“A swan soul”

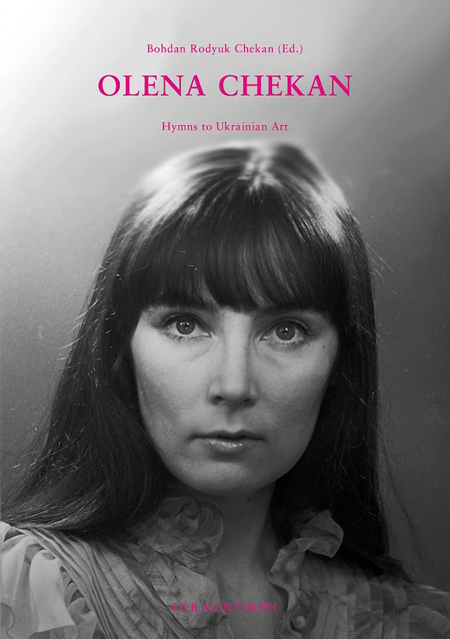

Olena Chekan worked at The Ukrainian Week publication since the beginning, when this magazine was born. She herself made it absolutely new and unique, and it remains unique today as well. Olena Chekan always walked her own path in journalism. Intellectual and culturological journalism, marked with the unique personality of an author, recognizable style, impressionistic mood and some bright and warm life philosophy, is still rare in our terrain. This is actually a secret of journalistic expertise, when a journalist becomes a writer. This woman entered your room or came to your life, and everything became brighter. She was an actress, a reciter and a journalist, and these were her three incarnations that cooperated and interacted with each other, empowering hidden resources. Hence the rare range of her journalistic experience. Olena liked Marina Tsvetaeva very much and recited her poetry in a unique and elegant way. She recited it the way the eternally young lady in Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris, performed by Olena Chekan, could do it. A woman, who looked silently through the window and saw the open Space. That is why this aristocratic twilight, where Olena Chekan recited Marina Tsvetaeva and other great Russian poets and writers, silently and without pathos, becomes so important amid the current events and dramatic developments, when Ukraine and Russia met in their battle on the tectonic fault of the history, when the borders of New Europe are being reshaped,  when Russian music, art, poetry and culture fell into the lumiere of Putin’s Russia as if it all never existed. It is one of the faces of real Ukraine: to meet disgusting violence of an Empire with the calm voice of culture and dignity. I would like to remember Mrs. Olena with the bright and warm memory flashes. We were practically neighbors with her, as she lived close to our house. There was a pine there. Mrs. Olena showed it to me with incredible joy during one of our first meetings. Something happened to that pine, it was touched by the poisoned wind or something like that, so its top started to shrink and its needles bent to and fro. Olena said she talked to that pine, she prayed for it, she sent it positive fluids… And then suddenly the pine came back to life, its needles started vibrating lightly and its top turned lively and green again. This woman expressed wonder of life. Really, she was always like a charmed elf that despite all the troubles of life and time pressure in this world looked happily and always saw the green world, heard the music of trees, felt the living soul in everything around, brought hope, joy and happiness to everything. We once met in the street. It was our last meeting when she was still healthy. It was snowing, and Olena lightly walked down the streets, dressed in an elegant fur coat, glimmering in the light of the street lanterns. She told me about her life. She told me about a beautiful and tragic story and about a woman’s sacrifice. She told about mystic of love. I even suggested she’d write a story about this, as beside the very talented and excellent articles, interviews and reports, Olena also wrote great impressionistic essays. You could read them on the last page of The Ukrainian Week, after the important and serious issues, and it felt as if you came to visit her in the evening and to sit together at the fireplace, sharing some secret signs with a tree or with a child. Mrs. Olena was a real magician of such essays, and one could see her great potential as a talented writer of prose. She described me the story of her interesting and difficult life in the same impressionistic manner. It seemed that she wanted to hand her secret of a great feeling to somebody she trusted. Then, when we said good-bye to each other and parted, I followed her with my eyes, looking how she faded away into the snow as if drawing a light veil of evening snowflakes behind herself. And here is one more episode. It was Independence Day, August 24th, when Viktor Yanukovych had already grasped fitfully the power and the state. Mrs. Olena called me to congratulate on the occasion, she was going to go to Maidan. And she told me with energy and joyful passion of a teenage girl: I will wear my vyshavanka (embroidered shirt – Ed.) out of principle. And it seems she really had an antique and beautiful embroidered shirt with the deep colors. Here is one more flash. During one of our meetings at The Ukrainian Week we spoke about an importance of the articles and materials on academic hypotheses and discoveries concerning position and conditions of a human being in the modern world. I remembered the theory of Italian scholars from Parma about mirror neurons, the mysterious cells that are activated when one starts observing behavior of another human. With the help of those neurons people can decrypt actions and feelings of other people, learn to understand them, turn these symbols into language and build system of coordinates in order to orientate not only in space and time, but also in ethical fields. When another person suffers, our mirror neurons force us to put ourselves into this person’s place, turning in our empathy, sympathy and compassion. Thus, this neuro-physiological phenomenon speaks for the natural imperative for the human civilization survival, and it takes shape in compassion, remorse, empathy. In bio-social behavior of people this is named “empathic complicity”. It’s the reason for solidarity, mutual support and help. Social responsibility is programmed inside of us on the biological level. Later, a person turns this instinct into music, poetic word or a prayer. Light and beautiful April soul left this world in cold December 2013. Olena saw the beginning of Euromaidan one month before her death. Maybe it was easier for her soul, made from poetry, music and flowers, to leave this worlds seeing Ukraine as she started releasing from the hold of the Kremlin horror… I don’t know, maybe God sent the “hawks’ night” after her. But I know that she go

