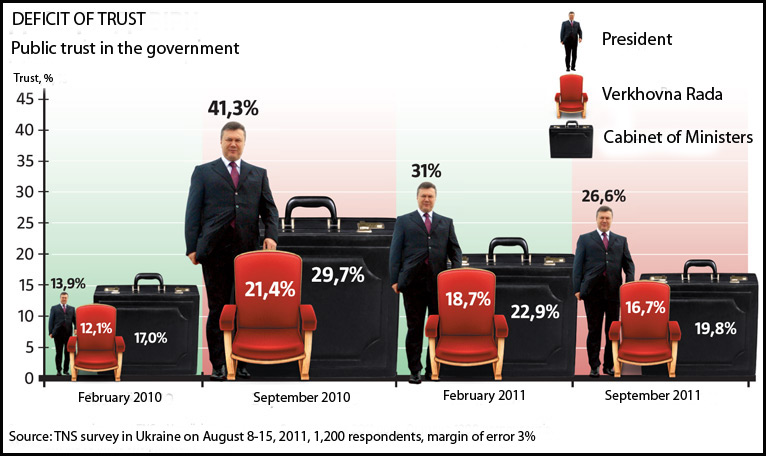

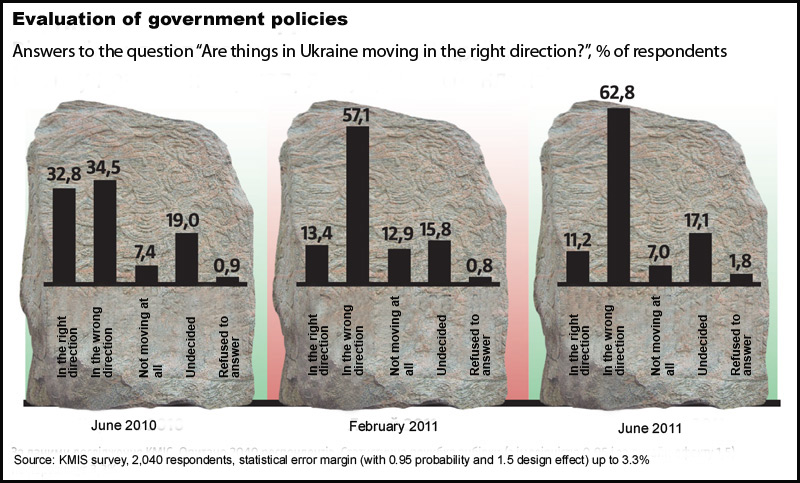

Recent opinion polls show that an increasing number of Ukrainians are losing trust in key government institutions. A TNS survey in Ukraine revealed that no more than 20% of the population trust the president, parliament, Cabinet of Ministers and the judiciary. The Kyiv International Institute of Sociology found this past summer that nearly 63% believe that things in the country were moving in the wrong direction.

However, despite this near total dissatisfaction with the government, there are still no signs of an imminent autumn revolution which opposition politicians said in September was bound to take place. They promised an almost Egyptian scenario, but the biggest protest, on Independence Day, involved a little over 10,000 people. On average, protests attract 5,000 Ukrainians. They must reach a critical point, before turning into mass-scale protests worthy of being called a revolution. While there are signs showing that we are coming closer to such an event, future developments will hinge on the actions of the government and the opposition.

GROWING PROTEST POTENTIAL

Sociologists say that the country is in for more protests. “The government is now pursuing a strict policy of curtailing social benefits for the underprivileged, and these actions will cause a reaction from the affected social groups,” Razumkov Center expert Mykhailo Mishchenko says. For example, NGO representatives who were among the people that stormed the parliament on September 20 already refused to continue negotiations with the government and adopted a firm stance: full satisfaction of their demands or new protests.

Sociologists have calculated that the Party of Region’s fear of a new revolution may become a reality if discontent with the government causes 7-10% of the population to join protests at the same time. However, there is presently nothing in play that could unite the disparate protesting social groups. Moreover, sociologists note that there is no direct link between a high level of dissatisfaction with the government and the likelihood of large-scale protests. Not everyone who speaks critically of the country’s leadership is prepared to personally participate in protests, demonstrations or other mass events. In 1991–2004, the highest level of national discontent was recorded in 1998-99, but there was no social explosion at the time. Consequently, other factors in addition to the dropping standard of living must come into play for a revolution to take place today. Two such factors are a hope to achieve changes for the better and the efficiency of alternative forces (the opposition) in defending the interests and expressing the will of Ukrainians.

CHARACTER OF PROTESTS

That the social temperature is rising is to be expected, Mishchenko says. It is a typical reaction to falling trust in the government when the latter is gradually losing its legitimacy. However, the nature of the protests has changed significantly since the Orange Revolution. Active citizens used to rally largely under political slogans, such as demanding an end to corruption and Russification.

Today, issues have come to the fore that affect simple citizens directly: the business climate, rising prices, access to education, illegal construction in residential districts, etc. “The social groups that already have their own organizations will be able to initiate protests and perhaps demand at least partial fulfilment of their demands. This was the case with the entrepreneurs who came to the Maidan in the winter of 2010. Afghan war veterans and Chornobyl disaster victims, who stormed parliament, also have organizations, just like students do. If teachers and doctors were also organized, they would also actively participate in protests,” Iryna Bekeshkina, director of the Democratic Initiatives Foundation, says. This way, in many cases the government is spared protests due to the lack of an independent trade union movement in the country.

