A ranking of election law violators released on September 4th by the OPORA (Resistance) NGO featured the Party of Regions and its representatives in centre stage. The statistics tracked political parties and candidates running for parliamentary seats. 188 violations by the Party of Regions were registered in the month of August alone. In second place with 47 registered violations were several formally “independent” candidates with close ties to the Party of Regions. The total number of violations made by opposition forces fulfilling the required 5% threshold, including Batkivshchyna, UDAR and Svoboda, as well as their first-past-the-post (FPTP) candidates, was eight. The most common violations by ruling party include abuse of administrative leverage and voter bribery (109 and 103 instances respectively), interference with the political activity of other candidates (58), illegal campaigning (42), and interference of law enforcement agencies in the pre-election process (9).

Unlike their more cautions Kyiv bosses, Party of Regions functionaries in other regions never concealed their desire to return to the soviet reality where the party and the government were one, as it is in Putin’s Russia today. Andriy Shyshatskyi, First Deputy Head of the Party of Regions’ oblast office and Head of the Donetsk Oblast Council, claimed openly at a party conference, “The Party of Regions is the party in power; the Party of Regions and the government are one and the same.” Thus, the ruling party is putting all of the government’s financial and administrative resources behind its own re-election campaign. In a statement reminiscent of the soviet era Communist Party, the Party of Regions’ Donetsk Oblast office announced the following strategy: “Ensure the cooperation of local authorities, FPTP candidates and party organizations for the solution of socio-economic problems in cities and counties of Donetsk Oblast.” Similar approaches are now in place in most parts of Ukraine where the Party of Regions gained control following the “free” 2010 local elections.

FOLLOW THE LEADER

Administrative coercion is the most ubiquitous in South-eastern Ukraine, which the government believes to be its core electorate. Thus, any efforts by the opposition there outrage the Party of Regions. Apart from the Donbas, this is also a clear trend in Odesa Oblast, where Head of the Oblast Voters’ Committee Anatoliy Boyko has noted increased efforts by the ruling party to interfere with the campaigns of other candidates. These manoeuvres threaten the legitimacy of the election process in Odesa Oblast, and include the libelling of competitors, indirect bribery of voters, and involvement of civil servants and public funds in the Party of Regions’ campaign. Sometimes these efforts go beyond sound reason. Sevastopol City Council has banned a fan zone for Vitaliy Klitschko’s boxing match in the city because he is the leader of the second most popular opposition party.

Attempts to spread the use of administrative leverage to Central and even Western Ukraine are crystallizing as well. In his address to the Head of the Central Election Commission, BYuT’s Mykola Tomenko noted that local authorities intentionally interfere with meetings between voters and opposition FPTP candidates. Their call to action came in a letter entitled “Working with Competitors in Single-Member Constituencies,” signed by Anatoliy Prysiazhniuk, Head of the Party of Regions’ election campaign in Kyiv Oblast and Chair of the Kyiv Oblast State Administration. The directive was sent to heads of district, city and county election offices and district coordinators from the Party of Regions.

According to BYuT-Batkivshchyna MP Volodymyr Bondarenko, “Social Services in Kyiv have hired a hundred new workers each at public expense. They will deliver gift packages to people as if from the local civil service while promoting specific candidates.” A similar practice is being used in Bukovyna. According to UDAR’s oblast office, social workers collect information on political preferences from people in local villages and campaign for the party in power. Based on the data collected by social workers, opposition party supporters are likely to be removed from the voters’ register under various excuses.

ARE YOU LOOKING FOR TROUBLE?

Administrative pressure takes many forms—intimidation by law enforcers, the assault of opposition candidates, civil activists and campaigners by unidentified assailants, forced registration of teachers and other public sector employees for the Party of Regions, abuse of administrative leverage for propaganda purposes, and “courtesy letters” in which campaign contributions are “requested” of business owners.

Opposition forces and NGOs monitoring the election process have recorded and disclosed several troubling developments. On July 31st, the Central County Court of Mykolayiv arrested Liudmyla Nikitina, head of the United Opposition’s election office in Pervomaysk, a town in Mykolayiv Oblast, as a preventive measure. On August 29th, leader of UDAR’s office in district No. 105 in Luhansk Oblast Serhiy Zlobin was arrested. On September 1st, a representative of Svoboda in district No. 128 in Mykolayiv Oblast was arrested at the railway station in Mykolayiv when he arrived from Kharkiv.

Apart from this, opposition candidates often face criminal charges and are summoned to interrogations. Cases against Ihor Reshetnyk and Oleksandr Romaniuk, two United Opposition candidates, have recently been launched in Mariupol, Donetsk Oblast. Volodymyr Derkach, a United Opposition candidate in district No. 41 and proactive participant of protests arranged by Chornobyl victims in Donbas last year, was summoned to an interrogation and is accused of beating a student and forging documents that entitled him to privileges as a Chornobyl victim.

