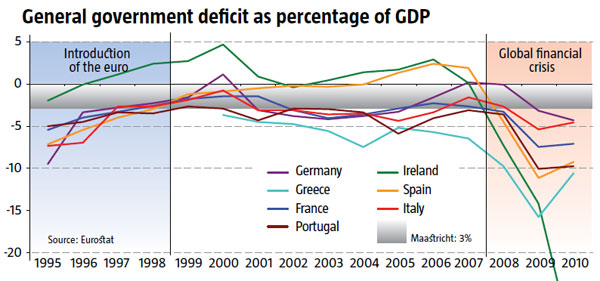

The commonly-heard story is that governments were responsible – they borrowed and spent too much during the good years after the euro’s inception in 1999. Then the financial crisis arrived in 2007-08, causing these governments’ debts to become unsustainable. In the case of Greece, this is a fairly accurate picture. But in the case of the rest of the eurozone, it conflicts with the data. For example, the Spanish and Irish governments actually ran sizable budget surpluses during the middle of the last decade. Meanwhile the German government was a major borrower – it was among the first governments to break the 3% Maastricht criterion (later enshrined in the Growth and Stability Pact), and went on to break the rules for five consecutive years.

Despite Germany’s misbehaviour, once the financial crisis arrived, German government debt was treated by markets as a safe haven. And despite Spanish and Irish prudence, both countries have fallen into the “PIIGS” camp of governments to whom markets are nervous or outright unwilling to lend. It seems that the fiscal rules in the Stability Pact were of little value in averting the crisis. Markets have instead focused on the deep recessions and government deficits that arose in Spain and Ireland after 2008, and show little interest in their earlier prudence.

But if it wasn’t excessive government borrowing, what did cause the crisis?

Here’s what: In the run up to the creation of the euro, interest rates in the PIIGS countries steadily fell to the same level as Germany. Markets anticipated the elimination of currency risks and differentials between the various eurozone members. Markets also assumed that each government within the euro would be as creditworthy as the next. All of which meant that borrowing costs for PIIGS governments were practically the same as for Germany for almost 10 years until the 2008 crisis.

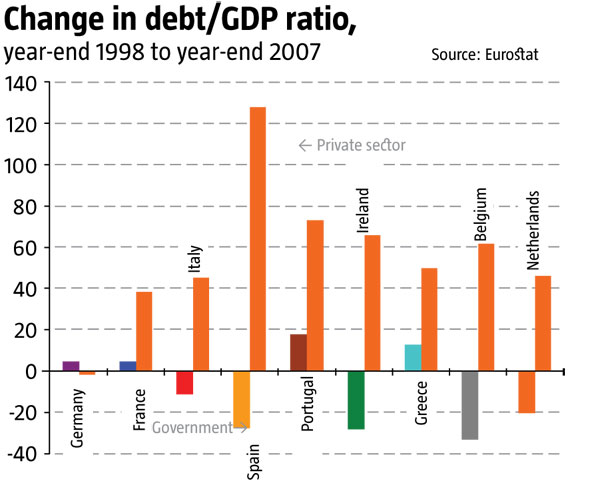

But despite the temptation of cheap debt, governments behaved themselves. In Italy, Spain and Ireland, government debt-to-GDP ratios actually fell in 1999-2007. Only in Greece and Portugal did government debts rise noticeably. However, what was much more significant during this period was the accumulation of debts by the private sector – by households and non-financial corporations. In Spain, the most extreme example, private sector debts rose by 120 percentage points of GDP during the boom years, to more than double GDP by the eve of the 2008 financial meltdown. Only in Germany was a build-up of private sector debts notably absent.