Also, unlike previous years, people are more readily involved in protests initiated by NGOs rather than political parties. Protesters themselves explain this by their disillusionment with the opposition political forces. Discontent with politicians has gone so far that most of their calls fall on deaf ears. People do not rush en masse to defend Yulia Tymoshenko or Yuriy Lutsenko, even though the political motivation and the unfairness of their trials are plain to see.

The first signs of changes could be discerned back in 2010 when Ukrainians essentially ignored opposition-organized rallies against the Kharkiv Treaties, but then, several months later, entrepreneurs’ protests in Maidan involved many thousands of people.

There is also a lack of solidarity among those already protesting. People were not much stirred by the absurd arrests among protesting entrepreneurs over allegedly damaged paving stones on Khreshchatyk, by the controversial case of the ProstoPrint company which produced T-shirts with a popular anti-presidential chant or by the lawless conduct of top officials and their relatives.

“A Party of Regions MP shot seven people and no-one speaks out! When there is a need to defend the constitutional rights of some Ukrainian citizen, people begin to suspect that the victim may turn into a political leader. The government has ruined Denys Oleinykov’s business, which it took him years to build, and driven his family out of the country, and people say they will come out to defend his rights only when they see his political program,” Oleksandr Danyliuk, leader of the Common Cause movement, says with a hint of disgust.

IMMATURE ALTERNATIVE

When protest groups are disunited and lack of coordination and solidarity, it is critical to have a force that would guide and unite people. It would be natural to expect the political opposition to fill this niche. However, one gets the impression that the opposition has failed to notice the change in social attitudes. Politicians continue to address the residents of the tent village located near the Pechersk District Court primarily with calls to “defend political competition” and speak about immediately replacing the government, disbanding parliament and impeaching the president. The protesters themselves who spoke to our correspondent tend to make more frequent references to rising prices, the retirement age and freedom of expression.

As long as the opposition does not have a clear, realistic and citizen-friendly action plan, the majority of the discontented will prefer to defend their interests on their own, without politicians. Meanwhile, the latter are trying to lead people while taking advantage of their protest sentiments, often in an excessively straightforward fashion. “The vacation season is over; people are returning to the capital. The parliament passed retirement legislation and will be implementing other unpopular decisions. The socioeconomic situation will continue to deteriorate, and then people will take to the streets for sure,” a BYuT MP explained to The Ukrainian Week. He wanted to describe how the opposition would be restoring people’s trust but failed to show what role opposition parties would play in the process.

Another trend noted by experts is the growing significance of social networks in shaping public opinion and organizing protests. In conditions when most TV channels tend to reflect the views of their owners, information exchange in social networks remains largely free of third-party loyalties. The internet is also a convenient tool for spreading information about planned events and attracting people to them. However, Ukrainian public activists say the role played by social networks in their organization should not be overestimated.

“There will be no Facebook revolution. The amount of cursing on Facebook is not indicative of the number of people ready to participate in mass events. If all those whom we invited to join the protest on Independence Day came, we would have had 50,000 people. This is a good way to inform journalists about our activities. But those who come are largely people we know personally or have invited on the phone,” Danyliuk says.

CONSTRAINT FACTORS

Total distrust in politicians of both the pro-government and opposition camps remains one of the key factors that now preclude a protest movement that would bring together various social groups to fight for a common cause. Even though the current administration is not favored by more than half of the population, only a low percentage of Ukrainians dare voice their discontent. Citizens are simply do not believe a new government team would differ from the current one in anything significant, except its colors. Most experts believe that only a total socioeconomic downturn, such as the fall of the hryvnia, could be the uniting factor to set off a revolution.

The government may also rally people against itself, even though it seems to benefit from they way it handles protesters. When some social group or another begins to firmly speak out against the government, the latter pretends to make concessions and the protesters wrap up their activities. To constrain the most unruly activists, it puts a few under arrest and launches criminal investigations. This tactic dented the resistance of small entrepreneurs who were never completely satisfied with the tax reform they were offered. A similar approach is being used against Afghan war veterans, though they have shown more persistence than the entrepreneurs.

And so the government will continue to dampen the protests of each and every social group that finds the courage to speak out openly against government reforms, Valeriy Khmelko, head of the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology, says. At the same time, the tactic of faked concessions and pointed repressions may come back to haunt the Party of Regions. Instead of frightening the active part of society, criminal cases opened against public activists may provoke the opposite reaction if they affect sufficiently wide circles and evoke a feeling of insecurity and hence the need to unite for self-defense.

Experts note that a lack of a powerful protest movement is also linked to the fact that civil society in Ukraine is still in a nascent state. Ukrainians do not identify with people or social groups that are pressured by the government but rather are concerned with their own problems. If their rights are violated, social groups are left to fight on their own. The country’s leadership will only change its behaviour when faced with pressure from society at large.

In these conditions, and given the helplessness of the opposition, authoritative civic figures are beginning to play a much greater role: these are opinion leaders, respected people who can explain the situation to the people and call them to influence the government in efficient ways. Even if the “flower and conscience of the nation” fail to deliver, the expanding protests will involve an increasing number of social groups, the government will make mistakes in counteracting them and new leaders will emerge. However, this will take time and energy that could be used much more efficiently now to replace the current government and control those who come to take its place.