BYuT’s MP Mykhailo Sokolov recently found himself linked to the case of terrorists who set four bombs in Dnipropetrovsk in spring 2012. The investigation found that the two suspects charged with arranging the explosions worked as Sokolov’s advisors, and their letter with demands was allegedly printed at his office. Sokolov has already received two invitations to interrogations and ignored one. As a result, the SBU has threatened to bring him in for interrogation by force.

Valentyn Koroliuk, a United Opposition candidate from district No. 154 in Rivne Oblast, was recently threatened with physical harm, according to Batkivshchyna. On August 27th, an unknown assailant tried to break into the apartment of Svoboda’s Andriy Bortnik who is running in district No. 71 in Rivne Oblast. Oleksiy Davydenko, UDAR’s candidate in district No. 216 in Kyiv, has reported intimidation as well. On August 31st, his office was robbed. On September 3rd, his car was stolen. He has also received anonymous threats.

Sometimes the ruling party uses soft intimidation tactics, threatening to fire opposition members and activists. UDAR’s candidate in district No. 61 in Donetsk Oblast Yevhen Korzh reported that he had been fired from an engineering plant before the party meeting on July 31st where he was nominated because he refused to quit the campaign. The same thing happened to Roman Volkov who is running as UDAR candidate in FPTP district No. 43. According to Volkov, his boss summoned him after he returned from the UDAR meeting in Donetsk and demanded that he cease his political activity, otherwise, he would be sacked.

In some cases, the pressure placed on opposition candidates does work. In Zaporizhzhia Oblast, UDAR candidate Oleksandr Volkov resigned from the campaign in FPTP district No. 80. He said that his nomination posed a threat to his successful business.

Reports of pressure on average activists are mounting, coming from virtually all parts of Ukraine on a daily basis. They include interference with the distribution of promotion leaflets, attacks on opposition party tents, blocking of promotion cars by the road police, attempts at psychological pressure on average activists, recording of their personal data and much more. In some cases, the police are directly involved in such efforts—“unknown men of athletic appearance” do the dirty work while the police are conveniently absent. A group of unknown men attacked activists while they were distributing promotion brochures for candidates other than Speaker Volodymyr Lytvyn in the district in Zhytomyr Oblast where he is running. The brochures were mostly about Lytvyn’s role in the passing of the notorious language law. Lytvyn’s brother Petro was recognized among the attackers. He denied allegations of his involvement in the incident. Later, the activists were arrested, brought to the police station and beaten up again.

In Rivne Oblast, an unknown man sprayed something on a promoter of the United Opposition. She was taken to the hospital with symptoms of poisoning. On July 30th, unknown assailants burned the car of Iryna Zolotariova, head of the United Opposition’s campaign office in Izmail, Odesa Oblast. On August 8th, a fire broke out in the garage of Maksym Volkov, leader of the Izmail Youth Union, a member of the United Opposition. An unknown man assaulted Taras Diachenko, an UDAR activist in Dnipro District, Kyiv. On September 9th, a group of unidentified people attacked activists who were spreading leaflets about the crimes of the ruling party. The attackers insisted that the activists accompany them to a police station while refusing to provide any police ID. A group of policemen and Berkut special forces crashed a campaign tent for Batkivshchyna and injured activists and a Batkivshchyna candidate from a FPTP district.

The intimidation of average activists stems from the government’s desire to prevent inconvenient information from reaching voters. There is no reason to expect that this pressure on the opposition and the media will stop. These actions are likely to mount and the arsenal of tools is likely to expand as Election Day draws nearer. So far, the government has not yet exploited the loyal judiciary for election purposes to the extent that it could.

BRIBING TAXPAYERS AT THEIR OWN EXPENSE

Incentives from pro-government candidates include conventional bribery at the candidates’ expense and speculation about efforts to get funding for social projects in candidates’ districts that are already in the budget. The candidates use taxpayer money to open playgrounds, buy medical equipment for hospitals and fix roads, advertising as their personal contribution what is in fact merely the fulfilment of government commitments.

This practice is most common in districts where candidates come from families that have power but no extensive business assets of their own. They are reluctant or cannot afford to pay their own money for the election campaign. Apart from the case with Volodymyr Lytvyn who got over UAH 80mn for a campaign in his district, Artem Pshonka and Oleksiy Azarov, the sons of the Prosecutor General and Premier, have significant public funding for campaigns in their districts in Zaporizhzhia and Donetsk Oblast. Both allocations are estimated to be at least UAH 60-70mn each. Over UAH 50mn was allocated from the budget before the election for social projects in Kyiv Oblast district No. 97 where Serhiy Fedorenko is running. He is the leader of the Party of Regions’ Brovary office, better known as Premier Mykola Azarov’s massage therapist.

The Party of Regions does not seem to be concerned with the fact that its candidates are using taxpayer money for election campaigns on a massive scale.