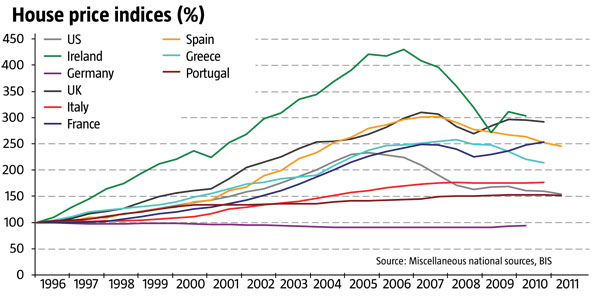

Much of that private sector debt accumulation was driven by property bubbles, similar to those seen in the US and UK. At their pre-crisis peaks, house prices had quadrupled in Ireland, tripled in Spain and risen two-and-a-half-fold in many other European countries, including France. European house prices have yet to fall by anywhere near as much as in the US. Rising house prices were accompanied by a build-up of mortgage debts and loans to finance speculative construction. Again, Germany was the major exception – house prices in 2010 still remained slightly below their levels of the mid-90s. There was no German housing bubble.

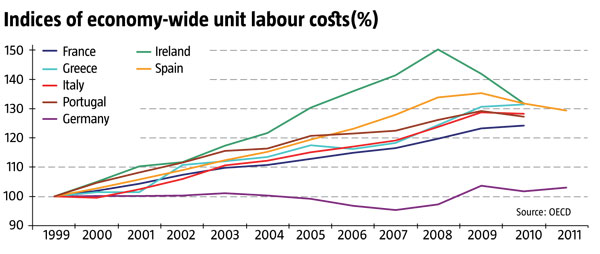

Unfortunately, debt accumulation and property bubbles are only half the story in the PIIGS countries. During the good years before 2008, these countries also experienced substantial rises in labour costs. High levels of borrowing and spending stimulated growth and kept unemployment low. This encouraged higher wage demands by unions in the PIIGS countries. Pay rises outstripped increases in productivity in these countries. Meanwhile, in Germany the “Hartz” labour reforms and a series of national pay agreements between unions, industry and the government helped to hold down German wage costs.

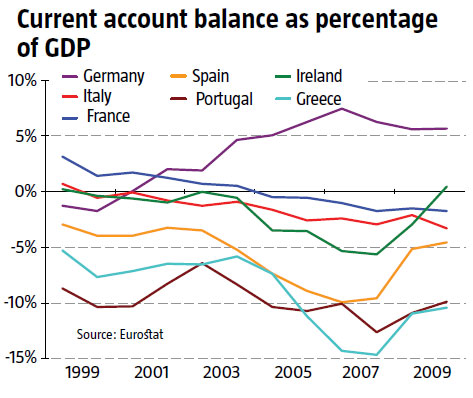

As a result, German workers have gained a massive competitive price advantage over other workers inside the eurozone. This has been reflected in a growing current account surplus in Germany – and current account deficits in other eurozone countries. Because of their competitive advantage, Germans have sold and earned more than they spend. The flipside is that PIIGS countries have bought and spent more than they have earned. Since the crisis began, it has been very hard for the deficit countries to regain wage competitiveness against the Germans. They cannot devalue their currency. And it is also very hard to co-ordinate wage cuts across their economies, even though unemployment is now very high in the PIIGS countries. They are stuck with over-priced workers in an overvalued currency, while Germany enjoys exactly the opposite conditions. The Greek economy for example is still spending 10% more than it earns, despite four years of recession brought on by massive private sector and public sector spending cuts.

Historically, the PIIGS economies were able to run currency account deficits – in other words overspend – because their banks could borrow the difference. In effect, the German banks recycled the enormous surpluses earned by the German economy by lending them to the PIIGS banks. But since 2008, and particularly since 2010, European banks have been unwilling to lend to each other. Fears have grown that PIIGS banks face enormous losses – more than can be absorbed by their capital reserves, and more than perhaps even the PIIGS governments can absorb. What is more, there are fears that PIIGS countries may leave the euro and devalue their newly-recreated currencies, in which case any loans provided to these countries would become unrepayable in euros.

The resulting banking crisis in the eurozone has shown up in a ballooning of the ECB’s balance sheet. Banks are no longer willing to lend to each other, so the ECB has in effect acted as a safe intermediary, providing emergency loans to and taking excess deposits from the banks. Over time, the general direction of lending within the eurozone – i.e. from surplus countries like Germany and the Netherlands, to deficit countries like the PIIGS and France – has also shown up in the ECB’s balance sheet. As of February, Germany’s central bank – the Bundesbank – was lending 550bn euros to the other national central banks of the eurozone via the ECB. The Bundesbank is increasingly exposed to losses if a country like Greece exits the eurozone along with its central bank. This lending by the Bundesbank is doing more than just replacing private-sector bank loans. It is also enabling capital flight from the PIIGS countries. In Greece, household and corporate deposits have fallen 30% since late 2009, as ordinary Greeks fear their country may leave the euro.