when Russian music, art, poetry and culture fell into the lumiere of Putin’s Russia as if it all never existed. It is one of the faces of real Ukraine: to meet disgusting violence of an Empire with the calm voice of culture and dignity. I would like to remember Mrs. Olena with the bright and warm memory flashes. We were practically neighbors with her, as she lived close to our house. There was a pine there. Mrs. Olena showed it to me with incredible joy during one of our first meetings. Something happened to that pine, it was touched by the poisoned wind or something like that, so its top started to shrink and its needles bent to and fro. Olena said she talked to that pine, she prayed for it, she sent it positive fluids… And then suddenly the pine came back to life, its needles started vibrating lightly and its top turned lively and green again. This woman expressed wonder of life. Really, she was always like a charmed elf that despite all the troubles of life and time pressure in this world looked happily and always saw the green world, heard the music of trees, felt the living soul in everything around, brought hope, joy and happiness to everything. We once met in the street. It was our last meeting when she was still healthy. It was snowing, and Olena lightly walked down the streets, dressed in an elegant fur coat, glimmering in the light of the street lanterns. She told me about her life. She told me about a beautiful and tragic story and about a woman’s sacrifice. She told about mystic of love. I even suggested she’d write a story about this, as beside the very talented and excellent articles, interviews and reports, Olena also wrote great impressionistic essays. You could read them on the last page of The Ukrainian Week, after the important and serious issues, and it felt as if you came to visit her in the evening and to sit together at the fireplace, sharing some secret signs with a tree or with a child. Mrs. Olena was a real magician of such essays, and one could see her great potential as a talented writer of prose. She described me the story of her interesting and difficult life in the same impressionistic manner. It seemed that she wanted to hand her secret of a great feeling to somebody she trusted. Then, when we said good-bye to each other and parted, I followed her with my eyes, looking how she faded away into the snow as if drawing a light veil of evening snowflakes behind herself. And here is one more episode. It was Independence Day, August 24th, when Viktor Yanukovych had already grasped fitfully the power and the state. Mrs. Olena called me to congratulate on the occasion, she was going to go to Maidan. And she told me with energy and joyful passion of a teenage girl: I will wear my vyshavanka (embroidered shirt – Ed.) out of principle. And it seems she really had an antique and beautiful embroidered shirt with the deep colors. Here is one more flash. During one of our meetings at The Ukrainian Week we spoke about an importance of the articles and materials on academic hypotheses and discoveries concerning position and conditions of a human being in the modern world. I remembered the theory of Italian scholars from Parma about mirror neurons, the mysterious cells that are activated when one starts observing behavior of another human. With the help of those neurons people can decrypt actions and feelings of other people, learn to understand them, turn these symbols into language and build system of coordinates in order to orientate not only in space and time, but also in ethical fields. When another person suffers, our mirror neurons force us to put ourselves into this person’s place, turning in our empathy, sympathy and compassion. Thus, this neuro-physiological phenomenon speaks for the natural imperative for the human civilization survival, and it takes shape in compassion, remorse, empathy. In bio-social behavior of people this is named “empathic complicity”. It’s the reason for solidarity, mutual support and help. Social responsibility is programmed inside of us on the biological level. Later, a person turns this instinct into music, poetic word or a prayer. Light and beautiful April soul left this world in cold December 2013. Olena saw the beginning of Euromaidan one month before her death. Maybe it was easier for her soul, made from poetry, music and flowers, to leave this worlds seeing Ukraine as she started releasing from the hold of the Kremlin horror… I don’t know, maybe God sent the “hawks’ night” after her. But I know that she go t a “swan’s soul”. This beautiful soul left Ukraine when a countdown of new historic time started for the country, and this soul flew over Ukraine and that high pine of ours. lena’s soul bid farewell to it, while the pine kept growing, full of powers and life.

