It is strange that the Ukrainian public is shocked by the treasure troves found during searches of property belonging to ministers, public prosecutors, local administration heads and their deputies. It is even more surprising that some people think millionaires only emerged after the rejection of socialism and that they did not exist in the Soviet Union, except for in comic books. It is everyone’s favourite Soviet myth– there was no corruption when Stalin was in power!

In fact, there were capitalists (of course, underground ones) during the Bolshevik era, and corruption flourished too – on a massive scale! We are not talking about the hedonists at the top of the power pyramid here, nor their hangers-on and the Cheka-NKVD-KGB mafia, but active and enterprising citizens. Since no Communist Party programme could eliminate the natural thirst for enterprise.

What could a businessman look like under Stalin? A certain Mykola Pavlenko, for example…

Beginning of the road

Here is what Russian Wikipedia has to say about him: "A fraudster, founder and commander of the mythical self-supporting organisation MCD-5 in 1942-1951, which operated in the Moldovan and Ukrainian Soviet Republics. The criminal took advantage of wartime confusion and faked documents to create a group that was disguised as a secret military construction unit." Of course, everything was much more interesting in real life: even Aleksandr Koreiko and Ostap Bender could not dream of fooling an entire empire. Mykola Pavlenko far surpassed his literary counterparts. In this sense, he was a true "Benderite".

RELATED ARTICLE: How the Bolsheviks used identity to restore the empire

Pavlenko was born in 1912 in the village of Novi Sokoly, Kyiv Oblast. He was the seventh child in a wealthy miller’s family, which was doomed from the very beginning of the collectivisation process. Mykola left home at 16, shortly before the family were "dekulakised" and sent to Siberia (no one returned).

He forged new identity documents, giving himself an extra four years of age and a more appropriate social background. He enrolled at the Kiev Civil Engineering Institute (or, according to other sources, Minsk Polytechnic). The young lad always dreamed of becoming a builder: he wanted to build roads – a symbol of faraway uncharted territory for peasants, who were firmly rooted to their land.

Pavlenko was an outstanding student and started to believe that he had gotaway with it, would be able to quietly graduate, integrate into Soviet society and do the thing he loved the most. These illusions lasted for two years.

The regime needed new sacrificial offerings and the search for "enemies of the people" was gaining momentum. Personal files of teachers and students began to be checked at the institute where Pavlenko was studying. Realising it was only a matter of time before he would be exposed as a kulak's son, Mykola disappeared.

And became an ordinary worker: he went to build roads. Even this did not save him, and in 1935 Mykola was arrested in the city of Yefremov, Tula Region, Russia under the decree "On protecting the property of state enterprises, kolkhozes and cooperatives, and strengthening public (socialist) property" from the USSR Central Executive Committee and Council of People's Commissars dated 7 August 1932 (the so-called "seven eighths" law). After spending 35 days in remand, realising that things were bad and he had to find a way to survive, Pavlenko did not put up any resistance and allowed NKVD agents Sakhno and Kerzon to recruit him as a secret informer.

It is obvious that Pavlenko's natural insight, sharpness and intuition came in very handy for this sort of work, because Sakhno and Kerzon soon recommended him as a "conscientious" and "loyal" member of staff for the position of construction manager at the Chief Army Construction Department (CACD). There, Pavlenko rapidly carved out a career for himself and was promoted to head of his construction district (in Minsk). Moreover, he was already being looked at for a job at the central office.

This is when Pavlenko formed his modus operandi, and also when he read Ilf and Petrov's book The Golden Calf, which made a lasting impression on him. The Minsk Construction District worked quickly and efficiently, and – most importantly – very economically. This was incredible in a socialist economy, where everything was stolen: by producing substandard materials, simplifying production techniques and not worrying about worker safety. At first, Pavlenko also looked to cash in on the imperfections of the system, but his approach was fundamentally different. His savings scheme significantly reduced costs, and spare building materials were sold on the side: who can you blame for the fact it was dangerous to have entrepreneurial talent during Soviet times?

RELATED ARTICLE: Baltic jazz in Soviet times

Mykola again thought he could finally get on with quietly doing what he loved – building roads. But then war broke out.

The roads of war

On 27 June 1941, assistant engineer of the 2ndInfantry Corps, first-rank military technician and Senior Lieutenant Mykola Pavlenko left to join his unit at the front. The corps suffered huge losses and retreated to the town of Vyazma. Pavlenko had no desire to fight and die for the system that had deprived him of his home, family and future, and which could offer him nothing but the chance to be repressed and die like cattle or cannon fodder for the empire.

