As the entire world was rethinking militarist ideologies and returning to the humanist ideas reflected in the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights (December 1948), the totalitarian Soviet Union remained quite “exotic” with its Gulag, an infamous system of concentration camps. Moreover, the Soviets had just begun to designate special camps—the so-called osoblagi (special-purpose camps)—for “especially dangerous state criminals” (see Notes). After the Second World War, this category comprised primarily members of armed resistance forces who had fought against the Soviet regime and were taken captive: OUN underground activists, UPA fighters, Baltic “forest brothers”, members of the Polish Armija Krajowa (Home Army), etc.

LIVING IN SPECIAL-PURPOSE CAMPS

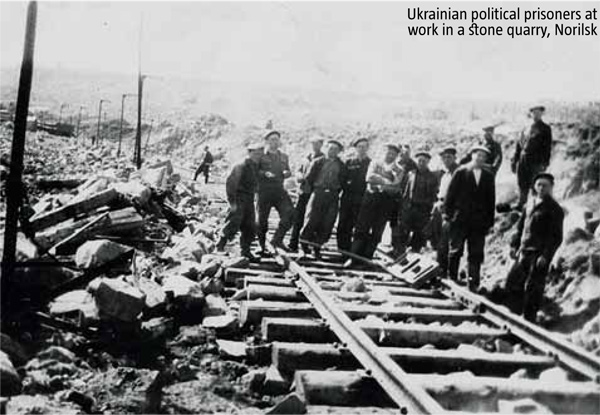

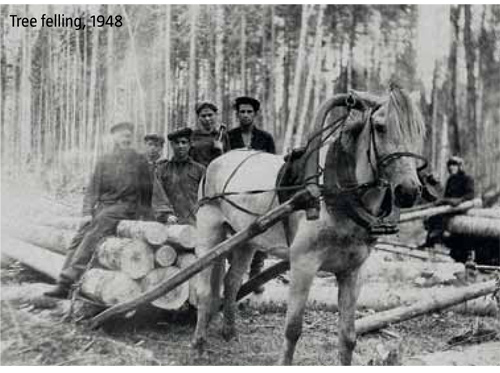

The residential quarters of osoblagi were kept under prison-like security: windows had iron bars; barracks were locked up for the night; inmates were not allowed to leave the barracks outside of working hours. The residential space afforded to inmates in 1948 was half the size of that in general-purpose forced labour camps: one square metre per person. Inmates of special-purpose camps were utilized for especially difficult work, including mining and industrial and residential construction. The excesses of camp administration, armed guards and MGB escorts were outrageous and, most importantly, they acted with total impunity. Special-purpose camps were the final and most cynical Stalinist invention in the long history of the Gulag, a system designed to destroy people first morally and then physically.

Convicted criminals were another tool used by the authorities to harass inmates. According to official documents, such convicts (urki, urkagany or blatari in criminal slang) were not supposed to be placed in special-purpose camps, but the authorities intentionally sent groups of them there. Camp administrators turned a blind eye to the abuses of criminals, who bullied political prisoners and established much-desired discipline in the camps. Still, criminals were a minority in the osoblagi, with political prisoners outnumbering them five to one. Camp administration assigned criminals to do lighter work, largely on the territory of the camp and issued them full rations for meeting work quotas. This was done to ensure that the criminals were in good physical condition to fulfil their main task – maintaining discipline and “order” among the prisoners. In this way, camp administrations ignored the typical crimes carried out against political prisoners: theft of private belongings, psychological harassment, physical abuse and sometimes murder.

However, the situation changed after former OUN activists and UPA fighters arrived and took control of the osoblagi. “I do not know about other places (they started killing in all the Special Camps, even the Spask camp for the sick and disabled), but in our camp [in Kengir] it began with the arrival of the Dubovka transport — mainly Western Ukrainians, OUN members,” Alexander Solzhenitsyn wrote. “The movement everywhere owed a lot to these people, and indeed it was they who set the wheels in motion. The Dubovka transport brought us the bacillus of rebellion.… These sturdy young fellows, fresh from the guerrilla trails, looked around themselves in Dubovka, were horrified by the apathy and slavery they saw, and reached for their knives…A law indeed emerged, but it was a new and surprising law: ‘You whose conscience is unclean — this night you die!’ Murders now followed one another in quicker succession than escapes in the best period. They were carried out confidently and anonymously: no one went with a bloodstained knife to give himself up; they saved themselves and their knives for another deed. At their favourite time — [in the early morning] when a single warder was unlocking huts one after another, and while nearly all the prisoners were still sleeping — the masked avengers entered a particular section, went up to a particular bunk, and unhesitatingly killed the traitor, who might be awake and howling in terror or might be still asleep.”