Although financial market stress has fallen significantly since Mario Draghi unveiled the ECB’s “back-door” bailout of PIIGS banks via three-year loans late last year, the underlying problems of the eurozone – excessive debts, government deficits, excessive labour costs, trade imbalances, political divisiveness – have not gone away. The eurozone faces a number of serious dilemmas that have yet to be solved:

Borrowers vs Lenders: Are debts repayable, and if not, who will take the loss? The focus has now shifted away from the Greek government towards Portuguese government debts and Spanish mortgage debt.

Austerity vs Growth: Can households, banks and governments all cut their debts at the same time without plunging the economy into a deep recession? Should government austerity be postponed until household austerity is complete? Should Germany do more to help by increasing its government spending?

Importers vs Exporters: How will the PIIGS regain competitiveness without cutting wages? If they cut wages, how will households repay their debts? Should German wages rise more quickly, in order to erode Germany’s wage competitiveness? If so, will this not conflict with the ECB’s inflation mandate?

Solidarity vs Discipline: How much financial support should eurozone members give each other? Should Germany just provide loans, or give direct fiscal transfers – e.g. via Europe-wide unemployment insurance or bank insurance? Should Germany invest in the infrastructure of the PIIGS? How can Germany do this while avoiding the creation of a dependency culture among the PIIGS, like in eastern Germany or the south of Italy?

Europevs the Nations: Does the EU have the legitimacy to provide a long-term, centralised solution to the eurozone’s problems? Is there anyone who can credibly advocate a common European solution to the crisis? If European democratic institutions are strengthened to support legitimacy – e.g. by making the European Commission President directly elected – how would non-euro countries like the UK fit into this framework?

Markets vs Voters: Are financial markets confident that politicians have the determination and the support of voters needed to solve the eurozone’s many problems? If markets begin to doubt that there is a solution that is both financially workable and acceptable to voters, the crisis could well intensify again.

How does all this affect Ukraine? There are three possible channels:

1) Direct economic impact: The euro may continue to weaken in currency markets. A weaker euro would help the eurozone as a whole run a current account surplus with the rest of the world. Ukraine’s trade with the eurozone is 20% of its GDP, meaning it is very exposed to a more competitive euro. What’s more, Ukraine would be exposed to a period of sustained low growth in the EU (assuming Eastern Europe suffers stagnation along with the eurozone). Exports to the EU are 11% of Ukraine’s GDP. The EU has also been a major provider of FDI to Ukraine in recent years – 4.5% of Ukraine’s GDP last year, more than enough to finance Ukraine’s own 2% current account deficit.

2) Financial exposure: Ukraine has direct exposures to the eurozone banking system. Eurozone banks may cut back on their international lending as they are forced to improve their capital adequacy ratios. They may also lean on Ukrainian banks they own to provide them with capital and liquidity, and to cut back their own lending. Raiffeisen, Unicredit, BNP and Hungary’s OTP all have a presence in Ukraine. Finally – as Ukrainians will no doubt be familiar – a general rise in risk aversion by financial markets will make it harder and more expensive for Ukrainians, including the government, to borrow and attract investment. In this respect, Ukraine is helped by its limited capital controls, which should limit the impact of hot money inflows and outflows.

3) Political fallout: Economic stagnation and internal wrangling in the EU are likely to weaken the EU’s position internationally. This is particularly true in respect of Ukraine, which is still considered a possible accession country. EU accession may become less attractive and much more distant prospect – particularly if the EU itself enters a prolonged period of “naval gazing” as it tries to fix the many problems in the eurozone. This will weaken incentives for Ukrainian politicians to implement the reforms needed to enable accession – reforms that are of themselves of long-term benefit to the country – and instead implement policies that bolster their own political position and the interests of their supporters.