So in September, forging an assignment notice and assigning himself the rank of Captain, Pavlenko raced away from the front in a truck full of stolen canned meat with a personal driver behind the wheel. Arriving in the rear, he found acquaintances from his pre-war life, who had also deserted, in Kalinin (now Tver). This was not difficult, because an entire network of deserters with its own contacts and sources of funding operated in the front-line city. The NKVD periodically raided their secret rendezvous, but there were many ex-soldiers in town who had gone AWOL and their number increased daily as more Soviet units were routed.

The men had everything they needed to lie low for a reasonably long time: Pavlenko had his meat and a fellow Ukrainian, Ludwig Rudnichenko, had a virtuoso talent for counterfeiting documents. Ludwig greatly impressed his colleagues when before their very eyes he cut the words "Kalinin Military Commissariat" out of the sole of a soldier's boot to make a stamp. That is how they provided themselves with documents that solved their housing, food and security problems.

Some people, perhaps, would be satisfied with this, but not Pavlenko. He decided that having such opportunities and using them in such a limited way was simply ridiculous. He suggested to his flabbergasted comrades that they stop hiding and go into real business.To be more specific, by creating a military construction organisation.

Why construction? Because a scheme will not last for long if it only exists on paper. And what did Pavlenko know how to do well? Correct, build roads! It was a favourable time for fraud: there was complete disorder at the front and in the rear after the summer defeats – no one had any idea which units were still around. The main instrument of law and power was a piece of paper with the right stamp and a prudently offered bribe. Therefore, provided the documents were done properly, it would be extremely difficult for the NKVD to expose the swindle.

They called their organisation Military Construction District №5 (MCD-5). Pavlenko was "unit commander" and "third-rank military engineer" (equivalent to an army major). Rudnichenko would take care of the paperwork, and another accomplice, Yuri Konstantinov (aka Konstantiner) was entrusted with security.

Having used forged ration cards to get their hands on more canned meat and condensed milk, the freshly minted builders visited the local printing house. The necessary stationery was quickly prepared in exchange for these groceries and Military Construction District №5 became a legitimate organisation. Not just that – the counterfeit documents allowed them to open an account at the Kalinin branch of the State Bank and get some uniformsfrom clothing depotsthat corresponded to their military branch and invented ranks.

After some "cordial" conversations with the local military commissar and commander, Pavlenko gained the right to recruit category G servicemen (the wounded who were being treated) into his unit. Shortly after, the number of personnel reached 40, promptly reinforced by deserters and soldiers left behind by their subdivisions. The equipment issue was easily resolved too: they simply collected the trucks, excavators and bulldozers that were abandoned at the roadside during the retreat.

The newly formed military unit got down to work. Pavlenko concluded contracts for road building and construction work with various organisations in Kalinin. They operated quickly and efficiently, earning good money, paying wages punctually and dividing profits between the "shareholders". Subsequently, Pavlenko introduced cash bonuses and the soldiers, accustomed to menial labourer status and miserable pay in rations, responded with an explosion in workplace enthusiasm.

The "business" grew quickly: the quality offered by MCD-5 stood out too much compared to the work done by other units. Everything was set up seriously: there was an "officer corps" personally loyal to Pavlenko, a Counterintelligence Service under the command of Konstantiner and – most importantly – the soldiers did not even suspect that they were serving in a non-existent unit!

All this continued for a year, until the Kalinin Front army formation was disbanded in autumn 1942. It made no sense for Pavlenko to stay in the rear, where there was more supervision and less work. They had to follow the front line, which was moving towards the west.

Pavlenko had a good reputation and considerable resources, so easily found a new home – the 12thAviation Base District. Thanks to a bribe, it was possible to ensure not only full pay for his construction unit, but also the necessary cover for following the Red Army.

RELATED ARTICLE: The history of Kharkiv

All this time Mykola did what he loved the most – built roads. Satisfied customers recommended him to their friends and colleagues, so the "business" grew in leaps and bounds. By the time they reached the Soviet border, Pavlenko's construction unit had two hundred employees and a brilliant track record, while the earnings of the "shareholders" amounted to one million roubles. How did Pavlenko manage to pull this off under Stalin's system of total control and accountability? Even amidst the confusion of wartime? Either he was fantastically lucky. Or…

Or his contacts with the NKVD did not end when the war started. Military road-building organisations were subordinate to not only the Ministry of Defence, but also the NKVD. This had been established practice since the 1930s, when construction bureaus were manned with prisoners and worked on the "Great Construction Projects of Communism". So we can assume that a financially successful organisation could not possibly exist without catching the all-seeing eye of the people in blue-topped caps. It is quite likely that Pavlenko had protection within the NKVD, in return for which he passed kickbacks up the chain of command – a principle that modern Ukrainians are all too familiar with. All he had to do was work well and not get into trouble. Which is exactly what he did. Enriching himself and his invisible patrons.