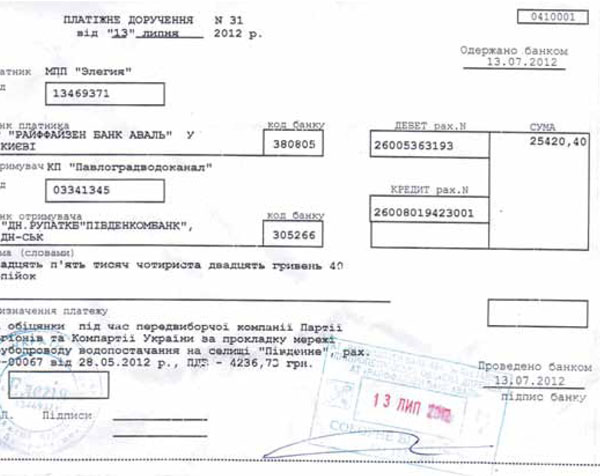

Sometimes budget funds are not enough and the government uses administrative leverage to force business owners to pay for its candidates’ campaigns. In particular, local authorities sent “courtesy letters” to company owners with requests to transfer a certain amount to a specified bank account. The most common purpose listed in such letters was “social projects” for developing the oblast, county or town. One telling example was reported by Svoboda: on September 14, 2012, a businessman from Dnipropetrovsk Oblast released copies of invoices demanding his contribution to fund the election campaign of the Party of Regions and the Communist Party. He was told that his business would be closed down if he refused to pay the bill. He did so but indicted the true purpose of the transactions in the invoices as a response to the intimidation by the two parties. Invoice No. 31 dated July 13, 2012, paid by the Elegia company says that the transfer was made “To cover pre-election promises by the Party of Regions and the Communist Party of Ukraine to install a water supply system in Pivdenne village” (invoice SF-00067 dated May 28, 2012) and “To cover court fees for the election campaign of the Party of Regions and the Communist Party of Ukraine under the order dated September 16, 2012, case No. 5005/2590/2011” (see copy of the invoice). Shortly thereafter, the businessman was summoned to the SBU office in Pavlohrad where he lives.

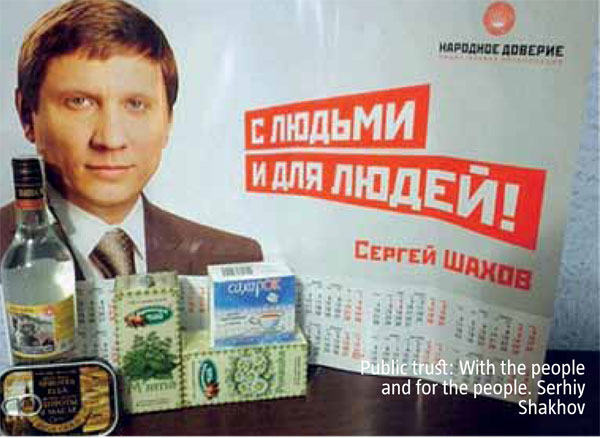

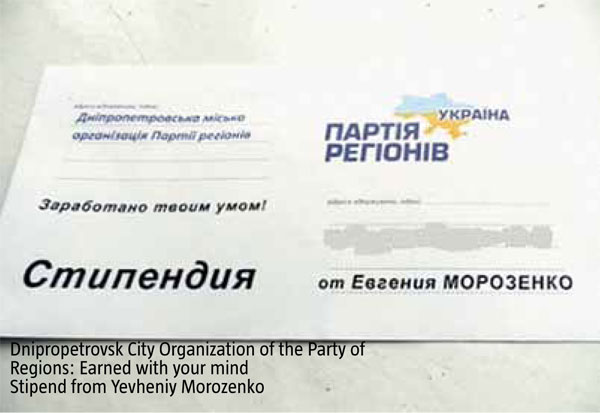

Before the official election campaign kicked off, no one could hold candidates liable for bribing voters. Under the law, bribery is classified as “charity” until nominees get their candidate certificates from the Central Election Commission. Still, most candidates have continued to bribe potential voters even after the election campaign started. They are doing so through hastily registered charitable funds, making the cause perfectly legitimate. In addition to distributing gift packages familiar from earlier election campaigns, some candidates have been more creative. They pay for a village or city day celebration, take people to football games, offer free haircuts or breast examinations, fill cell phone accounts, give out free eyeglasses, distribute envelopes with money (in amounts ranging from UAH 50 to 300) or gifts for school or pre-school students.

So far, only one instance of voter bribery has been officially recorded by the court. Odesa’s Administrative Court of Appeals ruled that Davyd Zhvania, a FPTP candidate in district No. 140 and a turncoat, bribed voters by distributing free school uniforms to students. The ruling was sent to the Central Election Commission, which merely issued a warning. Meanwhile, in the case of the premier’s son, the court was forced to deny that Azarov Jr. had engaged in bribery using public funds, and dropped the charge immediately after it was filed.