add to Moscow’s incentives, now economic, to increase its military presence.

NEO-OTTOMANISM

Turkey’s growing influence in the region and its intensifying policy regarding its neighbor states, especially countries that had once been under the control of the Ottoman Empire, are plain to see. Neo-Ottomanism is the newly-coined term for this. Of course, at this point, emphasis is being placed on a new hegemony based on soft power, trade and economic dependence, thus orienting the region toward Ankara. Turkey’s swiftly growing economy, including the 16th fastest-growing GDP worldwide, contributes to this. By now, Turkey has become the biggest market for some of its neighbours. Ukraine is no exception: it exports more goods to Turkey (worth USD 3.95 billion in 2011) than it does to any other European country. To boost its economic capacity, Ankara is working hard to liberate itself from energy dependence, including dependence on Russia, as well as on gas transported through Ukraine, Romania and Bulgaria that had once constituted a large share of the goods it imported and consumed. Meanwhile, Turkey will impose a similar dependence on itself among states in the region. In addition to attempts to monopolize the flow of gas and oil from the Caspian Sea region, this includes the intention to take over most transit of Russian fuel to Europe and the Mediterranean. Firstly, South Stream, if eventually built, will operate exclusively in Turkey’s economic zone. Secondly, Ankara keeps restricting the transit of fuel cargo, primarily tankers carrying Russian oil, through the Bosporus.

Moreover, Turkey’s leaders would like to completely take over maritime trade between the Black Sea states and the outside world. In April 2011, Turkey’s Premier Recep Tayyip Erdoğan voiced his intention to build a shipping canal between the Black Sea and the Sea of Marmara by 2023 and to relocate all flow of cargo there from the Bosporus. Unlike the Bosporus, which is regulated by international agreements, the new canal will be owned by Turkey alone, giving it the power to decide on tariffs and regulations for foreign vessels.

Turkey is trying to restore its status as a key state in the Islamic world, at least in the Middle East, while distancing itself from Washington by supporting only US initiatives that it can benefit from. Meanwhile, it appears ready to get involved in an open conflict with America’s strategic allies in the region. One example was the supply of “humanitarian aid” to Palestine that brought Ankara and Tel Aviv to the brink of an armed confrontation.

BETWEEN MOSCOW AND ANKARA

As Turkey and Russia increase their influence in the region, the EU seems less interested, and more pre-occupied with its own problems. The region also risks losing its priority status for the US as it plunges deeper into the confrontation with China in the Asia – Pacific region. As a result, the presence of the EU and US in the Middle East is likely to remain soft, limited to the support of consistent and voluntary allies.

Washington is unlikely to abandon support for Georgia and the neutral buffer states that continue to resist Russia’s ambitions to absorb them, yet are not ready for more intense collaboration with the US. However, this will restrict the scale of US support and the array of measures used. In this case, the White House may actually benefit by counterbalancing the influence of Russia and Turkey, supporting the latter until a certain point in time, thus turning Turkey’s focus away from the Middle East to the Black Sea region to a certain extent.

Strengthening Turkey and cooling its relations with the rest of the EU while reducing US attention to the region could lead to significant transformations in Greece’s geopolitical objectives. Athens might have to look for a more effective “partner,” and Putin’s Russia would make a plausible candidate. The issue was raised by a local pro-Russian party during recent elections in Greece. Some say this might help Moscow negotiate the rental of a Greek naval base to replace its base in Syria in the event that Assad’s regime is overthrown.

The base in Greece, however, could eventually have a much more powerful effect, aimed at not only increasing Russia’s presence in the Mediterranean and the Horn of Africa where the Russian Navy is now performing anti-piracy operations, but also at becoming a significant factor in keeping warships of unaffiliated countries out of the Black Sea. Moreover, Greece, which is now trying unsuccessfully to clamber out of debt, could be the starting point for a renewed Russian presence in the Balkan States including Serbia, Macedonia and Bulgaria. Pro-Russian lobbyists are becoming more and more proactive there. This could lead Bulgaria to the group of countries loyal to Russia given Turkey’s growing ambitions and its current joint economic projects with Moscow.

If the presence of NATO and the US in the region fades and the EU Southern Gas Corridor hinges on Turkey, then the geopolitical split of the South Caucasus into pro-Russian and pro-Turkish countries will center on the energy factor. Moreover, the possible overthrow of the current regime in Iran would wipe out the last remaining multi-vector policy options for the Caucasus states. If that happens, they will have to choose between Moscow and Ankara. Tbilisi and Baku will opt for Ankara while Erevan will grow even more pro-Russian (the two countries agreed in 2010 to extend the lease of a Russian military base in Armenian Gyumri until 2044).

Nuclear weapons will remain Russia’s key advantage over Turkey, but past decades have proven that a country of Turkey’s size and power has a good chance of catching up with its competitors by developing its own nuclear weapons. If that happens, it may add some nuclear flavor to the confrontation in the region.

IN PURSUIT OF A PERFECT BALANCE

In this Russian-Turkish model of the Black Sea region, it is important for countries that are equally disinterested in falling under Russian or Turkish influence to find ways to keep outside powers focused on this part of the world. This means either maintaining a US presence or reviving Germany’s interest to counterbalance Russian influence and the growing impact of Turkey, at least for some of the Black Sea states, including Ukraine, Moldova, Romania and possibly Bulgaria and Georgia. Otherwise, Kyiv and Bucharest will have to decide which of the two potential regional hegemonies would be most acceptable and tactically beneficial. Collaboration with Turkey should be a clear priority for Ukraine as long as the biggest threats to its sovereignty and national identity come from its northeastern neighbour. This would allow Ukraine to walk away from Russia. In the current situation, Kyiv could establish relations on an allied, if not totally equal, basis with Ankara. Unlike Turkey, the best that Russia can offer Ukraine is a satellite role, while the worst case scenario would be a gradual loss of sovereignty and dissolution under Mr. Putin’s neo-imperial project.

Thus, Ukraine should focus its efforts on launching a regional Black Sea security entity possibly involving all Black Sea states, excluding Russia and its determined allies. The best option would be to set up an entity supported by a nuclear power, meaning the US, and involving European countries that seek real containment of the Kremlin in the region, such as the UK, Poland and the like. This would be a Baltic-Black Sea entity without a defined intra-regional leader, such as Turkey (which will happen if the scale of collaboration is restricted to the Black Sea region and the Caucasus). Thus, Kyiv would be left with some space to affect the decision making process.

After all, a Black Sea entity involving Turkey and Ukraine, but not Russia, could become an efficient tool in solving the region’s energy security dilemma, even if Turkey plays the key role in fuel transit. Its army’s power would guarantee that outside forces would not intervene in the South Caucasus once again, repeating the scenario of Russia’s 2008 intervention in Georgia. This would secure the key energy transit communications of the Black Sea and European states with the Caspian region.

Moreover, a possible US military operation against Syria and Iran could provoke a revolution in the European energy market as the gas export potential of Turkmenistan, Iran and the Persian Gulf Arab states is considerably higher than that of Russia. Firstly, they have much larger reserves of gas, and secondly, Russia consumes much more gas domestically, especially in the cold winter months. At the same time, the natural conditions for gas extraction and transit in these states are no more challenging than those in Russia, while the distance to key consumers in Europe is comparable to the distance from Russia’s key gas fields in the Arctic Circle and remote parts of Siberia. In contrast, the main factor restricting the export of Asian fuels to the EU in recent decades was almost exclusively the political risk associated with strained relations between Western countries and dictatorships in potential fuel supply and transit states.