The road to Berlin

But the real feast for the "clandestine capitalists" of the Stalinist regime started in Europe. Officially, they built bridges, roads and airfields, getting nothing but words of thanks from commanders in return.

However, Pavlenko did not only build things in the wake of Soviet forward units, but also earned money in another way. His men entered the empty Polish and German cities and… scooped up war trophies – both abandoned equipment and the property of the "liberated" population: cars, tractors, bicycles, carpets, sewing machines, gramophones, accordions, livestock, fodder, building materials, gold, jewels, works of art… By the time they made it to Berlin, their income exceeded that paltry first million many times over.

Interestingly, Pavlenko had his principles in the "trophy business" too: it was forbidden to touch anything that had owners (or the owners themselves). Once, he even shot three of his men dead for violating this ban. Although it was of course difficult for him to have full control over his subordinates in such a situation.

Pavlenko made his way to Berlin in comfort, alongside his wife, whom he met in Kalinin. Arriving in the German capital, he realised that he had hit the jackpot: thanks to bribes, Chief Logistics Command instructed him to collect captured enemy equipment. He sold some of the "harvest" and made an agreement with representatives of the Ammunition and Transport Supply Department and people from the military commandant's office to be allocated an entire train of 30 carriages to take the rest back home. The "shareholders" earned another 3 million roubles.

Back in Kalinin, Pavlenko decided to disband his unit in April 1946: the war was over and inspections were toughened, so the underground millionaire did not see the point in taking any more risks.

Personnel who had no idea about the true status of the organisation were demobilised first. At a ceremony, Pavlenko presented his men with orders and medals (a total of 230) that he acquired thanks to a fake report and a large bribe, as well as cash bonuses for their strong work ethic: 7-12 thousand roubles for soldiers, 15-25 thousand for officers. Pavlenko did not forget himself either: he picked up a 1st and 2ndClass Order of the Patriotic War, Order of the Red Banner, Order of the Red Star and 90,000 roubles.

Roads of peace

After the war, he took charge of a civil road construction company in Kalinin – Plandorstroy. It seemed the future would be rather serene: he had finally found his safe haven. Mykola Pavlenko had a wife and young daughter, and planned to live in the lap of luxury: they had their own houses in Kalinin and, of course, Ukraine. As well as cars (the fine Pobeda model, obviously) and other trappings of the high life for those who were not threatened by the Ukrainian famine of 1946-1947 or deportation to Siberia.

This happy ending only lasted two years. The situation in the country was changing. A new witch-hunt began and people started to be examined more intently, while Mykola Pavlenko's nest egg unexpectedly plummeted in value following the 1947 currency reform. He felt the urgent need to relocate and return to his favourite occupation. He stole all the cash from the Plandorstroy coffers (339,326 roubles) and moved south with his wife and daughter.

RELATED ARTICLE: The history of Odesa

In Ukraine

In the Soviet Union of 1948, there was only one restless region with weak state control – Western Ukraine, where Banderite rebels did not stop their fight despite the “victory of the Soviet people”. Pavlenko arrived in Lviv, had a look around, got in touch with Konstantiner, Rudnichenko and the rest of the "shareholders", and the wheels of their machine were set in motion again. In Lviv, the "builders" created a new "Military Construction Administration" (MCA-1). Following their tried-and-tested scheme, they produced the necessary documents, recruited men, obtained equipment and set to work. The initial conditions were excellent: the "shareholders" had considerable underground business experience and Pavlenko looked rather dignified in the role of decorated war veteran. Most effective were hints that MCA-1 was carrying out secret missions for the NKVD (this gambit worked well before, and it was flawless in post-war Western Ukraine, which was teeming with special agents and informers).

Pavlenko really did collaborate with the Ministry of State Security: local security agencies selected personnel for MCA-1 and provided them with weapons for "protection against Banderites". In "liberated" Ukraine, MCA-1 did not stand out from the crowd of Soviet military units with its daily routine, combat and political training, patrols and flag.

The new "business" expanded rapidly. Within four years, it was a huge structure with headquarters in Chisinau and branches in Ukraine, Belarus, Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia. More than three hundred people (military and civilian) worked for the "firm", which built mining, machine-building, food production and winemaking facilities in six Soviet republics.