t a “swan’s soul”. This beautiful soul left Ukraine when a countdown of new historic time started for the country, and this soul flew over Ukraine and that high pine of ours. lena’s soul bid farewell to it, while the pine kept growing, full of powers and life.

Oksana Pahlyovska, writer, culture expert, professor at The Institute for Research of Social History and History of Religion (Vicenza, Italy), daughter of Ukraine’s prominent poet Lina Kostenko

“Soft and solid”

I remember Olena from the Art-Line magazine. It was in the mid- 1990s, the blessed, even if short-lived period of actual media freedom, not the one simulated by today’s Shuster-like talk shows. At that point, Ukrainian media were actually Ukrainian, both in terms of owners, and in terms of content. Ukrainian journalists did not look up to Moscow, but to the West, actually trying hard to win the audience in the good old meritocratic way – by the quality of publications. As a result, Ukraine had press that was interesting to read and TV that was interesting to watch. More than that, it was necessary to read and watch them as the only source of information about what other Ukrainians were writing, shooting, playing or painting, and how they live in general – just like in an actual European state. In a word, Art-Line edited by Yuriy Chekan was a must-read for all. So were Olena's articles. Yuriy called me once and asked me to write a small essay for them (I think it was about some international writers' forum which I had just attended) – we were faxing tests back then; we didn't have Internet. Then, we had to go to the office for our pay. The magazine's office was in some industrial middle of nowhere – in the district of Bilshovyk factory. That was where I first saw Olena Chekan in person, someone I had previously known through publications – always smart, intelligent, marked with special “internally toned-up” of style and (lost in between the lines but impossible to hide) – sincere and unimitable excitement about things (and people) she wrote about. Olena was a beautiful, similarly toned-up, and elegant woman. We exchanged several jokes and I remembered her laugh: she looked good laughing, which doesn't happen to many beautiful women (Lesya Ukrayinka was the first one to note that – her Mavka had an instant accurate impression of Kylyna from her “laugh and voice”; when Lukash told her that it wasn't enough, she said confidently that it was “perfectly enough”; laugh and voice are indeed the most certain markers of a person that never deceives anyone). Many years later, I found out that for Olena, Lesya Ukrayinka was too one of the “key writers”, the ones who stay with you “through – out life”. One important aspect that completed her portrait to me: she was a woman of that specific type, Lesya's readers. And that is an original cultural category, an elite one I would even say…The most memorable story of Olena was linked to another classic figure. Writer and journalist Yuriy Makarov shared it. He then worked with Olena at 1+1 (when the TV channel still had a wholerange of intelligent debate shows and great art programs, before it was Putinized). The idea to shoot a documentary about Taras Shevchenko, according to Makarov, was Olena's. He was the driver behind the entire project (“Yurochka, we must do it!” – I still hear her soft yet solid tone, echoed enchantedly by Makarov later, and it brings to my mind the “soft solidity” formula invented by poet Vasyl Stus and documented by Mykhailo Kheifets in his memoirs. In Olena, that was felt all the time…). Then, during the shooting of My Shevchenko documentary (it is still the best unparalelled piece amongst all the ones about Shevchenko over all years of Ukraine's independence!), in Kazakhstan, in the middle of the Kos-Aral desert that's half a day drive in a rattly old Soviet bus from any settlement, Olena was bitten by a snake on her leg. The crew had to choose, Makarov said, between leaving the shooting and rushing to the closest hospital, or finishing the shooting by the end of the light day and then leave. That would mean losing several hours that could have been crucial to Olena's health, even life (nobody knew what kind of snake it was). Hers was the final choice. Extremely pale, with her leg squeezed by a tourniquet, she was conscious enough to decide. And she said: “Keep shooting!”