In the early 1950s, the camps were divided into two parts. The inmates had their own order and clearly split the territory between political prisoners and criminals. Outside the camp, the administration continued to function as before. But the situation was becoming increasingly tense: prisoners demanded changes in security, while warders wanted to restore their lost authority. For example, in order to instil order in Peshchlag (Karaganda, Kazakhstan), some 1,200 inmates from Western Ukraine who were imprisoned for anti-Soviet activity were moved to the Gorlag – a mountain mining camp. This contingent became the catalyst for the Norilsk uprising.

UNDER THE BANNER OF FREEDOM

After the death of Joseph Stalin in March 1953 and with a presentiment of amnesty, political prisoners in Soviet camps expected not merely changes but a review of criminal cases and release. Under the “Beria amnesty”, around 1 million of 2.5 million inmates were released, but this did not affect special-purpose camps for political prisoners. Outraged inmates in the Gorlag camp in Norilsk were the first to go on strike in the osoblagi. They raised the black banner of freedom that later became a symbol for other uprisings in Vorkuta (1953) and Kengir (1954).

In order to “restore order” and on instructions from Gorlag chief General Ivan Semenov, a group of criminals was moved to the 2nd camp division on 21 May 1953. They were armed with knives, and the resulting slaughter left many casualties. However, the political prisoners still refused to end their strike. On 25-26 May, armed guards twice shot at columns of inmates in the 1st, 4th and 5th divisions, killing a few and wounding many more. This is when the Norilsk uprising actually started. A week after its inception, the uprising had reached a massive scale: six camp divisions – a total of 16,379 inmates – were on strike as of 5 June. It lasted from the end of May until early August 1953.

The resistance was strictly organized: inmates formed “committees” which acted openly and regulated the duties of strikers. One person in each barrack was designated to lead the protests. These leaders made up department committees, up to 20 people in each. However, Soviet investigators found in 1956 that there were also secret groups of real organizers and leaders who were never identified. The committees were formed several days after the uprising started as a necessary form of organization. However, they acted following a clear, pre-determined plan, which led investigators to believe that they were implementing the decisions of a secret group.

Insurgents from different divisions coordinated their actions, passing information through trustworthy people, as was previously done in the OUN underground. The majority of inmates were informed about forthcoming events via leaflets. They braced for possible attacks by equipping themselves with handmade knives and clubs. Camp administration and the Soviet Interior Ministry tried to use various means (some extraordinary) to quell the uprising. Their main goal was to move the inmates out of the barracks, split them into smaller groups of 100 people each and then capture active insurgents and organizers. To this end, warders armed with clubs were sent to enter the prison territory and make arrests.

However, these attempts were thwarted by the self-defence units that inmates had formed. In order to break their resistance, camp administrators decided to resort to the field-tested practice of using groups of armed criminals. However, the rebels foresaw this move and successfully repelled the attack. According to eyewitness accounts, the criminals fled shouting to the armed guards for help: “Save us! The Banderites are killing us!”

The strike persisted, and confused party functionaries resorted to unprecedented measures: for the first time in decades they made concessions to the rebels and set up a special Interior Ministry commission headed by Colonel Mikhail Kuznetsov which came from Moscow to Norilsk on 5 June. The commission had the task of ending the strike at any cost. The camp administration arranged for a radio broadcast of the address from the commission chief intended to calm the inmates and normalize the situation. Kuznetsov assured the rebels that their demands (review of cases, cutting prison terms, cancelling special security, etc.) would be taken to the leadership of the USSR for discussion and action. Some inmates fell for the promises: rebels in the 1st division of the Gorlag reported their leaders to the administration and ended the strike.

The commission met some of the strikers’ demands regarding camp security measures and, at the same time, prepared to crush the uprising. As of early August, the uprising in the 1st, 2nd, 4th, 5th and 6th divisions had ended.

PACIFICATION WITH CONSEQUENCES

The uprising was suppressed using different measures. One was the show of force: the Gorlag administration expanded the so-called “off-limits zone” to intimidate inmates – armed guards could shoot to kill any inmates, including strikers, who crossed the line.

Some unique measures were also employed to quell the uprising: water cannons were used in the 6th division where women were kept, and firearms in the 1st division of the Gorlag. In the 6th division, the administration used fire trucks to disperse the inmates by shooting them with jets of water. Then, guards entered the territory of the camp and isolated the organizers of the strike. In the 1st division of the Gorlag, MGB troops opened fire and succeeded in capturing the camp, killing 11 inmates, seriously wounding 14 (of which 12 later died) and lightly wounding 22 more. The 3rd division held out the longest. On 4 August 1953, troops from the 4th division of military unit 7580 broke into the camp’s territory and fired upon the strikers. According to official sources, 4 were killed and 14 wounded. The unofficial count was up to 150 dead.

Even though the Gorlag uprising was eventually suppressed by the authorities, it provided the first glimmer of hope and an example of resistance in the vast Gulag system. The Norilsk events spread the virus of rebellion across the entire system. Cheka reports on the Norilsk special camp dated 17 July 1953 contain information on the suppression of uprisings in the 5th, 6th, 13th and 35th divisions. Later, a wave of large uprisings swept across the Rechlag (July 1953), Kurgansk, Unzha and Viatka camps (January 1954). Another erupted in Bodaybo in February 1954. The largest one occurred in Steplag in May-June 1954. They all ended like the Norilsk uprising but still succeeded in triggering the irreversible downfall of the Gulag system and led to its ultimate liquidation in 1960.

Notes

Osoblagi (from Russian “special-purpose camps”) were special concentration camps in the Gulag system designed to isolate political opponents that posed the greatest danger to the Soviet regime. They operated from 1948-54 and differed from general-purpose forced labour camps in their strict prison-like security and their assignment of inmates to especially difficult work in construction, mining industry, etc. A total of 12 special camps were set up in the USSR with a combined capacity of 275,000 inmates. The largest were Rechlag in Vorkuta, Ozerlag in Taishet, Berlag (popularly known as Kolyma) in Magadan, Steplag in Jezkazgan and Gorlag in Norilsk.

Gorlag (from Russian “mountain camp”; also known as “special camp No. 2”) was a special-purpose concentration camp that replaced the Norilsk Forced Labour Camp on 28 February 1948. It operated until 25 June 1954. Its inmates worked in ore mining quarries, coal mines, road construction and the Norilsk Copper Smelting Plant. As of 1 January 1953, there were 20,167 inmates in the camp. MGB Major General Ivan Semenov became chief of the Gorlag camp in 1952.

Testimonies about the Norilsk uprising

Ivan Hubka:

Ivan Hubka:

“It happened on 26 May 1953 when Diatlov, who escorted guards to the production zone in a brick plant where female inmates from division No. 6 worked, began shooting from a submachine gun at prisoners in male division No. 5. Seven of them were wounded: Klymchuk (who later died of his wounds), Medvedev, Korzhev, Nadeiko, Uvarov, Yurkevych and Kuznetsov. A submachine gun burst directed at innocent people was the last straw. At some point, without any thought of the consequences, the oppressed raises his head and declares that he is also a human being and defends his rights to life.

…The tragedy of shooting innocent inmates was framed by the administration as an accident: the escort allegedly shot at the ground, but the bullets ricocheted off of the permafrost. But it didn’t matter. The shooting was a fact, and the inmates decided to have their say. Concentration camps had no history of strikes [or uprisings] until then, because strikers would have been shot to death on the spot. (I mean in the times of Lenin and Stalin.) But here the camp administration was at a loss.”

Yevhen Hrytsiak:

Yevhen Hrytsiak:

“Indeed, our spontaneous outrage turned into a well-organized protest. The Gorlag administration was suddenly quiet. No one was shooting or even threatening us. But they decided to break us by famine. They did not deliver food to Gorstroi for days on end. In the morning of the third day, we were approached by Major General Paniukov, escorted by Lieutenant Colonel Sarychev and several senior officers. Paniukov had flown there from Kranoyarsk specifically to address this issue. Speaking in an authoritative and self-assured tone, he demanded that we resume work and promised to investigate any violations that had taken place. We refused and said we would resume work only if a government commission comes from Moscow to Norilsk… We understood that the Gulag would not tolerate this situation and would take severe measures against us. We were ready for anything, but we were not yielding our positions.”

Excerpt from a report by Mikhail Kuznetsov, chief of the Prison Department in the USSR Interior Ministry, to Deputy Interior Minister Ivan Serov:

“In late May, inmates kept in the special Gorlag camp learned about the fact that inmates from the general-purpose camps in Norilsk had begun to be released and transported by steamships under the Amnesty Decree. Some Ukrainian nationalists among them began to express their sentiments and started talking about extending the amnesty to prisoners in special camps… Later, some OUN members in the 4th and 5th divisions of the Gorlag camp provoked a large group of inmates into disobedience. They refused to come to work and then refused to eat…

Acting through our agents, we have identified the instigators of the unrest. In particular, the most active organizer is inmate Pavlyshyn, b. 1907, a Ukrainian with a teacher’s diploma from Prague University, who was convicted of high treason and organized struggle against the Soviet authorities and sentenced to 25 years. His accomplice was inmate Omelianiuk, b. 1922, a Ukrainian convicted for high treason and sentenced to 10 years. Successful measures have been taken to remove Omelianiuk from among the inmates…

Some of the Russian inmates are inclined to punish the Ukrainians who initiated the unrest. As of 3 June of this year, Ukrainian nationalists in camp divisions continue to refuse to come to work. Internal order is being strictly maintained.”