From a modern perspective, Pavlenko was just a successful businessman who honourably fulfilled the contracts he entered into: bridges, roads and buildings were constructed on time and to high standards. His methods were market-driven: workers and engineers were paid well, depending on results, while dedicated workhorses were sometimes rewarded with a barrel of beer at the end of their shift. As for the bribes… well, a backhander to an official is a valuable entrepreneurial tool in adverse conditions for doing business.

Pavlenko was not a revolutionary and, indeed, not an ideological enemy of the system. Despite his hatred for the Soviets, he did not make a conscious stand against them. He was a simple entrepreneur who lived as far away from the system as possible and just did his job. As he later said himself, "We did not conduct not anti-Soviet activities, we simply built things as well as we could, and we were good at it." During those four years in Ukraine, MCA-1 concluded 64 contracts worth a total of 38,717,600 roubles. The "shareholders" were making such large amounts that their spoils of war from Germany seemed like small beer.

Mykola Pavlenko, an imposing and confident colonel (he conferred this rank upon himself in 1951), had influence in local government and was invariably sat next to the presidium at all official events. As before, he personally supervised major projects: it was the only way to ensure the quality that had become the hallmark of MCA-1.

RELATED ARTICLE:The Rise and Fall of Russian Wannbes

It seemed that Mykola Pavlenko had become a person of national, rather than regional, significance in Ukraine, and he again began to think that he could strike a balance in life and quietly reach old age.

However, the larger an organisation becomes, the more difficult it is to control. Endless success created a sense of impunity in his closest partners, who were, to put it mildly, not the most decent of people. Over time, more and more slip-ups occurred: one of the "shareholders" would get drunk and start a fight in a restaurant or run someone over in their car, so Pavlenko would have to persuade the police to release him; once, a drunk Konstantiner dropped 2 million roubles, which he was taking to their high-ranking patrons, on an airport runway – much of this sum was lost as hush-money. Another time, Ludwig Rudnichenko, persuaded by his wife, decided to demand money from Pavlenko, threatening to turn in the entire "firm". Rudnichenko ended up with 17 days under arrest, but Pavlenko later gave him 25,000 roubles anyway.

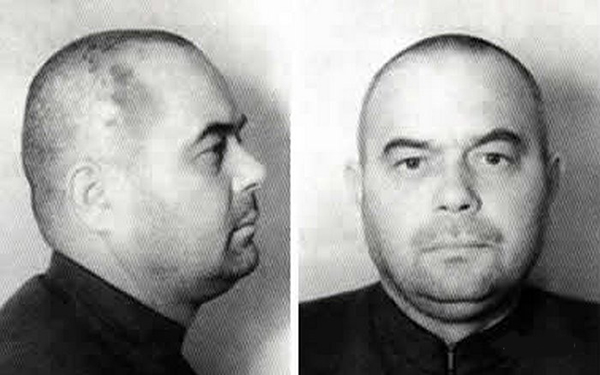

Mykola Pavlenko: A master of turning soviet construction brigades into profitable firms

These careless members of Pavlenko's inner circle were never severely punished, the level of discipline in the unit started to fall, and it was only a matter of time before the entire house of mercantile cards came crashing down. It is unlikely that Pavlenko,with his exceptional intuition,did not realise this. But he was probably unable to leave his work behind once again and try to restart from scratch somewhere else. MCA-1 was a substitute family for the one that the Soviets had taken away from him in 1928 – he would not be able to go through that sort of loss again.

Pavlenko's "protection" continued to hold up, covering him against such slip-ups. But sooner or later something inevitably had to go so wrong that there would be no way out, and it would affect the entire "firm" – so much that it attracted the attention of the very top of the Soviet system.

In the gutter

That is what happened. A stupid, but typical detail ruined Mykola Pavlenko and his "underground business". Since MCA-1 positioned itself as a normal Soviet military unit, it, like the others, was supposed to distribute government bondson a voluntary/compulsory basis. And because MCA-1 could not get them legally, they had to be bought on the Lviv black market. Once, an officer got greedy and decided to keep some of the money meant for such a deal. As a result, one of the civilian workers – a certain Party member called Yefimenko – was issued with bonds worth a smaller amount than he was owed. Yefimenko dashed off a complaint to Marshal Voroshilov, informing him that Colonel Pavlenko was not only disrupting a matter of national importance (the bond campaign), but also hired escaped prisoners and former Nazi collaborators.

An order was given to prosecutors in the Carpathian Military District to investigate and a criminal case was opened in Lviv on 23 October 1952. By 5 November it had been transferred to the Chief Military Prosecutor's Office. What a surprise it was for the authorities when it became clear that the military unit MCA-1 does not really exist! This colossal structure with branches in six republics, hundreds of people, tons of equipment, two dozen bank accounts, a turnover of millions and a huge number of completed projects was a hoax, no traces of which could be found in any database at the Ministry of Defence or other government agencies.