They stayed and finished the shooting. Eventually, when they got to the hospital, the doctors wondered how Olena survived. The snake had actually been a venomous one. Shocked by the story, I called Olena and asked for details: she only laughed, in her beautiful manner, albeit maybe a bit more nervous than normally. She said she thought of this as a miracle, the result of Shevchenko's protection of her. She also said that she sensed this protection the entire time they worked on the film. Later, they all had to leave the TV channel. They were replaced by completely different people who started shooting completely different films. Meanwhile, the space for culture journalism where Olena had worked began to shrink rapidly since the early 2000s. Very few publications were still in Ukrainian, and even fewer offered the quality that fit Olena's publications. I don't know what one feels when the system squeezes him or her into the sidelines of profession, drives him or her into a hole like a billiard ball and all this person can do is watch helplessly indifferent cynical and semi-literate ignoramuses taking over his or her air time, pages in magazines, and number of characters. I assume Ukrainian intelligentsia experienced something similar back in the stifling 1970s: in the generation of my parents, the most widespread disease was cancer. The body was destroying itself under the pressure of long-lasting stress. I didn't follow her for a while. Then I found out that she had cancer… In terms of Ukrainian journalism, I will always remember her as a model of what that journalism had been in the brief happy time, and what it could be today. If it hadn't been for the war which we left unnoticed for 15 years. Olena was the victim of that war – nobody registered  her as that, but, without a doubt, similar to a wide range of brilliant Ukrainian journalists of the 1990s, she was simply prevented from revealing her talent to the fullest extent. It would be a great idea to publish her most interesting pieces in a separate book. For the future journalists of the new Ukraine.

her as that, but, without a doubt, similar to a wide range of brilliant Ukrainian journalists of the 1990s, she was simply prevented from revealing her talent to the fullest extent. It would be a great idea to publish her most interesting pieces in a separate book. For the future journalists of the new Ukraine.

Oksana Zabuzhko, writer and poet

“Forever”

Olena Chekan came into journalism from the theater. Her favorite activity was to recite poetry. The golden rule of journalism is to keep balance. Olena often neglected this rule and that’s why readers loved her: she was answering emotions with emotions. She didn’t just formally ask her questions during the interviews, she was talking with her heroes as if it were a private conversation. For people to interview, she always chose those she found interesting. We had multisided relations with Olena. She was my editor at the Ukrayinskiy Tyzhden (The Ukrainian Week) weekly, and a sensitive and attentive one. She was also my interviewer (we talked about radio art, wine culture and Ukraine). She was my author (she told about her favorite  music at my Above Boundaries radio show). And, finally, she was my pen-friend. I liked to receive her letters; they were always clever, witty, ironic and lyrical. I remember very well her essays about her trips; I remember her voice and her laughter. I often feel that I wish to write her a letter and then to wait for her reply. All her letters sent to me were signed by her with an English letter “F”. I was the only one who knew that this letter was for the word “forever”. And she remained for me like this – “forever”.

music at my Above Boundaries radio show). And, finally, she was my pen-friend. I liked to receive her letters; they were always clever, witty, ironic and lyrical. I remember very well her essays about her trips; I remember her voice and her laughter. I often feel that I wish to write her a letter and then to wait for her reply. All her letters sent to me were signed by her with an English letter “F”. I was the only one who knew that this letter was for the word “forever”. And she remained for me like this – “forever”.

Igor Pomerantsev, writer, poet and journalist

Video copyright ©Literaturhaus Wien