It emerged that Pavlenko had been on the nationwide wanted list since the Plandorstroy incident in 1948. Now these two cases were consolidated into one.

There was shock in Moscow: in the strict police state that was Stalin's Soviet Union, there had been a huge illicit military structure that made millions for years on end thanks to the illegal labour of Red Army servicemen! And worst of all – it was a capitalist structure! Which functioned perfectly in the very heart of the socialist system!

The operation to eliminate MCA-1 was conducted simultaneously in six republics. On 14 November 1952, 50 officers and 300 privates were arrested and more than 100 firearms, almost 70 vehicles and construction equipment were seized, as well as a huge number of seals, stamps and letterheads.

On 23 November, Mykola Pavlenko himself was arrested too. Order №97 for his arrest was signed by the Deputy Minister of State Security for the Moldavian SSR, Lieutenant Colonel Semyon Tsvigun. An interesting nuance: epaulettes for a General were found at Pavlenko's home during his arrest.

Prominent representatives of the republic's establishment were found to be involved in the MCA-1 case, such as Moldovan Food Industry Minister Tsurkan and his deputies, First Secretary of the Tiraspol Party Committee Lykhvar, Secretary of the Bălţi Party Committee Rachynskyi, several Prombank managers, directors of state enterprises, commanders of military units and so on. Nevertheless, it is obvious that Pavlenko's most senior "contacts" avoided responsibility.

A special team of experienced investigators, headed by V. Markalyanets and L. Lavrentyev, was created by the Chief Military Prosecutor. They had quite a bit of work to do: over two and a half years, they collected 164 bundles of evidence.

RELATED ARTICLE: Former UPA fighter shares his story of struggle

Above all, the investigators were amazed that Pavlenko was paid for work that was actually carried out – and better than others could do it, at that. Alexander Lyadov, a senior investigator at the Central Railway District who worked on Pavlenko's case, remembered it as follows: "He built well. He brought in outside experts under contract. Paid wages in cash that were three to four times higher than at state-owned enterprises. He checked the quality of work himself. If he found any shortcomings, he wouldn't leave until they were fixed. After the first test of a completed line, he would put out a few barrels of beer and snacks for his workers free of charge, then personally give the engine driver and his assistant a bonus, right there in front of everyone. At that time, many workers were getting 300-500 roubles a month. […] But I didn't tell anyone about it. They wouldn't have believed me anyway."

End of the road

The trial began on 10 November 1954. The judges took turns to read out the indictment over several days. Pavlenko and 16 of his closest associates were charged on three counts: undermining state industry through the corresponding use of state enterprises, anti-Soviet agitation and participation in a counterrevolutionary organisation. Pavlenko admitted his economic crimes, but declared he "never had the goal of creating an anti-Soviet organisation".

Incredibly, he was acquitted of this charge – the rest was already enough. On 4 April 1955, the verdict was announced: Pavlenko was found guilty on multiple counts under Article 58-7 of the RSFSR Criminal Code and was sentenced to the maximum penalty (execution by firing squad), while 16 of his colleagues – Rudnichenko, Konstantiner and others – were sent to prison for terms ranging from 5 to 20 years, in addition to the restriction of their rights, confiscation of their property and revocation of their government awards. The verdict was final and not subject to appeal.

Party and government functionaries found to have ties with Pavlenko were punished in various ways: court hearings, dismissal, exclusion from the partyand reprimands.

Brezhnev himself was in great danger, but he was very lucky that his close friend Tsvigun was working on the case. Tsvigun did everything he could to take the heat off Brezhnev, which was extremely risky, as a campaign against the misuse of authority by senior government officials was taking place at the same time in Moscow on Stalin's instruction. The Leader was planning yet another purge (this time based on economic criteria) and Brezhnev, accused of having links with Pavlenko, would have looked great in the dock. After all, over two years as first secretary of the Communist Party of Moldova he failed to prevent the "anti-Soviet armed organisation MCA", as it was called in military prosecutor documents, from operating in the republic. Tsvigun saved Brezhnev, although he was demoted to deputy head of the army's Chief Political Directorate.

Pavlenko was less lucky. He was executed by firing squad shortly after the verdict. He was 43. History repeated itself in a strange way: his parents' family had been stripped of everything and sent to Siberia, and now his wife and daughter had their property confiscated and were exiled to the same place as family members of an "enemy of the people".

Translated by Jonathan Reilly

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook